Pete Townshend’s solo album All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes was released 40 years ago!

The album was released by Atco Records on June 14, 1982, and was produced by Chris Thomas and engineered by Bill Price, who also worked on Pete’s 1980 hit album Empty Glass. The album charted at #32 in the UK, and #26 in the US.

Pete played a number of instruments on the album, including various guitars, and the Prophet, Arp 2500 and Synclavier synthesizers. He brought in outstanding studio musicians to back him up, with Tony Butler on bass, Peter Hope-Evans on harmonica, Mark Brzezicki and Simon Phillips on drums, Jody Linscott on percussion, Chris Stainton on keyboards, Virginia Astley on piano, and Poli Palmer on tuned percussion.

Pete began writing songs for the album in 1981, soon after The Who’s Face Dances tour had ended. Some of the early writing took place in New York. Demos for the album were primarily recorded at Pete’s Eel Pie Oceanic and barge studios in Twickenham. The main recording sessions were completed in April, 1982, and took place at Oceanic, AIR, and Wessex studios in London.

The period when Pete was working on Chinese Eyes was a tumultuous and transitional time for him, as it was for the whole music industry. The early 80's pop culture was moving away from the old guard of the 70’s guitar oriented rock bands in favour of the New Romantics era of synth-pop and New Wave bands that represented the modern youth. The 60’s musicians were then in their mid to late thirties, which isn’t old at all, but seemed ancient at the time in an industry that had always catered to teenagers. Music was becoming very visual, and rock videos and MTV were vital for promotion, so looking young and fashionable was important. Older artists had to update their image and sound to fit in.

Pete had a lot on his plate at the time, with contractual obligations to produce multiple solo and Who albums in between tours for The Who. He had been struggling to produce music for The Who for a few years, and wanted to write songs that better fit this new era of music and his burgeoning solo career. He found writing for the band very restrictive musically and lyrically, especially compared to the freedom he felt working on his solo material, where he could be much more experimental. The more personal songs that were on The Who’s 1981 Face Dances album would have likely worked much better on a solo album, although he was often criticized for using his best songs on his solo albums instead of giving them to The Who. His heart was no longer in The Who, and he wanted to break away as a solo act.

In addition to his recording commitments, Pete was also juggling a number of businesses for his Eel Pie company, such as a recording studio, book publishing company, sound equipment company, and the Magic Bus bookshop located in Richmond. He was spread too thin to adequately manage everything, and ran into financial problems. He had over extended himself and was in major debt. Money from his recording contract went to the banks to keep him from going under, and he ended up shutting down most of the businesses.

The pressures on Pete were immense, and his health was deteriorating quickly. His addiction to drugs and alcohol spiraled out of control, leading to the infamous drug overdose that nearly killed him at the London nightclub Club for Heroes in September 1981. This wasn’t long after Pete’s old mentor and The Who’s previous manager Kit Lambert passed away in tragic circumstances involving drugs, which must have been very upsetting for him at such a vulnerable time. Pete’s erratic behaviour and addiction problems were too much for his family to deal with, and it shattered his relationship with his wife Karen. The events going on in Pete’s life were the perfect storm that nearly led to his demise.

Fortunately, Pete recognized that he was in major trouble, and paused work on everything to get himself badly needed help. In early 1982, he received Neuro-Electric Theraphy from Dr. Meg Patterson in Corona del Mar, California to help break his addiction to drugs and alcohol. During his stay in California to go through detox and rehab, he wrote some songs for his album, and a few short stories which ended up in his semi autobiographical book of poems, Horses Neck. The treatment worked wonders, and he returned home a changed man, happily reuniting with his wife and family. He was able to complete his work on the album with a fresh outlook on life, and rewrote many of the songs with a renewed sense of vigor.

Such pressures in life can often make diamonds, and Pete came up with a few real gems for Chinese Eyes. Some of the best songs he has ever written are on this album, with some of his most personal and introspective lyrics. The Sea Refuses No River is absolutely brilliant. A heart felt cry from someone who was falling into the abyss. Exquisitely Bored has a great vibe and sounds gorgeous. Slit Skirts is a sentimental classic about mid-life crisis that has withstood the test of time. There just isn’t a bad song on this album, and knowing the background of what was going on during the production of it makes it all the more remarkable.

Pete’s vocals and instrumentation are impressive throughout. His experimentation with lyrical and vocal techniques, integrating poetry and spoken word into some of the songs, was innovative. His lush synth orchestrations, punchy guitar sounds, great melody lines and musical hooks are what makes this album outstanding. Outside of the somewhat daft title, All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes is truly an underrated classic that Pete Townshend should be very proud to have in his catalog of work.

To celebrate the anniversary, here is a look back at the history of the album, told in Pete Townshend’s own words in various interviews and writings over the years.

