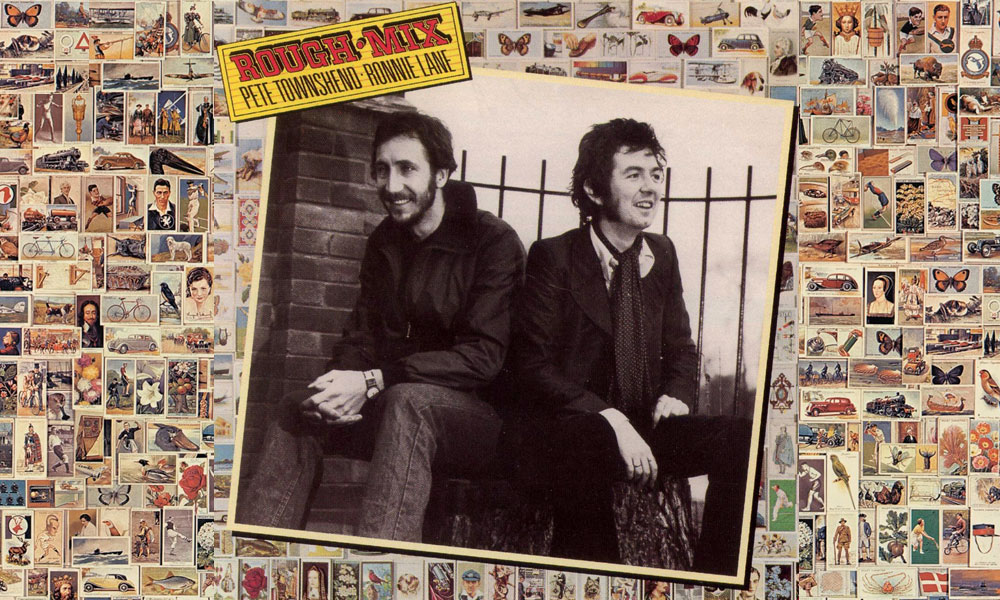

Pete Townshend and Ronnie Lane’s album Rough Mix was released 45 years ago!

The album was released in the US on September 5, 1977 by MCA Records, and in the UK on September 16 by Polydor Records. It charted in both countries, reaching a respectable #45 in the US and #44 in the UK.

Rough Mix was an extraordinary project that brought two incredible songwriters together through their bond of friendship that began in the early 60’s, when The Who and Small Faces were the biggest mod bands in London. Pete and Ronnie lived in the same neighborhood, and knew each others families socially. They shared a mutual love of Meher Baba, and had worked together before, when Ronnie contributed songs to Pete’s first solo album Who Came First and the Meher Baba albums Pete produced in the early 70’s.

Pete Townshend had never collaborated with other song writers before, and he didn’t really on this album either. Rough Mix contained tracks that were written independently by Pete and Ronnie, with musical contributions to each other’s songs that lifted the recordings to the next level. The project gave them both the opportunity to explore new styles of writing and instrumentation outside of the work they had been doing for The Who and Faces. It also relieved the extreme pressure they both faced with delivering songs for such huge entities, allowing them to be a bit more creative and less targeted to the big rock machine. The result is an amazing set of songs that contains some of the best writing of their careers. The overall vibe of the album was more British folk than rock, which was similar to the style of music Ronnie Lane was doing with his band Slim Chance.

The idea of working on an album together came about in 1976, when Ronnie asked Pete if he could produce an album for him. Ronnie was having financial issues and needed help with his solo work, which he had been struggling with since the Faces had broken up in 1975. Pete didn’t want to produce an album, but suggested they do an album together instead, and asked Glyn Johns to produce, who happily agreed.

The first recording sessions took place in September 1976, when the demos were produced using Ronnie’s mobile studio during a break in The Who By Numbers tour. During this time, Pete and Ronnie went to see their friend Eric Clapton join Don Williams for a few tunes at the London Hammersmith Odeon. Don's performance of Till The Rivers All Run Dry inspired them to record that song for the album, as they thought it would be something Meher Baba would love. They included in the liner notes, “This song is dedicated to the Old Man.”

After The Who’s tour ended in October, Pete had time to focus on Rough Mix. Recording sessions began in November 1976 at Olympic Studios in Barnes, London, with Glyn Johns at the helm as producer and engineer, and Pete’s brother-in-law Jon Astley as assistant engineer. The project’s working title was April Fools. Since Olympic was close to Pete and Ronnie’s neighborhoods in Twickenham and Richmond, it was an easy place for them to congregate. Sessions took place over the next few months, wrapping up in early summer 1977.

Pete and Ronnie played an assortment of instruments on the album. According to the liner notes, “Ron and Pete play various acoustic and electric guitars, mandolins and bass guitars, banjos, ukuleles and very involved mind games.” While they played on each others songs, the only songs they sang on together were Heart To Hang Onto and Till The Rivers All Run Dry.

They invited a few guest musicians to record at the sessions, including Eric Clapton, Charlie Watts, Ian Stewart, John Entwistle, Peter Hope Evans, Henry Spinetti, Boz Burrel, John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick, Billy Nicholls, and members of Slim Chance. It was during these sessions that Pete first met Rabbit, who went on to be the keyboard player for The Who for many years, and worked on some of Pete’s solo projects.

Pete also worked with an orchestra for the first time, bringing in his father-in-law, famous TV and film composer Edwin Astley, to arrange the orchestration for his innovative song Street In The City. Pete's storytelling of a scene in London, combined with the evocative instrumentation, created a cinematic piece of music that was ground breaking for the time.

