Pete Townshend’s conceptual solo album and film White City was released 35 years ago this month!

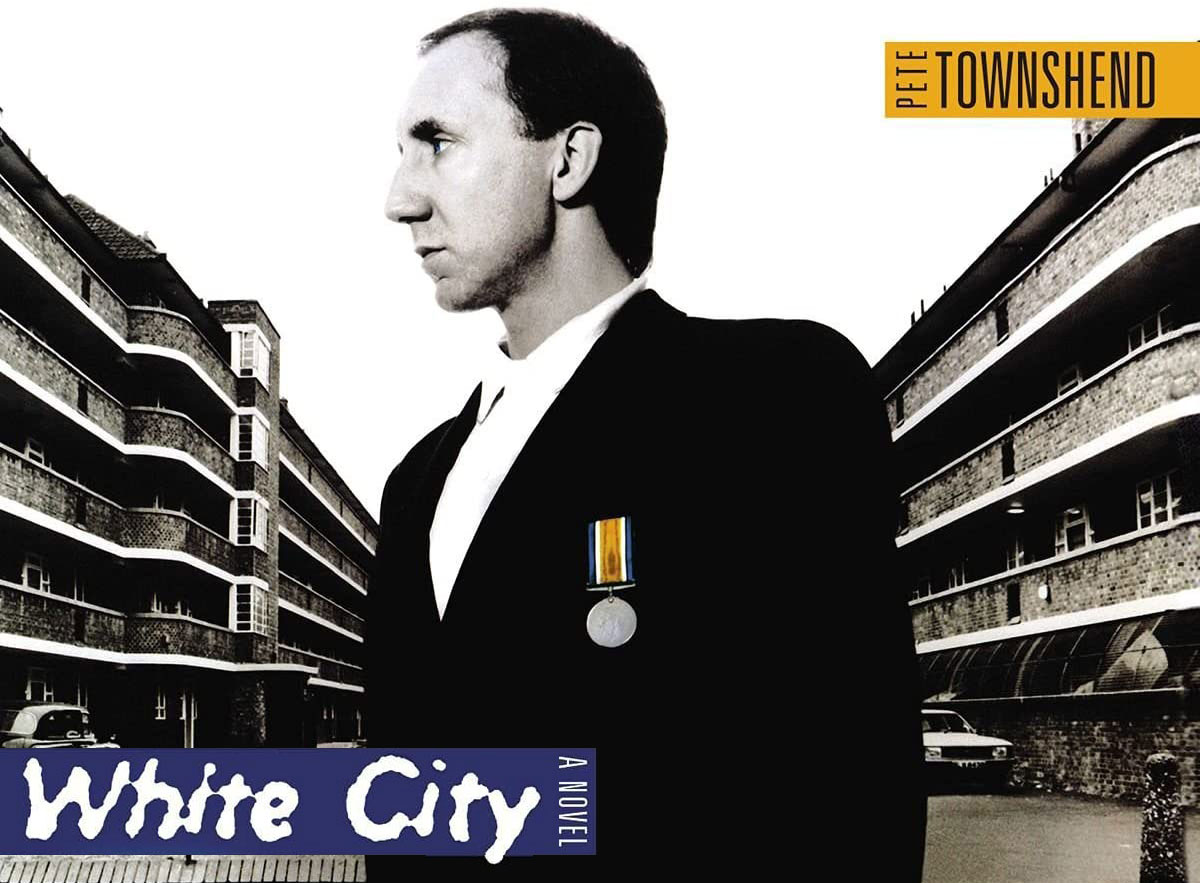

The album, entitled White City: A Novel, was released on November 11, 1985 by Atco Records. Recording began in late 1984, and took place at Pete’s Eel Pie Studios in Twickenham and Soho, with additional work done at George Martin’s AIR Studios in London. It was produced by Chris Thomas and engineered by Bill Price, the same team that worked on Pete’s previous solo albums, Empty Glass and All the Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes.