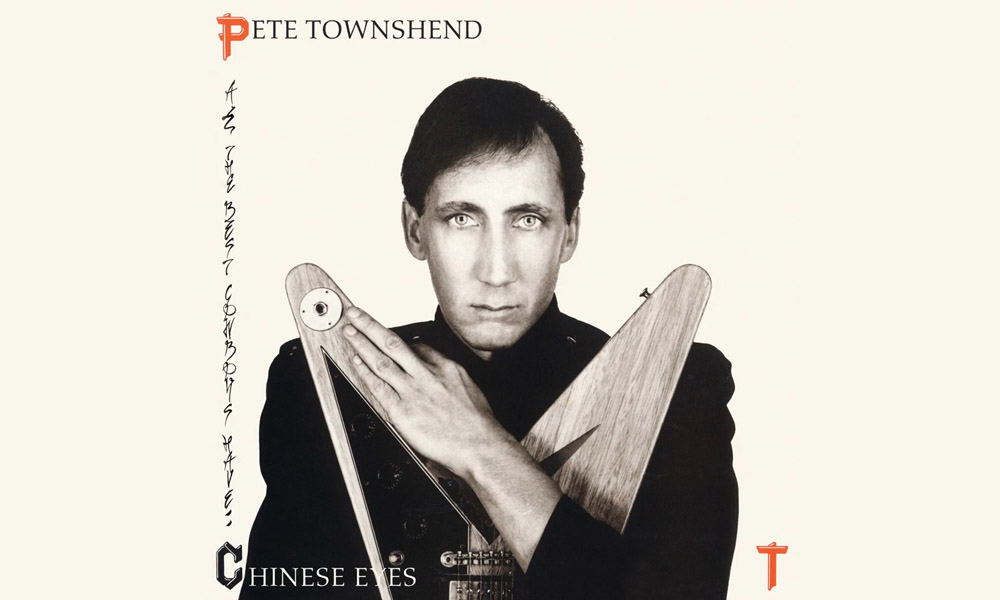

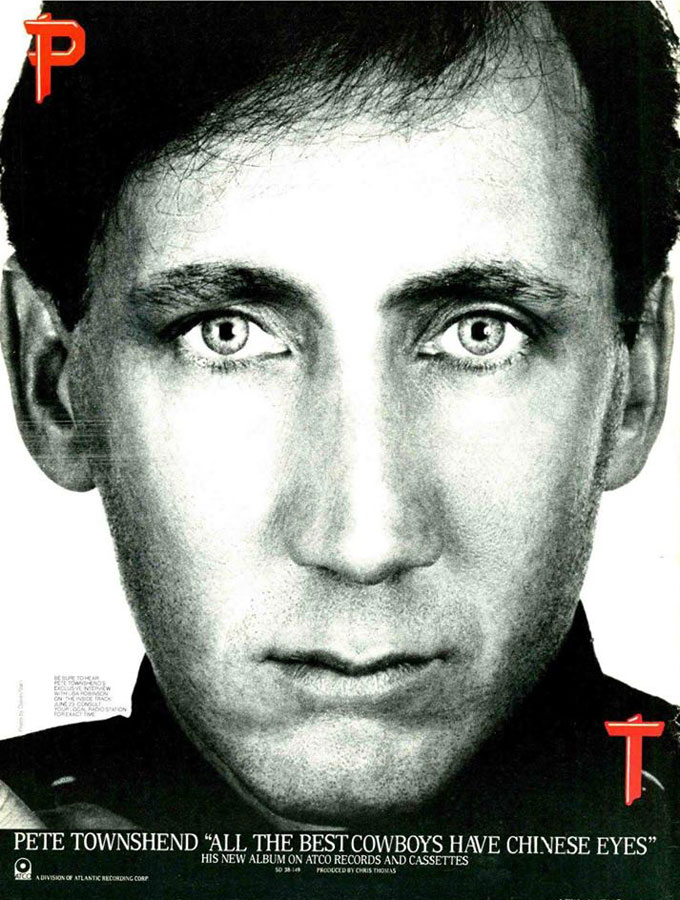

Chinese Eyes promotional poster

Chinese Eyes promotional poster

Pete Townshend narration, All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes Video EP, 1982

There are no great revelations to be made about the making of this album that I call All the Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes. There are no great revelations about the songs in it either, except one. And that’s because this is the first record that I’ve ever made during which I felt there was no hope whatsoever to try and rebuild my lost love for my wife and family, or to repair the damage I felt I had unwittingly laid on my friends and my relationship with the other guys in the band, The Who. And the songs, as a result, are each a reflection of an aspect of what it’s like to feel alone, I think. And yet still be yearning for lost emotions and power.

The cause of the loneliness is partly obvious, I had become incredibly confused over the years with The Who. I think anybody that’s read interviews that I have done over the years and seen the work of the band knows the kind of confusion, and perhaps it’s a kind of self inflicted torment. I know a lot of people reckon I could not live without it. A lot of the values that I held to be important in the early part of the bands career, and in the early 70’s, spiritually, and morally, and creatively, got let down somehow and compromised. I think because I wanted an easier and happier life. I’ve always found it difficult to say no. I think that applies also to "no" when somebody asks you for a favour, and also "no" when somebody is trying to inveigle themselves into your life in some way. I spread myself really thin in this pursuit of the good life. My wife and I lost touch, even living in the same house. And the drinking habits became downright selfish. And the business pursuits I’d got involved in outside of the music distracted me from my creative work. Almost two thirds of the way through this record I came to my senses. With a lot of help from friends I got back to my work and my family, and my wife and I began again. It’s incredible to me how music began so simply for me as a kid in Acton, and I had no idea how much it would challenge me when I got older. And how much the simple thing I call rock and roll could give, and how much it could take.

Half the time during the summer of ’81, when I was doing all the writing, I was experimenting. I knew I wasn’t near what I desired, I mean in my life, my writing. I wasn’t really happy. It’s amazing to think that somehow everything has come around full circle. I’m back with my family now, it’s the summer of 1982. And looking back at the record, listening to the record, playing the music again, songs like Slit Skirts are like the new anthems in my life. Love always wins out in the end. But when you are down it’s hard to believe that.