During the recording sessions, Ronnie Lane was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis, a disease that would eventually take his life in 1997. Ronnie’s failing health was somewhat apparent when Pete and Ronnie made an appearance on the British music show, The Old Grey Whistle Test on September 26, 1977. The two were interviewed by Bob Harris and a video for the song Rough Mix featuring footage from a silent film was played, although that song was never released as a single.

Singles were released for My Baby Gives It Away (B side April Fool) and Keep Me Turning (B side Nowhere To Run) in the US, and Street In The City (B side Annie) in the UK. None of the tracks charted. The real gem on the album, Heart To Hang Onto, was never released as a single.

In 2006, Hip-O Records released a deluxe edition CD of Rough Mix that contained unreleased outtakes from the sessions; Only You and Silly Little Man by Ronnie Lane, and the instrumental Good Question by Pete Townshend. Also included was a bonus DVD that contained video interviews with Pete, Glyn Johns, and Ronnie’s former manager Russ Shlagbaum, and a 5.1 surround mix and stereo remaster of the album.

Rough Mix stands out as a truly underrated classic in Pete and Ronnie’s catalog of work. Both artists songwriting and musical efforts are top notch throughout, and their songs intermingle with each other beautifully. The alchemy of their styles and personalities blend perfectly, creating a sensational combination of music that makes this album a real fan favorite.

To celebrate the anniversary of Rough Mix, here is the history of the album told in Pete Townshend’s own words, sourced from various interviews and writings.