Pete recruited a number of top flight musicians to record on the tracks, including John "Rabbit" Bundrick, Steve Barnacle, Tony Butler, Chucho Merchan, Pino Palladino, Phil Chen, Simon Phillips, Mark Brzezicki, Clem Burke, Peter Hope-Evans, Kick Horns, and various singers on backing vocals. Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour played guitar on Give Blood and White City Fighting, and also wrote the music for White City Fighting, which was included in a batch of song lyrics that Pete had written for Gilmour's 1984 solo album About Face. David Gilmour ultimately gave the song back for Pete to use on his own solo project, and White City Fighting became the central concept for Pete’s album.

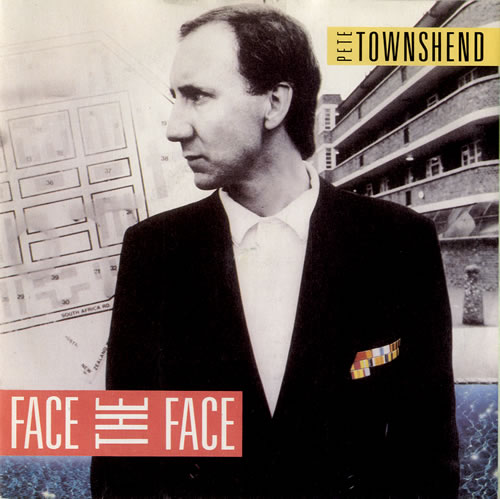

The album had moderate chart success, peaking at #26 in the US and #70 in the UK. The singles that were released were Face the Face (B-side Hiding Out), Give Blood (B-side Magic Bus cut from Deep End live), and Secondhand Love (B-side White City Fighting).

The songs on the album were inspired by the White City Estate, a housing project located in the White City district of West London near Shepherd's Bush, the neighborhood where The Who got their start in the early 60's. Pete used to drive through the area as a short cut on his way to work at his publishing job at Faber and Faber in the 80’s. He was interested in how the streets were named after areas in the British Empire, which tied into his idea of writing about his roots in post war England and the decline of the British Empire. Pete wrote a teleplay that incorporated his songs, which was adapted and made into a short film by Australian director Richard Lowenstein.

The White City film features actors Andrew Wilde and Francis Barber, who play Jim and Alice, a couple living on the estate who are having marital problems. Jim is loosely based on the Jimmy character in Quadrophenia, who is now middle aged and struggling with personal problems. Alice is an instructor who teaches synchronized swimming at the White City pool. Pete Townshend appears as a version of himself, a rock star who has returned to his old neighborhood to play a charity concert at the pool. Interspersed throughout the film are black and white scenes with a young boy portraying Jim’s traumatic childhood memories. Pete was going through therapy at the time, and had just published his book of introspective poems, Horses Neck. The film explores autobiographical elements of Pete’s own life, similar to his other works.

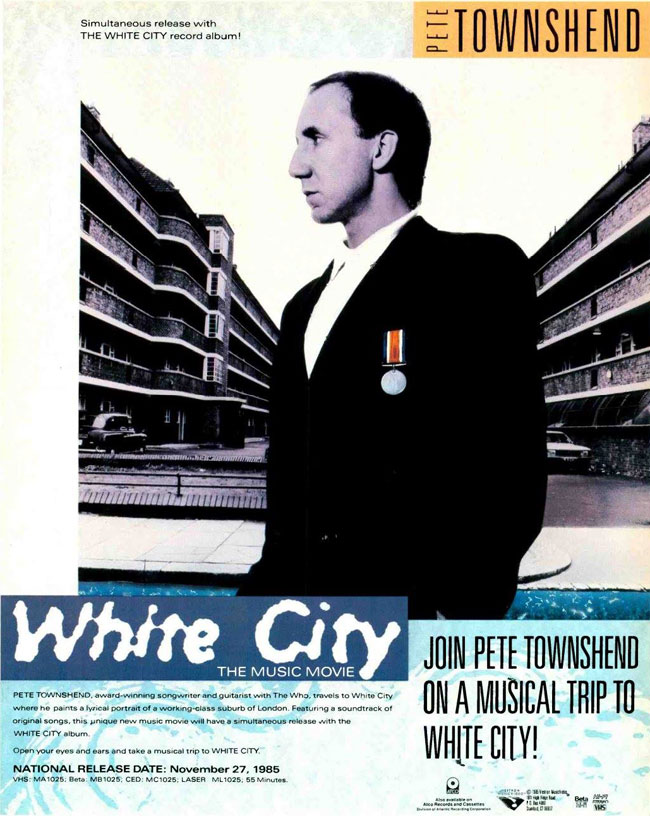

White City: The Music Movie was released on November 27, 1985 by Vestron Music Video. In addition to the 45 minute film, the videotape also featured an interview with Pete on location in White City, and a recording session at Eel Pie Studio for the song Night School, which was not included on the album until it appeared as a bonus track on the 2006 CD reissue. White City was later made available on LaserDisc, but was never released on DVD or Blu-ray formats.