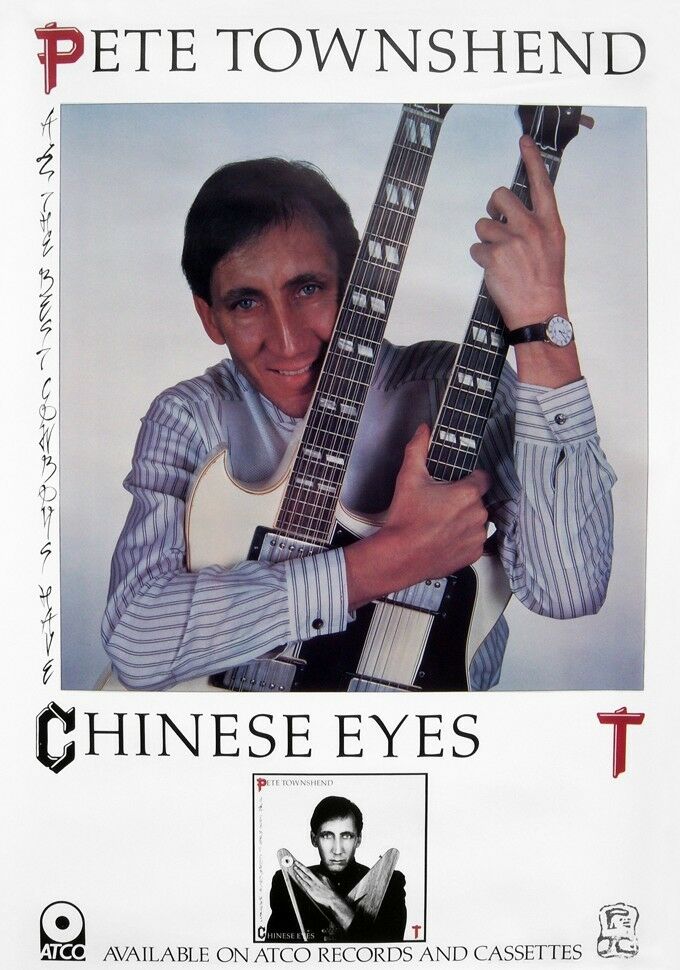

Chinese Eyes inside album photos by Chalkie Davies and Carol Starr

Chinese Eyes inside album photos by Chalkie Davies and Carol Starr

Pete Townshend interview with Vic Garbarini, Musician, August, 1982

When I started Empty Glass, I was hoping that I was going to pursue two careers at once, not realizing that they’re irrevocably knotted together. I hadn’t quite realized how much what I did as an individual would affect the Who, and vice versa. [Chinese Eyes] was a big difference, in the approach to it and with the ruthlessness with which I had to deal with the Who, with everything around me, in order to get it made. It’s actually a recognition of that essence of commitment, a commitment to a set of principles which I’ve debated over the last ten years: the importance of a family, the importance of my role with my peers and the band, the importance of my freedom of self-expression, and lastly but not at all least, the importance of becoming actively immersed again, for only the second time in my life (and the last time was when I was seventeen) in politics. I really do feel that I can’t sit and watch any longer. There’s a kind of selfishness in people who sit back and watch when they have a unique position to get respect and attention. I just think it’s too good an opportunity to say something I feel is in everybody’s bones.

Pete Townshend interview with Paul Du Noyer, NME, June 12, 1982

[After The Who’s Face Dances album], I started thinking practically immediately about a solo album, because I was really frustrated with The Who album. It didn't seem to do anything or go anywhere, and I couldn't quite work out why… So my first reaction was just to run like shit from The Who because they were confusing me more than ever. And I started producing material for my own record, and I went to New York and Paris and a few other places, just to change my environment. I was going to form a band.

Pete Townshend interview, Inside Track, 1982

[Chinese Eyes is] more of a continuation on from Empty Glass than from Face Dances the Who album was. Well I’ve now decided that there’s one kind of writing for the band, and one kind of writing for me. With the band, there’s more writing to a brief. There’s more writing, bearing in mind that I am writing what other people in the group have got to stand by and feel good about. When I’m writing for myself, I can just afford to get into more of a consciousness stream. Allow whatever comes out to stand for whatever it is. I find writing for the band to be most difficult. It’s the easiest thing in the world to just sit and scribble.

Pete Townshend interview with Kurt Loder, Rolling Stone, June 24, 1982

I think the album is fairly cathartic in some ways. The writing ranged over the last two years, which have been very, very peculiar for me, ’cause I’ve been through a lot of really weird things. I went through the normal, continuing heart-searchin’ over the Who, and I lived away from my family for quite a long time as well; we have a house in the country, and I was living there, mainly. I made a lot of deliberate pleasure trips to New York and L.A. I spent some time in Paris, a lot of time in the country working on a book of short stories and other times just knockin’ about with some of the London club-scene people. I enjoy a lot of that life, in a way. But all the time, behind the scenes, I was writing songs and recording in fairly long spurts.

Pete Townshend interview, October 2005 (published in petetownshend.com Diaries, 2006)

By this time several things were clear: my marriage was over (though I managed to revive it for a long period some time later); the Who were heading for a fall; I could never drink or use any kind of drugs again. I didn’t really feel the need to apologise or confess, but I did need to share what had happened because it simply wasn’t obvious. While my personal life fell apart The Who filled Wembley Stadium for the first time for a single rock band. I was very angry about everything, and kept it fairly bottled up. I enjoyed working on Chinese Eyes. I feel it was an honest album, and more courageous creatively. With this record though my relationship with Atco changed, I felt they disliked the record, and from there onwards we operated at arm’s length.