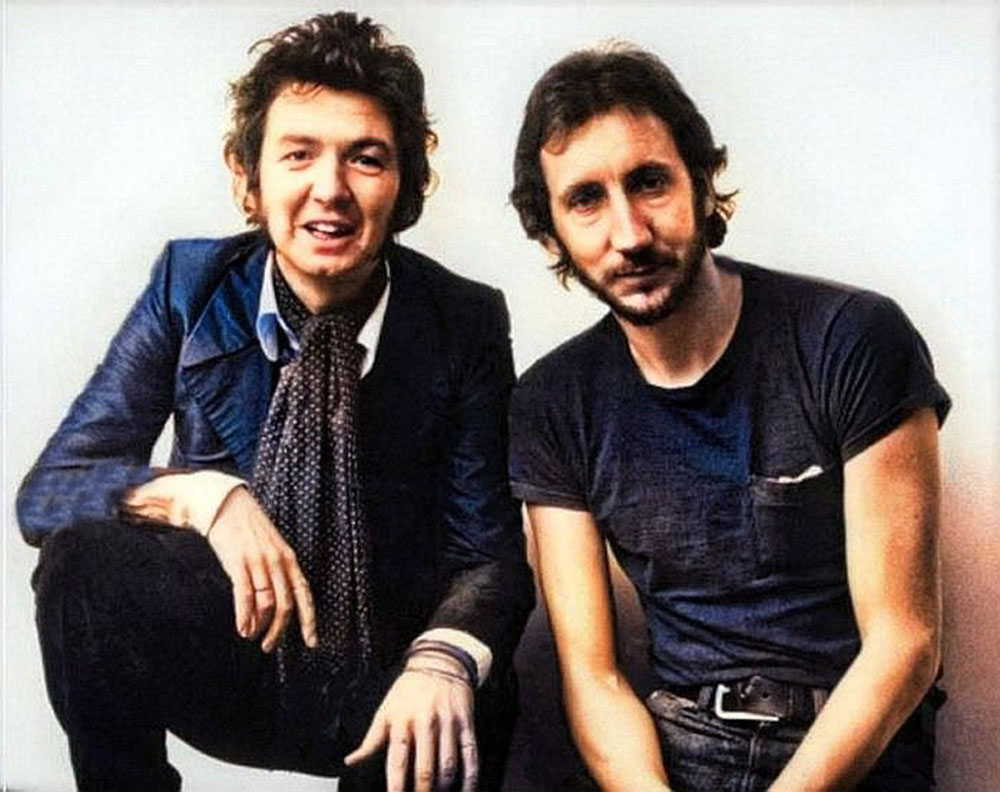

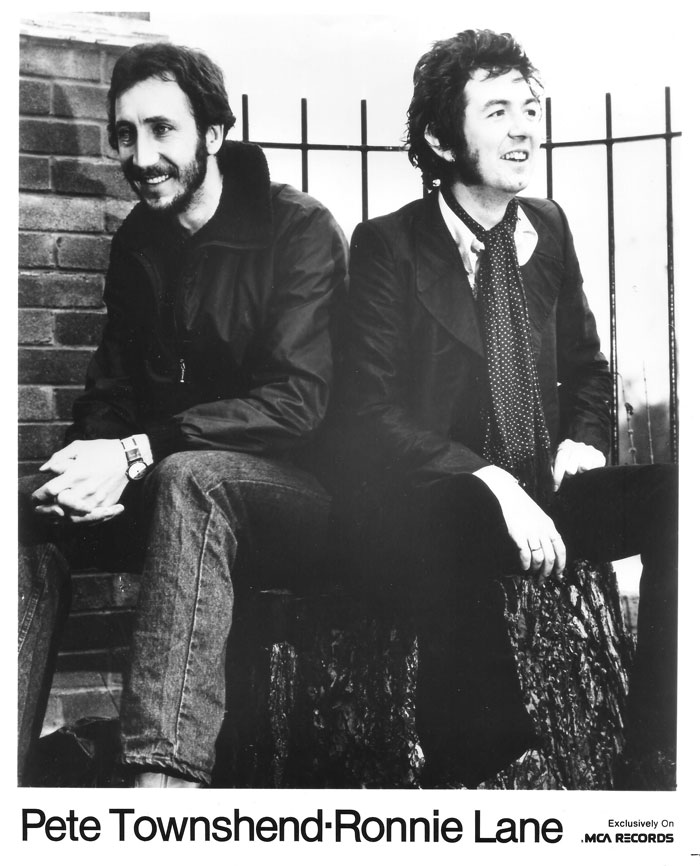

Promotional photo credit: Martin Cook

Promotional photo credit: Martin Cook

Pete Townshend Press Release Interview, September 1977

This album came about when Ronnie Lane came to see me about the rent. He had put in a bit of work with the reformed Small Faces and it had worn him out. He thought he’d like an easier life and came to see me. Actually he wanted me to produce an album for him. I’m not at all into producing people, but was keen to do something with Ronnie as I knew he would stir me up from my veritable complacency. We went to see Glyn Johns who told us that he was dog tired, overworked and although he was pleased to see us could we kindly get out of the studio while he mixed the album he was trying to finish. Before we left we asked him if he’d like (what a ridiculous concept!) to work on our joint album and he foolishly agreed.

Pete Townshend radio interview with Jim Ladd, A Rough Mix Indeed, KMET Los Angeles, 1977

Well the idea to do the album with Ronnie in the first place came from Ronnie. Ronnie came to see me. He’d just been working with the Small Faces revitalization program, and they were planning a big comeback. Ronnie was one of the original members with Steve Marriot and Kenney and Mac, and they were planning an album and tour, and stuff like that. I think Ronnie became incredibly disoriented, because I think he’d imagined at the beginning that it was just going to be a reunion concert or two, and maybe make an album. Because they had some success with an old track of theirs, Itchycoo Park had got in the charts. He came to see me with a bit of a sad story how he’d gotten in too deep and he didn’t know quite what to do. He was very worried about not doing the thing with the Faces because he felt financially he really had to, because he felt it would help his chances with his own albums in the States, which believe it or not, I think a couple of his own albums weren’t even released in America. I think Ronnie’s particular style, obviously I’ve always liked it as a friend, but it’s very varied and it’s very down-home in a way. But I really felt that Ronnie’s work needed an opening. Ronnie’s suggestion was that I produce an album for him. I thought “Oh, I can’t really handle that”. I’ve not produced an album for a long time, not since Thunderclap Newman. So I thought that it would be a better idea if we did an album together. So really, it wasn’t a great urge of mine to do an album, I don’t think in a sense that Ronnie had a great drive to do an album. It’s not an album born out of a great need. There’s no great reason we did it. We did it because we thought it was a great thing to do at the time for both of us.

Pete Townshend interview, Rough Mix bonus DVD, 2006

When he came to talk to me about doing Rough Mix together, what he asked me to do was to produce his album. He said “Will you produce an album for me?” and I said “No, I can’t do that.” He said, “But I love what you do, and I love the recordings I do at your house.” And I said, “No, I can’t do that.” And he said, “Well, will you write a bunch of songs with me?”, and I said, “No, I can’t do that either.” And he said, “Well, I’m broke!” I said, “Well, I’ll make this album with you as a performer! I’ll stand beside you and support you. But I insist that Glyn Johns produces it. I want to record with him. I would love to do an album with him away from The Who.” We had a lot of success with him, and I wanted to work at Olympic Studios as well, because it was near home. It worked out very, very well.

Pete Townshend radio interview with Jim Ladd, A Rough Mix Indeed, KMET Los Angeles, 1977

I’ve explained Ronnie’s reasons for wanting to do it. My reasons for doing the album were more… I suppose because we had a heavy year of touring with The Who in the States, and I felt a bit stultified with road consciousness, and I wanted to crack out of that. I felt a session in a studio, enjoying knocking about something without great pressure would loosen me up, and indeed it did. As the sessions were going, the old pens started and I’ve written a load of stuff since we did the album.

Pete Townshend Press Release Interview, September 1977

Thinking back, I suppose it would have been just as easy for me to have rung up Roger Daltrey and arranged to have done an album with him, or even rallied for The Who for some demos or something, but I was eager for a chance, not to do a solo album but to work in the studio with Glyn again, do something without the heavy pressure of a Who gig, and maybe meet and play with some new people. I felt sure my writing, and therefore The Who, would ultimately benefit.

Pete Townshend radio interview with Jim Ladd, A Rough Mix Indeed, KMET Los Angeles, 1977

I didn’t really make any conscious effort to avoid Who like material, definitely not. What actually happens when I write is if I write say 30 songs for a Who album, 15 of them go by the board as soon as the band get together to listen to them. There will be one that Keith will be very cold to, Keith doesn’t like for example anything that swings, in the traditional sense. He doesn’t like shuffle rhythms. So anything that’s got a shuffle rhythm… for example Rough Mix is an instrumental that’s got a shuffle, it’s got a back beat in it. Keith won’t play that. Keith is an on beat drummer. So that’s all that out the window. Roger doesn’t like anything that’s too obscure, and also doesn’t like anything that’s too bitter. One of the only ways that I could get across the bitterness that I felt at the time of the last Who album, The Who By Numbers, was by only presenting just enough songs to fill the album. If I had given too many alternatives I wouldn’t have got the stuff on. So that’s what tends to happen. Now in this case, the editing process, or the selective machinery was completely different. It’s a different person standing in a different place. From Glyn Johns (who produced the album) point of view, he wasn’t trying to produce The Who, he was trying to produce something which had no foregone conclusion, there was no preconceptions of how it was going to turn out. And Ronnie’s whole supportive thing to me, his whole desire was to get together on an album with me because he’s always liked the things that I do outside of The Who, which the general public never get to hear. And so he was triumphant when we actually started to do anything that was a little bit different.