The songs featured in the movie were Give Blood, Secondhand Love, White City Fighting, Hiding Out, Face the Face (with Emma Townshend), Come to Mama, and Crashing by Design. The film opens with an extended remixed version of Give Blood, showing Pete in the recording studio jamming on his Gretsch 6120 guitar. Snippets of songs on the album served as background music throughout the film. Edited footage of some of the songs in the film were also used as promotional rock videos on MTV and other music programs.

To promote White City, Pete formed a band called Deep End, referring to the deep end of the swimming pool where they held their concert in the film. Pete debuted the Deep End on Jools Holland’s show The Tube on October 11, 1985. They also performed at two concerts for Pete’s Double O charity at London’s Brixton Academy on November 1 & 2, 1985, the Snow Ball Revue charity show for Chiswick Family Rescue Centre on December 22, 1985, and the Rockpalast German TV show in Midem, Cannes on January 9, 1986. Selections from the Brixton shows were released on Pete Townshend’s Deep End Live album and video in 1986.

The Deep End included the following members: Pete Townshend (vocals, guitar), David Gilmour (guitar), John "Rabbit" Bundrick (keyboards), Chucho Merchan (bass), Simon Phillips (drums), Jody Linscott (percussion), Peter Hope-Evans (harmonica), Billy Nicholls, Cleveland Watkiss, Chyna (backing vocals), and Kick Horns. Most of the musicians (excluding David Gilmour) formed the basis of the big backing band for The Who’s 25th anniversary tour in 1989.

To celebrate the anniversary of White City, here is the history told in Pete Townshend’s own words, sourced from various interviews and writings.

The White City Estate

Pete Townshend, documentary for White City, The Music Movie, 1985

White City is an estate built before the last war. I think its intention was to create a sort of small garden city, as we call them in Britain. I was driving through the area quite a lot. I found a short way home, and at first I was struck by the fact that all the street names were connected with the British Empire. I had been working on an idea which was based on my roots as a post war child, and the way it relates to the decline of the British Empire. I suppose it was one of the first big council estates built in the UK, and it’s gone through various periods of decline really. It’s gone downwards. But it’s a very electric and alive place. It’s got a big immigrant community, a lot of Irish, a lot of Caribbeans, mixed in with the obviously indigenous community. And right now there’s a big influx of gypsies and travelers. It’s bordered on one side by what used to be the White City Stadium, and the other side by a great big highway. It’s defined by four walls, it’s very much like a fortress.

Pete Townshend interview, South Bank show, November 1985

I was brought up very near there. White City was a kind of legendary place for me. The first time I arrived on the estate, the first thing that struck me was that it was a symbol really, of post war Britain. It obviously had been established just prior to the war to accommodate the incredible wide variety of new British, Irish immigrants, Caribbean immigrants, and the indigenous population. In a way I was searching for some kind of feeling of roots I suppose. I was writing a story called White City, which was about how England has changed since the war. And how I saw my childhood as being different from the childhood of contemporaries of mine that were perhaps 10 or 15 years younger. And then I suddenly discovered that despite that fact that it was meant to be a symbol of new Britain, if you like, it still had the taint of the old empire. All the streets were named after places connected with the empire, like Bloemfontein Road, South Africa Road, Canada Way, Australia Road. The word apartheid came into my mind, and I decided to use that word as a way of describing the estrangement of the two main characters in the story. They were being forced apart by rules and regulations that are sort of endemic to the way they were expected to live in a place like this. A lot of single parent families live on this estate. The important point is that wherever I was brought up, whatever happened to me, however I grew, I feel that that estate is closer to my idea of home than anywhere on earth. And I think that’s quite strange. And it’s not something I’m inventing, I’m actually responding to a solid feeling. What I’m trying to reinvent, if you like, is the line back. Why am I where I am today, and how has it happened, and why is it that I’m so deeply rooted in that kind of British microcosm? Why don’t I feel like a musicians son, which is what I am. Why don’t I feel like an upper middle class kid, which is what I am. Why do I feel so rooted in that particular cosmopolitan mixture of immigrants and of travelers? It’s strange. I think partly, I became a traveler, I became an immigrant, I became a transient, an itinerant, an outsider, through my work.