Pete Townshend Somebody Saved Me, Amazon Audible, May 2022

With respect to Chinese Eyes, that was an album where, for me, I just decided that, in a sense, all bets are off. Let’s just do what falls under the fingers. And that’s what happened.

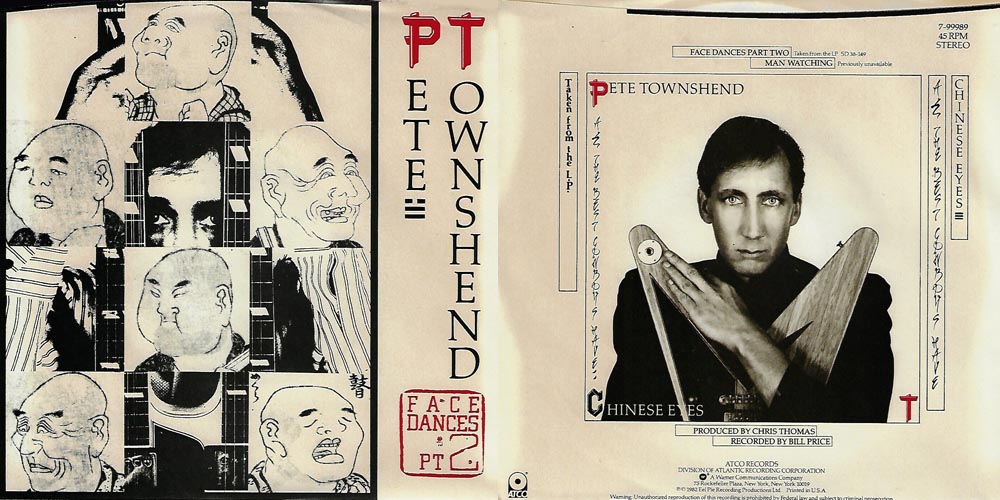

Chinese Eyes promotional poster

Chinese Eyes promotional poster

Pete Townshend Somebody Saved Me, Amazon Audible, May 2022

The Chinese Eyes album demos were recorded [at Pete’s Meher Baba Oceanic] in the room in which we had all these celebrations, celebrating the life, the work, and the films of Meher Baba. And it felt the right place for me to be going through that deconstruction creatively and artistically. But it was poignant and it was sad, there was a sadness to it. And I think that you can feel that in the record.

Pete Townshend interview, Inside Track, 1982

Chinese Eyes started off with a very aggressive experimentation. Originally there was going to be a lot of poetry on it. That’s what I was experimenting on when I was in New York. I had done a lot of experiments with echo effects on percussion. But in a sense what happened was those early experiments, they were all quite satisfactory and interesting, but it always comes back down to the song. Whether or not the song has got any real guts and any real need to express itself.

Pete Townshend interview with Paul Du Noyer, NME, June 12, 1982

I was keen not to end up with a heavyweight record, to get away from people’s preconceptions. So it started off very experimental. When I took the first tracks to New York and played them to the record company – you would have paid money to have seen their faces! I mean, they were just watching millions of dollars disappearing in front of them. Cos my last album sold incredibly well in America. I was determined not to be caught up in the commercial machine. I thought, fuck it, do what I wanna do. And in the end I realised that what I really wanted to do was sell records!

Pete Townshend interview, Inside Track, 1982

Once I started recording for real, with Chris Thomas, I started to write in a slightly more formal manner. What I did, which was slightly different from the last album, was to put a groove together. I used the same group throughout the record. When we started into rehearsals, we did two weeks rehearsals before the album started, I started to realize that this format had a kind of potential in itself.

Pete Townshend autobiography, Who I Am, 2012

[In June 1981] the Oceanic sessions for my second solo album began in earnest, recorded by The Who’s soundman Bob Pridden. I’d decided I wanted to record all the tracks live, so the band gathered in the studio where we could all hear each other. I was playing my old Telecaster through a Fender twin amp, Tony Butler and Mark Brzezicki from my brother Simon’s band were the rhythm section, Jody Linscott was on percussion, and Peter Hope-Evans on the harmonica and Jew’s harp. For these first sessions Chris Stainton, who played with Joe Cocker and Eric Clapton, was on piano and Hammond, while Polly Palmer (from Family) played tuned percussion – glockenspiel, marimbas and vibraphones. In one week we rehearsed Face Dances, It’s In You, Stop Hurting People, Dance It Away, Man Watching, Sean’s Boogie, The Sea Refuses No River, and Communication. The sound was epic.

Pete Townshend interview with Paul Du Noyer, NME, June 12, 1982

Well, I didn’t have to look very far for [Virginia Astley, who plays piano on the album], cos she’s my sister-in-law. I know it was very fashionable last year – and I don’t mean this to demean all the genuine female talent – but there was a fashion for rowing a woman in, row in a couple of birds. Do I dare say this, The Human League, they did it, didn’t they? It looked like a row-in to me – a very delightful one, which might develop into something substantial. Anyway at that particular time I decided that I wanted a band of women. And that was basically because I was fed up with men. I really was. I was fed up with male sensibilities. I was fed up with fighting for everything I wanted, sometimes physically fighting. I was fed up with the macho music press. And I was under the misapprehension that maybe if I surrounded myself with female players that a lot of that would recede. I think perhaps now that I was just hoping that I'd be able to get what I wanted more quickly.