Pete Townshend interview with Scott Muni, 1978

Rough Mix gave me confidence to do something on my own. When you know that every album that you do is going to be measured against the band that I believe is the best in the world, it makes you a bit reticent about going and doing it. I did the album with Ronnie because I wanted to get my head going again, and it really did. It wasn’t meant to be a big deal. It really got me writing. And it was good for him too, ‘cause he was just forgotten.

Pete Townshend interview, Austin Chronicle, 2007

For me, that album was a divine collaboration, a life-changing record. 1976 was a very critical and intense year for me in a whole number of different ways. I did a lot of stuff with The Who and a lot of extramural stuff too. The other thing was that the record was critically acclaimed. It made me confident that I could pursue a solo career. It may also have been the record that sowed the seed of doom for The Who. I think already by ’76, I was running out of ideas as to how to get The Who to move to the next level, if there was one.

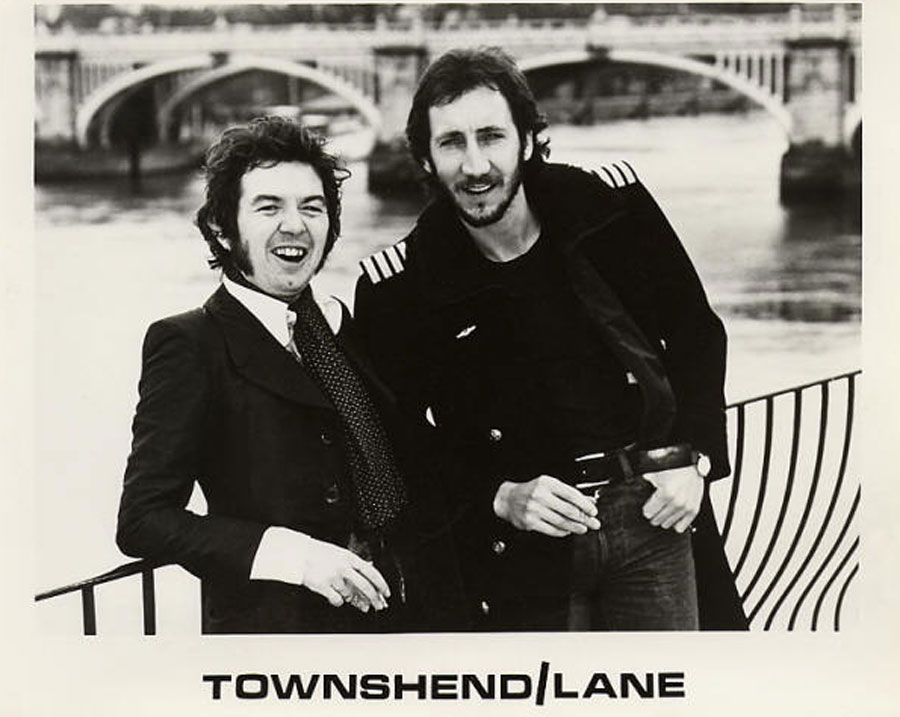

Promotional photo credit: Martin Cook

Promotional photo credit: Martin Cook

Pete Townshend radio interview with Jim Ladd, A Rough Mix Indeed, KMET Los Angeles, 1977

The album title Rough Mix is a recording connotation. In the recording business, a rough mix is a mix of the music that you recorded during the day, which you knock up to tape to take home with you to listen to over tea. It’s very sort of demeaning to Glyn Johns to call the album Rough Mix, because from his point of view he spent two weeks trying to get it right. To call it Rough Mix was a good sort of black joke for Ronnie and I to play on Glyn. Glyn liked it actually. And also, I think Ronnie and I are a very rough mix, I really do. I think we are like oil and water. One of the problems is Ronnie and me can’t play (laughs).

It was a problem for Ronnie and I to work as though we were a team. We’re not in any way similar as characters or musicians. We have the same roots. We both played in early British rock bands in the 60s. Ronnie has gone one way, and I’ve gone the other way. The Who have been lucky enough to stick together and go on to great success, and the Small Faces evolved, as probably people know by now, into the Faces, and now back into the Small Faces again. Ronnie seems to prefer riding around on a tractor than riding around in a TWA airplane and staying in Holiday Inns, I don’t know.

Pete Townshend Press Release Interview, September 1977

Ronnie’s songs are totally different to mine, and we racked our brains as to how we could bring ourselves closer musically; sing each others songs or contribute ideas for arrangements of each others songs or something. But my material is always somehow dead set in my head. It takes a hard man to change my ideas and preconceptions. I was able to gently contribute to Ronnie’s stuff, getting to play in a way I hadn’t done for years, without tension or pressure.

Ronnie’s contributions to my stuff came in a much deeper way. Not only would I not have produced the tracks I did with him on the album were it not for him, but his encouragement and enthusiasm made me try more as a musician rather than a sensationalist. When I finished a number it was Ronnie who looked proud. When I did a good vocal it was Ronnie who got the kick. It’s hard to explain, but in a word, friendship says it.

Pete Townshend interview with Chris Welch, Melody Maker, 1977

I didn’t play on Annie and Ronnie didn’t play on Street In The City, but everything else… yeah. We generally made room for each other. As far as Ronnie’s stuff was concerned I really enjoyed working on them. But Ronnie’s contribution to my stuff was much, much deeper. It’s hard to explain. For a start, I don’t think I would have done the album or the kind of material I did, if it were not for Ronnie’s encouragement. And that hasn’t just started with this album. It has been constant. Ronnie’s been one of the few people that I’ve played demos to, and he has always encouraged me to do stuff away from the mainstream of Who clichés.