Pete Townshend interview, NBC Entertainment, White City album party, 1985

I used to drive home back through a familiar territory, the White City Estate, which lies just next to Shepherds Bush, which is where The Who’s career really began. The first show that I really played with Roger’s group was in a small club in Shepherds Bush, and later on we kind of consolidated our career at a club called the Goldhawk Club in Shepherds Bush. The White City Estate is just on the outside of that between Shepherds Bush itself and a motorway. And I used to cut back through it. I was looking for some place that would act as a symbol setting for a story which I had in mind about life in post war Britain. I suddenly realized this place contained all these street names that were connected to the British Empire, Australia Road, Canada Way, New Zealand Road, South Africa Road. And then I thought, White City, it’s such a wonderful name, this promise of a vision. Then I looked at the history of it, and it was actually built as an estate. Part of the original blurb was “a small city which would contain the new British of a new Britain.” So, as a result of a short cut I compounded the whole notion.

Pete Townshend interview with Robin Denselow, Guardian, November 1985

The idea for the White City film came from my nostalgia for that particular place. I used to go to the dog-track with my father. The White City Estate is a model fortress, with everything that’s currently wrong with Britain, but at the same time an illustration of the potential, ambitions and aspirations which ordinary people have.

Pete Townshend interview, In the Studio radio, 1985

It’s really about empire, about nationality, about neighborhood, about community, ghettoisation. All those things. The neighborhood I grew up in was really rather strange, and the White City was really at the center of a bunch of neighborhoods. I suppose it was one of the first attempts to gather together all the different individuals who were looking for a sense of belonging. This is in London of course. Caribbean’s that were new to the country. The Irish community that gathered around the area in Hammersmith. The Anglo-Saxon protestant bunch that had fought in a couple of wars, and wanted to get back to work and have a quiet life. The gypsy community who were being urged to move out of their caravans and live normal lives. And of course the Asian community who were starting to come to the UK. This was in 20’s and 30’s, at the turn of the century. And the White City was one of the first big experiments to bring all those people together. So when we hit the 60’s, particularly the very early 60’s, it was interesting to me as a kid, I remember being in this mod group called the High Numbers, which later became The Who, with a bunch of mod fans. And those groups of fans would be quite an ethnic mix.

Pete Townshend interview, Rockline radio, 1985

I drove right through White City on the way to the station we are sitting in right now. It’s an estate, what you call over there a housing project. It really does exist. It’s a place that’s been around since the 30’s. And when we played in Shepherds Bush when The Who first started, a lot of our fans came from that place, so it’s always had special importance to me.

The story of White City

Pete Townshend interview, Off The Record, 1985

The story is very simple. I started to drive through the estate on the way back from London. One day I noticed that all the streets were named after places in the British Empire. Then I saw it was a rather sinister implication that quite a few of the names were connected to South Africa, Durban House, Bloemfontein Road. Then I thought, “ah, this is interesting,” because I was very concerned at the time reading a lot about South Africa and apartheid. I’m not one of those lefty individuals who just criticizes South Africa out of hand. My reason, my passion for the problem in South Africa is because it’s so close to ours, as events recently have shown. Seems to me like a love story gone wrong. Like a country with so much potential with it’s brilliant white community who are capable of earning millions, I know it’s got a lot to do with gold but it also happens that the South African money people, the financiers, are brilliant people. They are equally as good as the ones on Wall Street, and the ones in our city. It’s another Hong Kong in a way. And this fantastic rich indigenous African population are separated! They’re not even allowed to make love. It just seemed to me like a potential love story going wrong. I thought I would try a metaphor, a very simple metaphor. A couple who live on the White City Estate, who are estranged. They are prevented by some external circumstances from properly meshing together. And the story grew from there. It’s very simple, but it works I think.