Chinese Eyes magazine ad

Chinese Eyes magazine ad

Pete Townshend interview with Kurt Loder, Rolling Stone, June 24, 1982

Basically, [the title All the Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes] is about the fact that you can’t hide what you’re really like. I just had this image of the average American hero – somebody like a Clint Eastwood or a John Wayne. Somebody with eyes like slits, who was basically capable of anything – you know, any kind of murderous act or whatever to get what was required – to get, let’s say, his people to safety. And yet, to those people he’s saving, he’s a great hero, a knight in shining armor – forget the fact that he cut off fifty people’s heads to get them home safely. Then I thought about the Russians and the Chinese and the Arab communities and the South Americans; you’ve got these different ethnic groups, and each has this central image of every other political or national faction as being, in some way, the evil ones. And I’ve taken this a little bit further – because I spent so much of my time in society, high society, last year – comment on stardom and power and drug use and decadence, and how there’s a strange parallel, in a way, between the misuse of power and responsibility by inept politicians and the misuse of power and responsibility by people who are heroes. If you’re really a good person, you can’t hide it by acting bad; and if you’re a bad person, you can’t hide it by acting good. Also – more to the point, really – that there’s no outward, identifiable evil, you know? People spend most of their time looking for evil and identifying evil outside themselves. But the potential for evil is inside you.

Pete Townshend interview with Paul Du Noyer, NME, June 12, 1982

I was struck by a feeling last year that, particularly viewed from California, that stardom as they saw it, establishment stardom, and drugs and decadence, AND the world’s power structure, all somehow had this thread going through them. And what it was was people’s need to externalise – er, this gonna sound like Pseud’s Corner – to externalise evil, and even power. In other words, to say, there’s fuck-all I can do about it, it’s them. It’s the Chinese, fuck-all I can do. It’s the Japs, or it’s Ronald Reagan, or it’s Margaret Thatcher. Nothing we can do. It’s the police, they’re fascists. And, in a sense, people’s need for people like me – either to build up or to crucify, or Strummer or Weller or anybody else who’s gone through a similar degree of external examination, and self-examination. The need for that is, I think, the fundamental weakness we’re suffering from at the moment, in that we’ve become so media-ised, so used to externalising everything, that we don’t take responsibility for fucking anything. And that’s really what the title’s about: the heroes and villains all look the same, they’re all ‘over there’, they’ve all got slit eyes. I’ve tried to explain it in the story on the cover, but it’s very hard. I didn’t want to explain it and make it all too pat, cos I see it on a thousand different levels.

Pete Townshend interview with Paul Du Noyer, NME, June 12, 1982

[Dedicating the album to “Meg and to other teenagers in love everywhere”] was a last minute thing. Well, it’s dedicated to Meg Patterson, cos she got me off junk. And then to my wife and myself, who are behaving like teenagers at the moment. I didn’t think I could dedicate the album to The Sex Pistols again. (Laughs)

Songs

Stop Hurting People

The Sea Refuses No River

Prelude

Face Dances Part Two

Exquisitely Bored

Stardom in Acton

Uniforms (Corp d'esprit)

North Country Girl

Somebody Saved Me

Slit Skirts

Stop Hurting People

Pete Townshend interview, 1982

I wrote it last summer. I suddenly broke down and scribbled it out on a piece of paper, and didn't realise until later quite to what an extent it was a prayer.

The Sea Refuses No River

Pete Townshend narration, All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes Video EP, 1982

The river is always attracting me. For the last 15 years I’ve lived by the river Thames. Reading a book like Wind and the Willows, I often identify with Mole, the hero, who is drawn to the river for the first time and meets Rat, who he shacks up with in his little riverside shack. And Rat introduces Mole to all the rivers charms, and all the dangers too. This river, the Thames, flows constantly on. It always reminds me of a soul irrevocably plodding on towards God. It’s full of food for fish, and it provides London with most of it’s water. And yet it’s also treated like a rubbish dump by a lot of people. They chuck cars in and their beer cans and everything else. And many rivers still get used as sewers. And yet they all get to the sea in the end. So the analogy with the human soul always appeals to me. The fact that, it doesn’t matter how clean or dirty you are, you get there in the end. It reminds me constantly, the river, of my immortality and of my goal. And in a strange way, however I feel, it reminds me of my permanence. I can’t really explain what happens when I write songs. On the album, in The Sea Refuses No River, I actually directly use the river analogy. Sometimes it comes through more mysteriously. I think writing is a mysterious process until you look back on it. And then like a clever critic, you can see clearly where you went wrong or where you succeeded.

Pete Townshend liner notes, The Best of Pete Townshend, 1996

I think somebody described The Sea Refuses No River as a suicide note. In actual fact, what it is is a song of acceptance. This is another one of those songs that grew out of my interest, not just in Meher Baba, but also in the poets that Meher Baba enjoyed when he was a young man in his thirties. His interest in this poetry led me to go and look at it. He was often quoting bits of it, but I went to examine it, and I was very struck by the use of wine as an analogy for God’s love, and therefore by association that the tavern is the heart. The tavern is the place where you receive God’s wine, and what you have to do is you have to hold up an empty cup – which is where I got the title of my first album – in order to receive. Anyway, this song is about all of the different qualities of love, and I remember once Meher Baba freely interpreting a poem about the fact that if God’s love is wine, then human love is like water, and lust is like the stuff that runs into the sewer, but that in the end it all combines in this huge ocean which is the infinite presence of God, and therefore it’s all subsumed and mixed and one. And that’s what the song is about.