Pete Townshend interview, Rough Mix bonus DVD, 2006

Ronnie had the veracity, the precision, the humour, the lightness, the colour, the sarcasm, the wit, the Englishness, but also the skill. He was a good craftsman as a songwriter. I very much respected him as a songwriter. I wouldn’t have done Rough Mix with him if I hadn’t. Sadly, I never wrote anything with him. I’ve never written anything substantial with anybody, so it’s not surprising. He could have written with me, if only I hadn’t got in the way. And he wanted to be in some sort of creative outfit with me, or with Eric, or with somebody that he genuinely loved and respected. That’s not to say that he didn’t love Kenney and Mac and Rod and the rest of them. He wanted somebody to be with him who was like he’d had in the early days of the Small Faces; a mate, a kindred spirit, but who could also up the ante. Ronnie was very ambitious.

Pete Townshend interview, Austin Chronicle, 2007

I’ve never been able to co-write comfortably. I suppose for me it’s probably about control. When I sit down with somebody else, I find it quite tricky to get past the fact that there’s a kind of creative negotiation going on, which I don’t know that I’ve got the generosity of spirit to deal with. Ronnie was extraordinary in that respect; he could work with anyone. He was so adorable but such an underestimated musician in those early days. He wasn’t a real Who fan. He wasn’t into punk rock that The Who was into. He loved coming around and listening to my demos, the little things that I did that The Who never recorded.

Pete Townshend excerpts from autobiography Who I Am, 2012

Critics seemed surprised that Ronnie Lane and I didn’t collaborate as writers. As I had never co-written a song in my entire career up to that point I thought they must be a bit dim. Ronnie never said he expected me to co-write, although later he expressed disappointment that we hadn’t even tried.

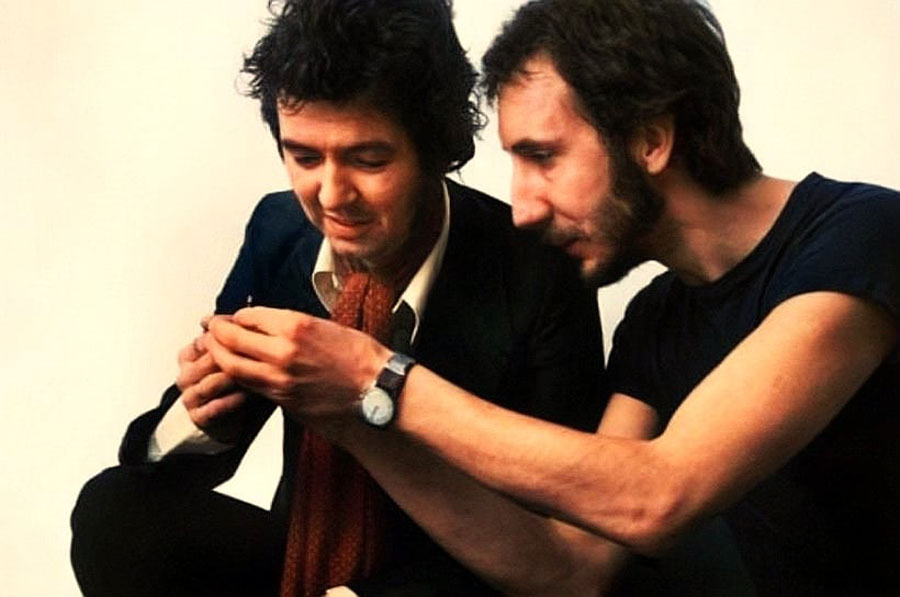

Promotional photo credit: Martin Cook

Promotional photo credit: Martin Cook

Pete Townshend Press Release Interview, September 1977

Sometimes Ronnie and I would talk about life. That would mean Ronnie insulting me and me hitting him. Sometimes Eric Clapton would come to play. That would mean Ronnie insulting him, Eric hitting him, and then falling over. Glyn and Ronnie often discussed Ronnie’s songs. That consisted of Ronnie trying to keep Glyn in the studio till three or four in the morning while he insulted him. Glyn never hits anyone, only nearly. In reality, Ronnie shone when the music was lively and the company enjoyable. He has two sides and both of them are totally terrible, I mean different. One side is quite serious and reflective, self critical and eager to fit in; the other side is tough and flippant, but also very funny. The latter emerged often and after a visit to the local brewer. Apart from coming closer to a divorce than ever before, the album was fairly uneventful. Only one broken leg, twelve hangovers, two heart attacks. No women at all. None seen whatsoever, so no problems there.

Pete Townshend interview, October 2005 (published in petetownshend.com Diaries, 2006)

Rough Mix was quite fun, though it was during this recording that I realized Ronnie Lane was suffering from some strange illness – at first I thought it was drug-related. It turned out he had MS.

Pete Townshend interview, Austin Chronicle, 2007

I can remember it was the first time when I realised that Ronnie was getting sick. We had a little argument about something; he accused me of treating my wife very badly and said something a bit indecent about me. I pushed him or punched him, and he just went flying. I thought, “Well, he’s a little guy, but God, this is a bit strange.” He really went flying. I helped him up, and I said, “What’s up?” and he said, “Oh, I just lost my balance.” And I said, “You look like you are drunk.” I went back, and somebody else in his circle said to me, “We think Ronnie might have MS.” That was the very first time I realised that was happening.

Pete Townshend excerpts from autobiography Who I Am, 2012

Ronnie and I were interviewed about the Rough Mix album on BBC TV’s The Old Grey Whistle Test. While I tried to set Ronnie up as my straight man and attempted to be funny, Ronnie wanted to be serious about the record. I appeared childish, and almost dismissive about what we’d achieved together, trying to bring up the future of The Who, even though at that time there was no future.