Pete Townshend interview with Kristine McKenna, Spin, 1986

The idea of White City all springs from a situation that exists in Britain right now. The central point I’m attempting to make is that men have somehow been brainwashed into sacrificing themselves for causes which are said to be greater than themselves and which they don’t understand. We as a society have all been complicit in encouraging them to sacrifice themselves. Now that the idea of great patriotic causes has been tarnished, we see a tragedy unfolding: the tragedy of young men in the past who willingly threw themselves into futile bloodbaths to amuse chessboard generals and the tragedy of emasculation in the present due to the fact that it’s very difficult for Englishmen to find work. The intent with White City was to suggest that it doesn’t have to be this way. Originally I was going to call it The Tragedy of the Boy. With the advance of feminism in western society and with women’s capacity to have children and bring them up, women can shape the future. I don’t object to feminism, but I think men should have a version of it for themselves.

Pete Townshend interview with Tony Fletcher, Jamming, May 1985

It’s actually a continuation, it’s looking at the hero of Quadrophenia as a 25-26 year old, living in that area now, and what’s happened to him. What I really liked about Quadrophenia was it was a the first time I ever sat down and wrote songs about someone else. What I think has been great about the last couple of years is that I’ve risen above a lot of the personal problems that I’ve carried along for the last twenty years like a great big blubbering adolescent.

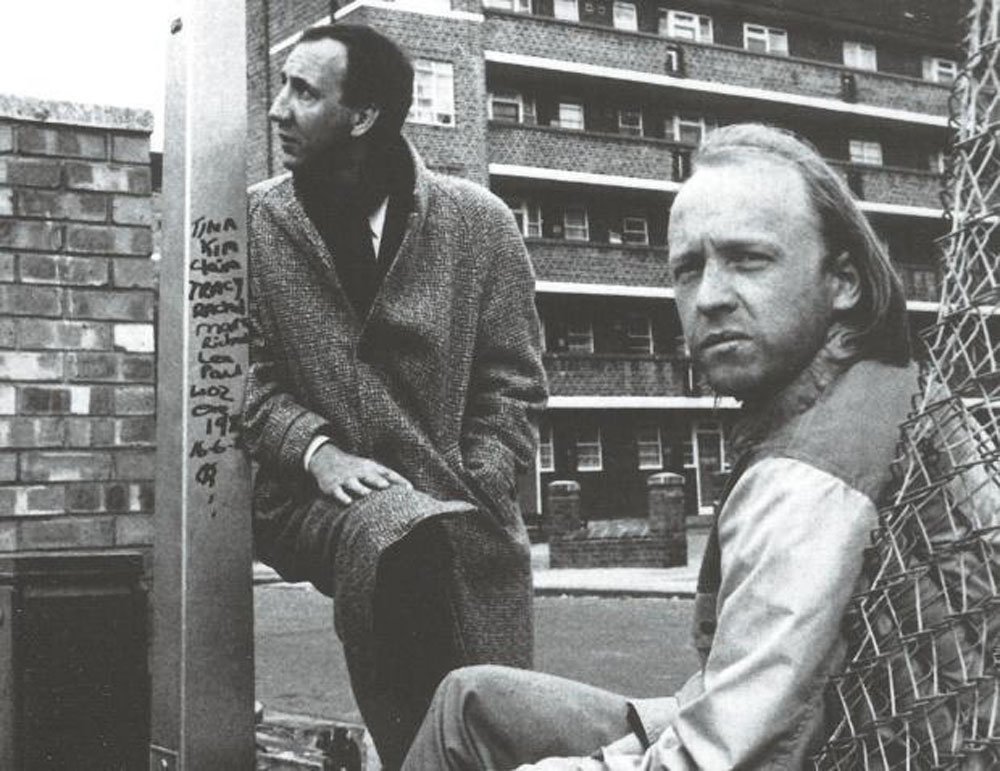

Pete Townshend and Andrew Wilde on location for the White City film. Photo credit: Malcolm Heywood

Pete Townshend and Andrew Wilde on location for the White City film. Photo credit: Malcolm Heywood

Pete Townshend, documentary for White City, The Music Movie, 1985

White City is an extension of everything that I’ve done before. It follows on the story of Quadrophenia in some way. Jimmy might be Jimmy from Quadrophenia twenty years on. It’s set in the present day with flashbacks to about 10 or 15 years ago. The film is not meant to be a period piece in any sense. The story is what’s important. The story of the relationships, and the way in which these two people work out their relationship.