Pete Townshend Somebody Saved Me, Amazon Audible, May 2022

I don’t know that [Chinese Eyes is] entirely autobiographical. I think that if you took a song like The Sea Refuses No River, it would be autobiographical in that I had always regarded myself as being on a spiritual journey. I had got into Meher Baba in 1967, this was before Tommy and before that hippy era. The Sea Refuses No River is… I’ve explained the connection with Meher Baba and with Rumi, the idea of the soul dropping into the ocean. It’s a rip off from Persian poetry really. The fun thing about this is the simplest opening of any song I’ve ever written.

Pete Townshend interview, Inside Track, 1982

I wrote two songs especially for this band lineup. One was called The Sea refuses No River and the other was called Slit Skirts. In fact Sea Refuses No River has come out sounding a little bit Bruce Springsteen. It’s got a glockenspiel on it, which he uses a lot. It’s because of the percussionist I’ve got in there, it was just being used.

Prelude

Pete Townshend narration, All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes Video EP, 1982

Prelude, is a simple prayer for change in a world that from my viewpoint had gone crazily wrong.

Face Dances Part Two

Face Dances, Part Two (B side Man Watching) was released as a single on May 21, 1982, which failed to chart despite the video getting extensive play on MTV.

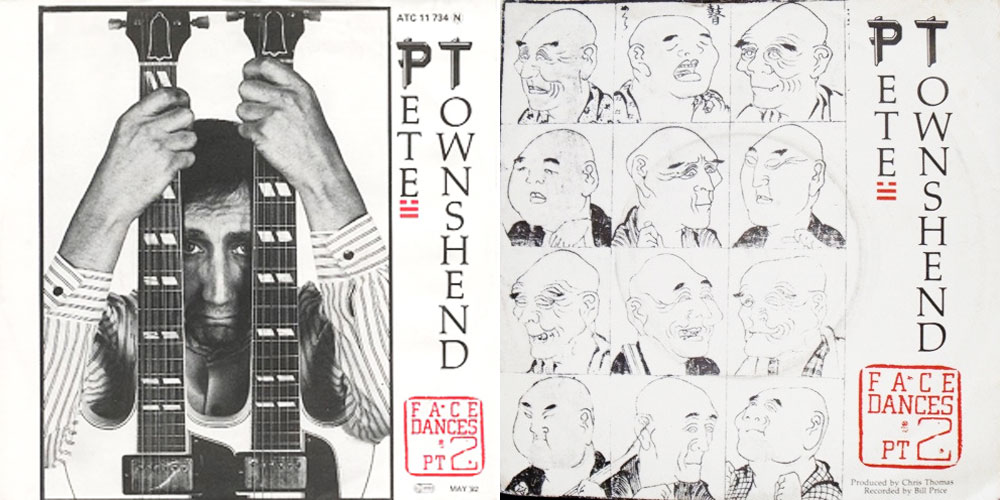

Face Dances Part 2 singles artwork

Face Dances Part 2 singles artwork

Pete Townshend narration, Chinese Eyes video documentary, 1982

Face Dances is the anthem of the soul in solitary confinement, this feeling like feeling in jail. And the face that I sing about is my own. I wrote the words while I was looking in a mirror.

Pete Townshend song introduction, Pete Listening Time, 1982

The single from this album has a quite confusing title. It’s called Face Dances Part 2, and has absolutely nothing to do with The Who’s last album at all. It’s just a coincidence.

Exquisitely Bored

Pete Townshend song introduction, Pete Listening Time, 1982

California. I was over there taking a break earlier this year in January, and although California is supposed to be the Garden of Eden and all that, every time I’ve ever spent any time there it’s always been pissing down with rain. And it was this time. But nonetheless there was still the same air of ‘ennui’ as Holmes used to say “I’m suffering from ennui Watson”. It’s another word for boredom. But it’s a very pleasant boredom that you endure in California. I popped up to see Joe Walsh when I was there and asked him what the Eagles were doing. He said “We’re not doing anything Man” (laughs). And it inspired this song that I wrote in the Tom Waits tradition while I was over there.

Communication

Pete Townshend song introduction, Pete Listening Time, 1982

This track is one of the most experimental tracks on the record. I tried all kinds of things on this. Took the word ‘communication’ and broke it up into little bits.

Pete Townshend interview, Inside Track, 1982

Communication is about people pretending to communicate when they're not. I’m using very flowery, what I call lyrical prose. Instead of just saying whatever it is they want to say. Hiding behind their words. So I took the word communication, which should really speak for itself, and broke it up into bits, so it turns into the word “come” quite nicely. Come, come, come, come… and it turns into commy, commy, commy, commy. And things like that. I just broke the word up, and then followed it with a bit of absolutely dire schoolboy poetry. Things like briolette tears, and frozen masks, and backs of whale, and icebergs on frozen seas, and all that stuff. Just to demonstrate that there are really two ways of killing the cat. It’s just a song about the need to really say and to speak and to talk about. I hope that the song gets across that mood, through the urgency of the music behind it. It’s a good track.

Pete Townshend interview with Vic Garbarini, Musician, August, 1982

On the song Communication, for example, I deliberately take the word communication and break it up into bits. I mean I literally hurl the letters of the word at the listener. And then I show a literal example of how not to communicate, which I do with flowery, meaningless prose. You know, “briolette tears drip from frozen masks, the back of the whale cracks through the ice flow,” blahblahblahblah – who needs it?

Stardom in Acton

Pete Townshend song introduction, Pete Listening Time, 1982

This track was also written in California earlier this year. This is about the other side of California. LA, Hollywood, fast cars, and everything else.