The time I had spent with Ronnie Lane working on Rough Mix showed me that even someone I regarded as a best friend could trigger me to fight. I fought if I was up, and I fought when I was down. When I lost my temper it was all I know to do.

Pete Townshend Press Release Interview, September 1977

When I had done the Tommy film tracks I had enjoyed working with dozens of different musicians and Glyn’s suggestion that we use musicians who suited each song appealed to me. One guy in particular I liked working with was Charlie Watts. His drumming was simple but swung like hell and added a direct spice to everything he played on. The rest of the drumming was done by Henry Spinetti. Henry had the job of trying to play like Glyn wanted him to, with breaks the way I wanted them and the speed the way Ronnie wanted it. Interesting for him! A great challenge. Luckily for the album he took no notice of any of us and contributed the major testicle.

Pete Townshend interview, October 2005 (published in petetownshend.com Diaries, 2006)

What was great was working with musicians like Eric Clapton. But the high points for me were playing live acoustic guitar with a big string orchestra on Street In the City; playing with Charlie Watts who is such a swing-driven drummer to play with; discovering John (Rabbit) Bundrick who passed through and played some Hammond.

Pete Townshend excerpts from autobiography Who I Am, 2012

The recording of Rough Mix with Ronnie is now a blur, but I remember some special moments. I played live guitar with a large string orchestra for the first time, my father-in-law Ted Astley arranging and conducting on Street in the City. I was surprised at the respect given me by the orchestral musicians. Playing with Charlie Watts on My Baby Gives It Away was also very cool, making me aware that his jazz-influenced style was essential to the Stones’ success, the hi-hat always trailing the beat a little to create that vital swing. Meeting John Bundrick (Rabbit) was also an important event in my life as a musician. He wandered into the Rough Mix studio one day looking for session work. Here was a Hammond player who had worked with Bob Marley, and could play as well as Billy Preston. Offstage he could be reckless and impulsive, drinking way too much, asking for drugs and telling crazy stories, but musicians of his calibre didn’t come around very often.

Promotional photo credit: Martin Cook

Promotional photo credit: Martin Cook

My Baby Gives It Away

Written by Pete Townshend, featuring Charlie Watts (drums).

My Baby Gives It Away (with B side April Fool) was released as a single in the US on November 18, 1977. It failed to chart.

Pete Townshend radio interview with Jim Ladd, A Rough Mix Indeed, KMET Los Angeles, 1977

My Baby Gives It Away would not be a good Who song, because it’s got a shuffle rhythm, which we would never do. The Who do on beat, like the kind of rhythms that you hear coming from today’s British punk groups.

Pete Townshend interview, Trouser Press, May 1978

My Baby Gives It Away is actually a song about my old lady, and she didn’t think it was sexist; she was the first person I played it to. I suppose it was a song about me. About my realizing what idiots men really are for chasing after what they have in their own backyard; chasing after trouble; chasing after wounding relationships; hurting people. Of course, women are half to blame for that as well. I think maybe you don’t realize until you’re getting to the point where you begin to think you might be past it. You start to think about what is wound up in a casual affair, a quick one-night job with some bird in some hotel room. What is it? What does it mean? The spiritual ramifications are one thing, your own moral values are another. It’s a declaration of mistrust but most of all, most important, is that for the sake of a physical thing you’re going into another human being, becoming enmeshed with them and then tearing yourself away. It’s just the craziest thing to go around doing – crashing into things, literally. It doesn’t detract from the beauty of the experience or from the joy of sex as God bloody handed it down. It’s just that – well, teenage promiscuity is one thing – experimentation – but when you get to be 22, 23, 24, by that time if you haven’t got your shit together, forget it. My Baby Gives It Away is really about that. I suppose it is openly sexist, but it’s not a self-conscious statement. It’s sexist in that it says “I am a married man and my old lady loves me enough to let me have it when I want it” – which is a bloody lie.

Nowhere To Run

Written by Ronnie Lane, featuring Rabbit (organ), Henry Spinetti (drums), Peter Hope Evans (harmonica).

Pete Townshend interview with Chris Welch, Melody Maker, 1977

I did a hell of a lot on Nowhere To Run. I felt I had achieved something as an arranger on that one.

Rough Mix

Written by Pete Townshend and Ronnie Lane, featuring Eric Clapton (lead guitar), Rabbit (organ), Henry Spinetti (drums).

Annie

Written by Ronnie Lane, Kate Lambert, Eric Clapton, featuring Eric Clapton (6 string acoustic guitar), Graham Lyle (12 string acoustic guitar), Benny Gallagher (accordion), Charlie Hart (violin), David Marquee (string bass).

Pete Townshend Press Release Interview, September 1977

Ronnie stayed home to finish Annie a song about a beautiful lady who looked after his kids and home while he and his wife spewed up in a local boozer back near their farm in Wales.

Keep Me Turning

Written by Pete Townshend, featuring Rabbit (organ and piano), Henry Spinetti (drums).

Keep Me Turning (with B side Nowhere To Run) was released as a single in the US on March 18, 1978. It failed to chart.

Pete Townshend, In The Attic webcast, 2006

It’s like a country song really. There’s a bit in there about Jack the grocer. A guy called Keith West, who was in a really great band called Tomorrow, a psychedelic band from that period in the late 60’s. Steve Howe, who went on to play in Yes, was their guitar player. They were really great. We used to play with them up in Tottenham. Keith West was the singer, and he did this thing called an Excerpt From a Teenage Opera (1967), it had a children’s chorus in it. It was a hit single that went straight to number one. It had a really great bit in it that went (sings) “Grocer Jack, grocer Jack, duh duh duh your coming back.” So in my song it’s got “Grocer Jack are you ever coming back. Will your operatic soul turn black.” It’s all about Keith West’s opera. There’s also this bit about the messiah, which is “Here comes the messiah, oh god, I guess I missed it again.” Because when I found out about Meher Baba, the rumours were that this was the second coming of the Messiah, whether you believe it or not. Before I got to see him in India, he died. So the feeling was that I kind of missed that contact with this master. And the bit, things must go to 110, this is the number of times I missed the opportunity – just out of the air because it rhymes – the number of times it’s possible to miss your spiritual moment, as you watch it go by.