The two main characters, Jim and Alice, are younger than me a little bit. My generation, I was born practically when the war ended. I think I was brainwashed like so many people into believing that success was tied up with the pursuit of heroism. That seems to be very much what the first wave of 60’s rock and roll musicians perpetuated. When I looked at the kind of story that I wanted to tell, I wanted to talk about people that were breaking those traditions. People who hadn’t suffered from the same type of mores that I had. Jim for example hasn’t done what I’ve done. He hasn’t felt the need to escape, he hasn’t felt the need to run off and travel the world. He hasn’t felt the need to make lots of money. He’s not been driven in that same way. He’s quite happy to live on the estate and his life is completely established in the microcosm that it represents. Alice is one of the new breed of women. She thinks for herself, she acts for herself, she doesn’t accept the old role. She’s a feminist, she’s active in the community on her own terms.

In the film I play very much myself really. Someone based on somebody my age, with my accomplishments. Somebody who has travelled around and come back to try and find some roots. And he’s surprised, I think, as I was surprised when I did go back and did my recceing around to talk to people, to find that there’s a remarkable degree of optimism, particularly among the very young. I feel that when I look at people maybe 5 or 10 years younger than me, I wouldn’t say I’m jealous of them, but I do admire the way they’ve started to break with the old traditions, which I do feel very embedded in me. I still feel the best thing that could have happened to me was that I’d have been called up, put in the army, and sent out to some battle field. People might think that’s sick, but I think that I was brought up to do that, trained to do that, and I respected people who did that. My father did it, my grandfather did it, and I had to do it in rock and roll.

Pete Townshend interview, NBC Entertainment, White City album party, 1985

The drift of the whole story really, is that what I found when I went back, and what I admired about the people was that they were finding a new way to deal with their problems on a day to day basis. They weren’t running away or seeking ways to become heroes, and get medals. I suddenly realized I had done a hell of a lot of chasing after heroism and nobody had given me a medal. That’s why I gave myself one on the record cover. I thought, “I’ll give myself a medal.”

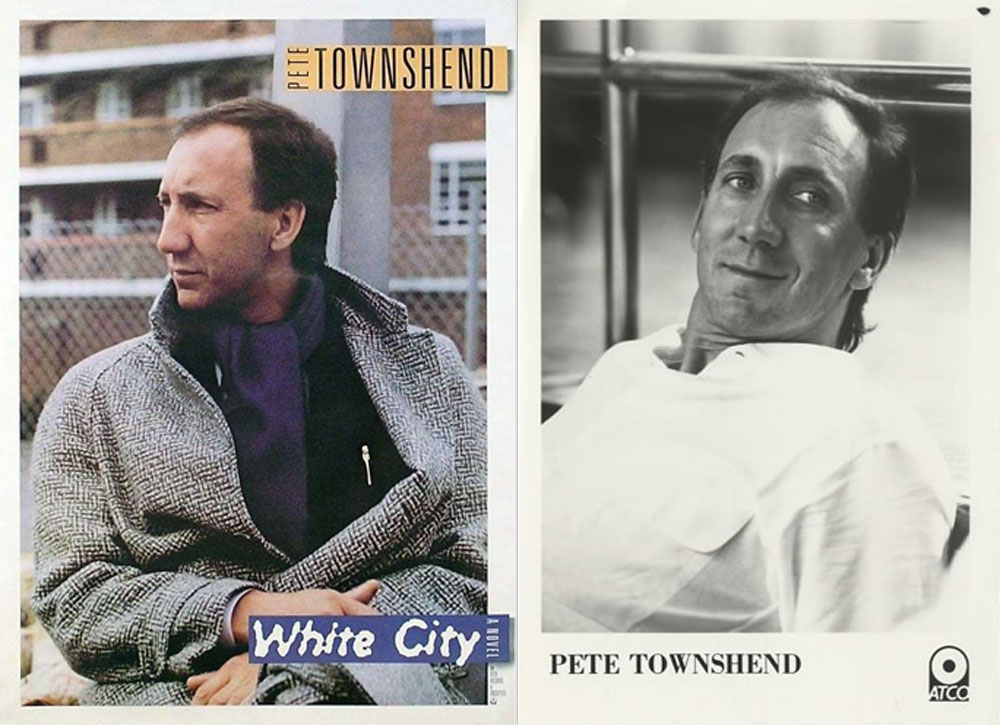

Promotional poster and press release photo.