Uniforms (Corp d'esprit)

Uniforms (B side Dance It Away) was released on July 30, 1982, and charted at #48. Dance It Away, Man Watching and Vivienne were included as bonus tracks on the 2006 CD of Chinese Eyes released on HIP-O Records.

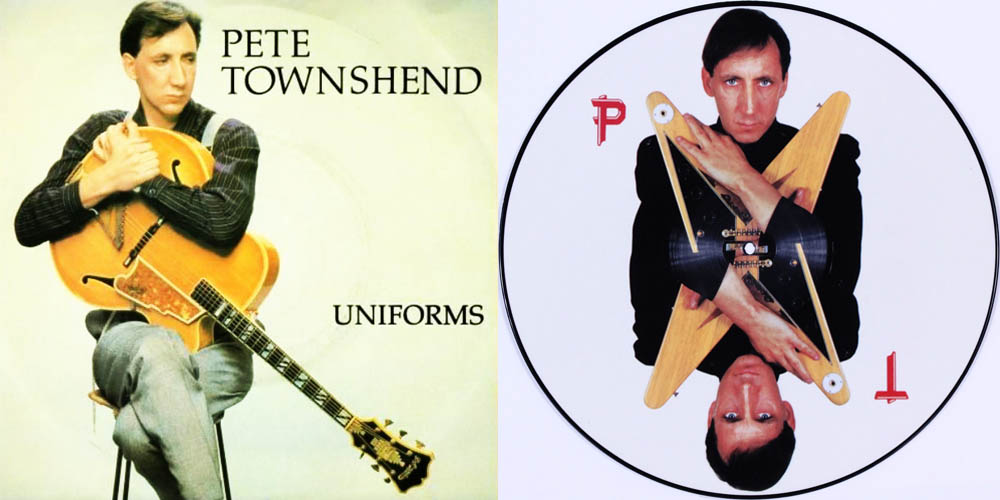

Uniforms single artwork and picture discs

Uniforms single artwork and picture discs

Pete Townshend song introduction, Pete Listening Time, 1982

The world is not in a wonderful state at the moment, it’s difficult to add levity to what is quite a serious problem in this country at the moment. It’s a reflection of what’s happening in the world. This song I wrote last year, it’s called Uniforms, and it’s not meant to be about military uniforms, it’s meant to be about every other kind of uniform that we see in this country. But it makes you think.

Pete Townshend interview with Paul Du Noyer, NME, June 12, 1982

I really like that song. I wanted to put it out as a single, in time for the Falklands crisis. I think if I see Margaret Thatcher on the TV again, talking about "our wonderful boys", with her smarmy voice, I am actually gonna be physically sick. But the song doesn't actually criticise anybody that wants to wear a uniform, it just observes it. I've always been fascinated by people's needs for that, and my need for it, and the way it's inherently wrapped up in rock music culture. Cos even in America – they think we're very cute with our weekly changes of haircut – their uniform has been identical for the last 15 years. What they think you have to wear to a rock concert, I think it's hilarious. It's that uniform you'd wear to ride around in a pick-up truck, and shout. That's the way you spend your weekend in California, you get a bottle of beer and you drive past going, Yeurgghh-uh-uh! Jesus Christ, what a way to spend your childhood. Also the reference to coke, which I think is not so much a drug problem as a problem of uniform. It's something people do because they think they should do it. The compartmentalising – of people's clothes, of the way they look, into cults, and ideologies, into actual frames of consciousness and social sensibility – is what I find amazing. I know it's often said that just because somebody dresses like a skinhead, doesn't mean they’re gonna kick you soon as they get a chance. But it does start to affect the way they think. A lot of Oi-boys start off fairly innocuously, just interested in the look, and they end up believing that they hate all Pakistanis. And in the same way, thinking back to the days of mods and rockers, mods really thought that they hated rockers. And this is the problem. And I still find it fascinating, in a dark way: why it is people do it; why the individual is not more important. And is America different? Of course over there they've got this thing about the individual, haven't they?

Pete Townshend interview, Inside Track, 1982

I don’t quite understand [uniforms]. I like it in a sense, because I think a lot of fashion has a lot to do with uniforms, and I love fashion and I like the changing moods that it reflects. I think it’s really weird in the country, for example, just prior to this war like period that we are going through, that I hope doesn’t turn into anything like war, but which might do, this Argentinean thing, that there is a fashion at the moment for battle dress and things like that. I mean severe battle dress, not just uniforms, but people dressing up like commandos. I just find it interesting. But I think there are other kinds of uniforms too. I think there’s a cocaine uniform, lets face it. People doing cocaine is a uniform.

North Country Girl

Pete Townshend song introduction, Pete Listening Time, 1982

This one called North Country Girl, which is often called Girl from the North Country, is a song I first heard performed by Bob Dylan back in ’64 I think. And since then there’s been a great version done by Roy Harper on an album of his called Valentine. But I’ve always wanted to do this song. And the deliberate mistake at the end of this record – I changed the lyric – is the word fallout.

Pete changed the arrangement of North Country Girl to a more traditional version in later performances of it.

Somebody Saved Me

Pete Townshend song introduction, Pete Listening Time, 1982

This song on Chinese Eyes is a track I wrote quite a long time ago, almost two years ago, and I included it on this record. It’s a strange song. It really is, in a way, the most autobiographical thing I’ve ever done. It’s really about how good things can happen to people, and sometimes those things can be too good.