Catmelody

Written by Ronnie Lane and Kate Lambert, featuring Charlie Watts (drums), Mel Collins (saxophone), Ian Stewart (piano).

Misunderstood

Written by Pete Townshend, featuring Peter Hope Evans (harmonica), Julian Diggle (percussion), Bijou Drains (gulp).

Pete Townshend radio interview with Jim Ladd, A Rough Mix Indeed, KMET Los Angeles, 1977

Well I wrote Misunderstood with a bit of a tongue in cheek attitude, obviously. It means a lot of things. I can’t really explain what it means. I suppose I wrote it as a bit of a gag. I was thinking about Fonzi at the time when I wrote it. I met that geezer, whoever he is, what’s his name, Henry Winkler. His real name’s better than Fonzi I think. I met him, I was in a record store in LA, and I saw him. When you are in LA, you get used to seeing stars about, you really do. And half the time you have to be very careful not to open your mouth and say anything or draw anybody into conversation, because they could just be an extra that you saw in Planet of the Apes or something, and you think you know them or you think they are famous, but really they’re not. Anyway, I sort of nodded, and he started following me around the record store. He had this girl with him, so obviously there were no homosexual overtures or anything. But he was following me like you know, like fans rarely do! If you see a Who fan in the street, they don’t follow you around. They normally are very discursive, and they sort of say “Hello Townshend!” and that’s it. Anyway, Winkler was following me around and finally he comes up to me and said “I just want to tell you how deeply you have effected my work.” And that was it! I mean I really like the whole sort of Fonzi thing, but for a start it’s fantastically sexist isn’t it. And I suppose that’s one of the things that’s sexist like the Stranglers are sexist, I mean sexist like the fifties were. I thought that’s weird the difference that exists between, although there are a lot of similarities apparently, between the old fifties James Dean type of kid and today’s punk kids. And yet there’s this common denominator, which is this desire to be misunderstood.

Pete Townshend liner notes, The Best of Pete Townshend, 1996

Misunderstood was a song which I expect was flown past The Who at some point, and probably Roger said something like, “Well, it’s great, Pete, but it’s obviously yours, isn’t it? I don’t know that I can sing that.” It’s not actually a song about how I felt particularly. I was just writing a song about the kind of James Dean syndrome – you know, I would much prefer to be confused and gorgeous than as I really am (laughs), which is, as I think I say in the song, fairly easy to penetrate, but that’s another kind of sub-teenage angst all of it’s own.

April Fool

Written by Ronnie Lane, featuring Eric Clapton (Dobro & foot), David Marquee (double basses).

Pete Townshend radio interview with Jim Ladd, A Rough Mix Indeed, KMET Los Angeles, 1977

From my point of view, the most successful of Ronnie’s tracks on the album is April Fool. I think it pleases me greatly because it’s really a typical… I don’t know if it’s a typical Ronnie song, it just really sums him up for me. It’s just a perfect expression. Musically it’s very gentle. Beneath Ronnie’s sometimes tough exterior I think does lurk a very gentle person. And it’s typically self-effacing. If Ronnie ever wants to make anybody laugh, it’s usually by running himself down in some way, like appearing at the session too drunk to stand up, a little like Keith Moon’s self destructive thing, but coming from a slightly different tack. April Fool is about him. I also really like on April Fool, the thing that really brought it out was the Dobro by Eric Clapton. He did it in one go, he just sat down, tapped his foot and played this thing the first time. It was very weird, because Eric jumped up at the end of it sitting there quietly playing this gentle Dobro thing, jumped up and sort of applauded himself, like he had just done a wild raving Ted Nugent guitar solo. He was really knocked out with it, as were we.

Street In The City

Written by Pete Townshend, featuring Edwin Astley (orchestral score), Tony Gilbert (orchestra leader), Charles Vorsanger (2nd violin), Steve Shingles (viola), Chris Green (cello), Chris Laurence (bass).

Street In The City (with B side Annie) was released as a single in the UK on October 28, 1977. It failed to chart.

Pete Townshend Press Release Interview, September 1977

One interesting song to do was Street In The City. I wrote the words in Fleet Street while waiting for a shop to open. There was this character up on a high ledge. A little group of people started to gather. A few out of work journalists staggered out of the Wig and Pen thinking that God might have arranged a scoop for them. A policeman hurried across the street as the man up on the ledge started to inch his way across the broad expanse of glass, his back against it. Someone ran to a phone and the policeman started to stop the traffic. A couple of blokes got out of their cars and looked up. I lent against the wall and looked at the people looking. Suddenly, the bloke on the ledge pulled a leather out of his pocket and started cleaning the bloody windows! Everyone pretended they knew all along that he was a window cleaner rather than a potential suicide and carried on. But you should have seen their faces, they looked positively cheated.

Glyn suggested I do the song live with a double string orchestra and we looked around for an arranger. It struck me as we ran through names that my father-in-law Ted Astley might be willing to have a go. Ted had written lots of film music, but had a little time on his hands while he watched the fifty ninth re-run of The Saint for which he wrote the theme and incidental stuff. The score turned out great, and it was a real kick for me to sit and play guitar with a lot of violins and things. Ronnie didn’t come!