Promotional poster and press release photo.

Pete Townshend interview, French TV, 1985

In the film I play someone who has fallen for the old con trick. I have gone away to other countries, and raped and pillaged, and smashed up hotel rooms, and got my money, and come home. Almost like somebody who was in an army or commando troupe. And then being treated like some kind of second class individual. And actually for a long time as a teenager, I was feeling confused. And I remember saying to somebody once, with all this work, and we pay all these taxes, but nobody ever gives us a medal. So on this album, I finally give myself my first and last medal. And it’s really a medal as empty in value as any of the medals which people in the last war carry around with them on Remembrance Day. It’s a sad image, the medal. It’s a symbol of tragedy and futility. I think for men who have died, a medal means something. But for men who survived, a medal means the memory of friends who are lost. The memory of blood that was shed, which apparently doesn’t have any meaning. A medal means guilt that somebody feels because they survived and their friends haven’t. I feel that guilt. I feel the guilt that I have survived, and Keith Moon didn’t survive, or that Brian Jones didn’t survive. And the medal, in a sense, is the same kind of symbol.

In this particular piece, I wanted something that told a story about people who had grown up, as I did, but who had not run away, as I did, to seek their fortune and other ways. I went off to be with a rock and roll band, went to America, went to Europe to travel the world. And I wanted to go back and take a look at people who stayed at home and see how they dealt with their problems, and how they had grown and evolved, and how they were seeing life. I didn’t particularly talk to young people in the White City, I spoke to people who were between 25 and 35 years old. And then I spoke to a lot of school kids, very young children. I spent two weeks there talking to people. I think the main thing was that the people on this particular estate, which is quite a tough place to live with a wide variety of ethnic groups, Caribbean, Irish people, there were a lot of gypsies when I was there. They weren’t bound to run away. They weren’t going to be driven to run away from problems that society has presented, which is the old British way of doing things. You know, running away to sea, running away to war, or running away to battles, or whatever. They weren’t going to allow themselves to be driven out.

In White City, there are pools, playgrounds, pubs, medical places. But there is also this great big swimming pool, which for most people is like the church. I always felt that the rock stadium is like a church. I very much wanted to use this symbol, that we have a concert of some sort in the swimming pool on the White City Estate. When I was young, I used to swim all the time, and it was one of my main ways of enjoying myself. And I wanted to bring a few things together, so in the film I play a concert, which was essentially for charity, in the swimming pool. Another thing I did was use synchronized swimming, because in the Olympics they had those synchronized groups for the first time, and I thought it was wonderful.

Pete Townshend interview, South Bank show, November 1985

In the end I chose a very simple story about two estranged lovers living on the White City Estate. Which for a variety of reasons seemed to be the perfect setting for all of the feelings that I had. I just felt that a child brought up in a pub would have had certain experiences which did relate to mine. In other words, a mother and father running a pub with a young kid would spend a hell of a lot of time fussing about with their customers, and perhaps not enough time fussing about with their children. I definitely felt this in my early childhood about my parents. My father was always away on the road entertaining people, which I was very proud of and felt very involved, but at the same time I sometimes wondered what was so important about them. So in that respect Jimmy is similar. I admire him in one way, because he hasn’t left. He hasn’t given up the ghost. I did. I gave up the ghost very early. Emotionally I think I gave up the ghost when I was about 14, I thought, “Screw all this, I got to get out.” So Jim is dissimilar in that he stays. My experience is pretty limited. I’ve done a lot of the same thing. So when I come to get to grips with a story and make it fruity enough and real enough to speak truthfully and loudly, I have to stick to what I’ve actually experienced. And I did experience estrangement and reconciliations.