Pete Townshend interview, Inside Track, 1982

Somebody Saved Me is really about… in Britain they call it being born under a lucky sign. I have got away with murder (laughs). It just talks about a few occasions when… in principle, one of the verses of the song is about how when I was at art school – cause I met my wife at art school but I didn’t go out with her at art school – I had an absolute fixation, obsession with another girl there. And she was unavailable and going out with a jazz musician. There was a period when they had a row. And suddenly, she was available. She made this big sort of play, “I’m available! I’m available” kind of thing. But I was so naive, and spent so much time locked away with my guitar, I didn’t recognize these signs at all. I wondered what the hell was going on. And I missed my chance. She was trying to find somebody that she could use to hurt her old man. Luckily, she found somebody else. And when she hurt her old man, she went back to her old man again, leaving this poor dude behind, who had fallen desperately in love with this girl. And I just thought how lucky it was that I hadn’t, as my first major affair, got caught up with this girl who I was absolutely potty in love with. And then she’d sort of discard me, because I would have killed myself. I’m pretty sure of that. In fact, my best friend actually did try and kill himself at art college over something similar, luckily unsuccessful. It’s about things like that. How sometimes what you think is sometimes a bad thing can sometimes be a good thing. The kick is somebody saved me from a fate worse than heaven.

Slit Skirts

The video for Slit Skirts was heavily played on MTV, but was never released as a single. Pete never did a solo tour to help promote the album, but did perform Slit Skirts at a solo performance at the Princes Trust Gala benefit at the Dominion Theatre in London soon after the album was released, on July 21, 1982. A video of the performance was played on MTV.

Pete Townshend song introduction, Pete Listening Time, 1982

Slit Skirts is a song really about, I’m 37 years old now and I’ve been in the rock business for a long time, about what it’s like to be middle aged and getting older, irrevocably and inevitably getting older, in a world of music that is changing all around us all the time.

Pete Townshend liner notes, The Best of Pete Townshend, 1996

Slit Skirts is about getting to that place in middle age where you really feel that life is never going to be the same – you’re never going to fall in love again, it’s never going to be quite like it was – and it’s a song about getting drunk, about being maudlin and sentimental, and looking back, and, as always, the irony of the intention was lost on most people. I got very, very upset when people said, “This sounds like a song that Pete Townshend wrote when he was getting drunk,” (laughs) and I’d very carefully stayed sober in order to write it, so that I could get drunk to listen to it. It evokes that feeling that sometimes I have at my age, which is that one minute I’m sitting there looking at some old crap on the TV thinking, “If I was just ten years younger, I’d probably be in a nightclub right now,” and suddenly you get to the end of the song, and you go from that reflective pseudo-tragic piano motif to the “Slit skirts, slit skirts, we’re rocking out now – more champagne!” The futility of it, the bathos of it, and it’s not unlike how I was living, when I was working on the record.

Pete Townshend interview with Vic Garbarini, Musician, August, 1982

There are two songs, The Sea Refuses No River, and Slit Skirts, where I’ve actually taken Bruce Springsteen’s writing form and demonstrated another facet of it. And on Slit Skirts I attempted – it wasn’t a hundred percent successful – but I attempted to actually break that form down, to smash at it. One thing I really enjoy about solo albums is that I can afford to be as academic as I like.

Promo Material

To promote the album, a 30 minute video was produced, which was directed by Chalkie Davies and Carol Starr, and aired September 19, 1982 on MTV. The video was filmed around Pete’s country home in Goring, his Oceanic studios in Twickenham, and in his home town of Acton. It was later released as a Video EP on VHS and Beta tape, but never came out on DVD or Blu-ray. MTV also aired edited promotional clips from the Video EP for the songs Face Dances, Communication, Stardom in Acton, Exquisitely Bored, Slit Skirts and Uniforms.

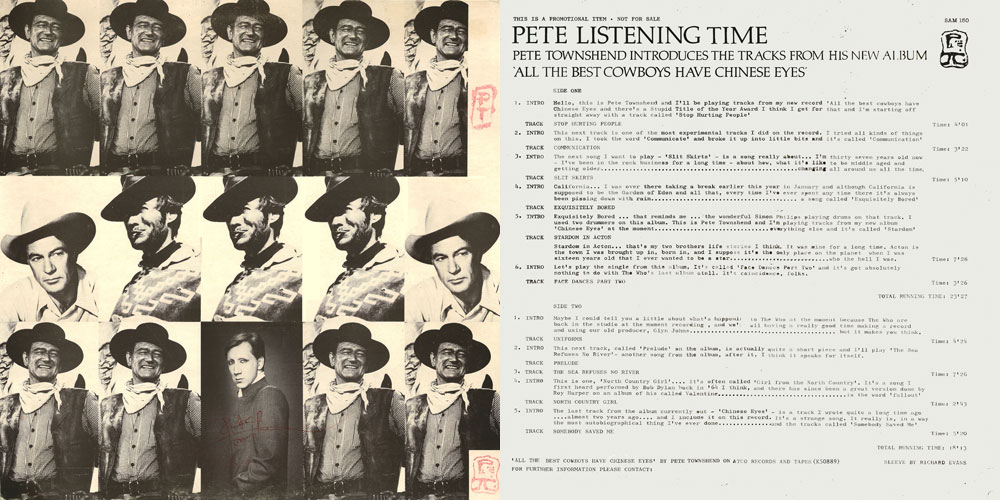

A promotional LP called Pete Listening Time was also released to radio stations in the UK, that included introductions from Pete for all the songs.

Pete Listening Time promo LP artwork and liner notes

Pete Listening Time promo LP artwork and liner notes

Produced, researched and written by Carrie Pratt.