Pete Townshend radio interview with Jim Ladd, A Rough Mix Indeed, KMET Los Angeles, 1977

I often paint pictures. 5:15 was a picture painting exercise, 5:15 from Quadrophenia. In fact I wrote 5:15 in Carnaby Street watching the world go by, and I wrote Street In the City in another London street, Fleet Street where all the press world is based, waiting for somebody in the street. And I just tell about a little incident that happened where a guy was up on a ledge and a lot of people thought he was going to jump off, and then at a key moment he suddenly produces a washing leather and started to clean the windows. I got out my pencil and started to write about it. Let’s face it, it’s guitar and voice essentially, and on top of it is superimposed an orchestral arrangement. The consection of the orchestral arrangement is particularly interesting because it is definitely not a kind of thing which I would ever come up with say, if I did something on the synthesizer. And that is because I haven’t got the skill of the man who did the arrangement, who is actually, coincidentally, my father-in-law! We are a family butcher you know (laughs). I asked my father-in-law to do it, Ted Astley, who’s been an orchestral arranger and film music writer of great success in this country for many years. He put this arrangement together ever so quickly, and it’s a double string orchestra thing with a large string orchestra and six big basses. I actually sat down with the orchestra and played to them on the guitar, which was a really good experience. I haven’t played with an orchestra since Lou Reisner’s Tommy. But it’s not really that unique. Whenever you write a song you tend to go through it in your head in a various number of ways, and one of those ways might be thinking about how it would sound with a bloody great orchestra. I think it stands out because it’s more of a cooperative effort musically than anything I’ve ever done. I’ve contributed the music and the song, and Ted Astley has really contributed a very sort of innovative arrangement around it, an impressionist piece. I paint pictures with using the words, but Ted paints more vivid pictures with using the orchestra. I’ve actually thought about doing a complete album of stuff like this with Ted, because Street In The City has attracted so much attention. This is the track that everybody seems to be drawn to, sometimes because they are confused by it, and sometimes because it fits their idea of where music should be going. A lot of people who don’t like it the first time grow to like it. I think it could be a pointer to the kind of things I might enjoy to go on and do.

Pete Townshend liner notes, The Best of Pete Townshend, 1996

Street In The City is a song about walking through a city and picking up paranoia everywhere, which I’d written about before, for example, with Who Are You, and I’d done it with 5:15 on Quadrophenia. I’d written them by deliberately going to somewhere like Oxford Street and picking up feelings from people and writing them down quickly. And I did that with Street In the City, only this was a more distant view, it was looking at people in office blocks, and trying to get a sense of, you know, “That man over there painting that wall – I wonder what he’s like in bed with his wife,” and, “That priest – I wonder what his childhood was like,” trying to project and create characters.

At the time, Kit Lambert and I were talking about doing a project which would eventually embrace his father Constant Lambert’s unrecorded catalogue of compositions, and we wanted an orchestral collaborator for that, and the way that we thought we would start was with a series of experiments orchestrating compositions of mine, and I suggested my father-in-law Ted Astley, who had done film music, and this was the first thing that we tried. The whole thing was an experiment to see if you could make an argument that there was a form of songwriting where the orchestra was absolutely necessary. And what we, of course, proved was that it wasn’t – that it was fascinating and wonderful and interesting, but it wasn’t essential, that used to support the human voice, the string orchestra becomes decorative.

Heart To Hang Onto

Written by Pete Townshend, featuring Boz Burrell (bass), Rabbit (Fender Rhodes), Henry Spinetti (drums), John Entwistle (brass).

Pete Townshend stage banter, Ronnie Lane Memorial Concert, 2004

This song is really about Ronnie, and I didn’t tell him it was about him when we recorded it, but he sang on it, and it’s called Heart To Hang Onto.

Pete Townshend interview, October 2005 (published in petetownshend.com Diaries, 2006)

Heart To Hang On To has become one of the most special songs in my solo repertoire, I’m stunned we rejected it as Who song, but we did.

Till The Rivers All Run Dry

Written by Don Williams and Wayland Holyfield, featuring Henry Spinetti (drums), Boz Burrell (bass), Eric Clapton (Dobro), John Entwistle and Billy Nicholls (vocal help).

Pete Townshend radio interview with Jim Ladd, A Rough Mix Indeed, KMET Los Angeles, 1977

Till The Rivers All Run Dry is there because of a mutual fascination that Ronnie and I have got for Don Williams. He’s an amazing bloke and an amazing musician. Eric Clapton met him. Eric and Ronnie are good mates and were spending a lot of time together, and they invited us to the Hammersmith Odeon to see Don Williams. We didn’t really know what to expect, we knew he was a country artist, but I didn’t really realize quite how unique he was. We sat down and we listened, and Don started to play, and this really sort of spiritual piece descended on the Hammersmith Odeon. When he sang Till The Rivers All Run Dry, Ronnie and I just looked at one another and realized that this song was a bit like a hymn, like an expression of some sort of spiritual longing. The words go “Till the rivers all run dry, till the sun falls from the sky, till something something I’ll still be needing you”. I suppose it could be a song about a man always needing a woman he’s in love with, but Ronnie and I saw it as people always living and requiring that need for something. Each of us identifies it in a different way. If you don’t need anything, then you are sort of emulsifying. You got to need something. For Ronnie and I it was very special because after the first few bars of the chorus we both looked at one another and said, this is a real Meher Baba song. The kind of song which Meher Baba, who is this Indian spiritual master that we both have followed now since ’66, would have loved. And the kind of song which his disciples would love to listen to.

Researched, written and produced by Carrie Pratt