The White City film

Written by Pete Townshend

Adapted and directed by Richard Lowenstein

Produced by Michael Hamlyn and Walter Donohue

Starring Andrew Wilde as Jim, Francis Barber as Alice, Pete Townshend as himself

Pete Townshend interview, South Bank show, November 1985

I wanted quite simply to make a music piece, a musical teleplay. I wanted to allow a song cycle to evolve at the same rate as the story, at the same speed as the story, at the same rate as a film script. To have all the elements evolve together, rather than the normal musical form, which is you write a song, then somebody makes a video film of it afterwards.

Pete Townshend interview, Off The Record, 1985

In the film, the songs come in as comment in the story. On the album, in a poetic way, they tell the story. The album is not a film score. It’s got a couple of songs that aren’t even in the film. The film is just a 40 minute piece. It’s quite short, quite pithy. And the album is normal length. It’s not a concept album really.

Pete Townshend interview with Jools Holland, The Tube, October, 1985

I just made a film based on my album, which is called White City, and the films called White City. And I used an Australian director called Richard Lowenstein. It’s a short film, around 45 minutes, something like that. I’m really interested in films, like all we aging rock stars are interested in film, as a possible way out.

Pete Townshend interview with Robin Denselow, Guardian, November 1985

I intended the film to be a 24-hour walk around the area, set to music. It was to be a set of visual-poetic cameos and I hoped the music and images would say everything. I had a script, but it was very surreal. I saw it as a Nighthawks, Mean Streets kind of thing.

Pete Townshend, documentary for White City, The Music Movie, 1985

I started thinking about this particular film last May 1984. The original idea was simply going to be 24 hours in the life of somebody who spends a day literally wandering around that area. And by the end of the summer, around August or September, I completed a draft script of my own, and about 6 songs. In November I started recording.

What was interesting for me, and something that I was determined to do was to make sure that whatever happened to the story, whatever happened to the script, that the music would be allowed to evolve with that. And in fact it’s worked out very well. When I first met our director last year, we stripped away quite a lot. We stripped away a lot of the music we thought was superfluous. And the whole thing did evolve, you know, small steps. I did a bit of recording, and then we did together a bit of writing for the screenplay. We were inching forward, step by step. I’ve learned working with Richard, the director, that he has a role very similar to a record producer for me. I need a record producer because I need somebody to bounce performances off. The producer in a studio has a tremendous technical role. But he also is the public, he has to pretend to be the public. We have to attempt to move forward together. It’s very similar to recording, where what you’re attempting to achieve is a cataclysm really.

Pete Townshend Author’s note, White City teleplay, Eel Pie website, January 2002

The White City ‘teleplay’ was written over a period of several months in the summer of 1984 and was still a work-in progress. I was working as an editor at Faber and Faber in London at the time, and one of my colleagues there was the film producer Walter Donahue who had worked with Peter Greenaway, Wim Wenders and others. I asked him to help me make a film to serve as the dramatic backdrop to a new solo recording project - the first I embarked on since leaving The Who a few years earlier. Donahue suggested the young Australian Richard Lowenstein as a possible director and collaborator to complete the script and make the film.

It is important for me to remember that, with members of my own studio team, I had already shot many hours of my own location reconnaissance video movies of the White City Estate. Very early in that work I began to build up a sense of an irony at the heart of the place. The nationalistic images of Empire sparked by the historical street and building names jarred against the main political issue of the day, which was the dismantling of Apartheid in South Africa.

I wrote this teleplay during a period of personal struggle. I was trying to rebuild myself and a marriage damaged by drug and alcohol abuse. Through therapy, as a part of my treatment at the time, I had come to realise that I had been quite seriously emotionally abused as a child. Like many other celebrities - as I grew up - I turned to creative work and finally incomprehensible self-destruction as a means to draw attention to my subconscious difficulty. Writing White City was - for me in therapy - a way of facing some of the anger I felt towards the adults in my childhood, who had done their best, but failed to be perfect parents (if there can be such a thing). In the past I had allowed myself to rely too much on my creative work, the loyalty of my fans and the well-charted escapist avenues of show-business.

As ever, I found a cathartic creative system in my childhood neighbourhood. (Or in this case, in the White City Estate, a reality-based metaphor for neighbourhood). The ‘neighbourhood’ reflects for me the liberating business of rock 'n' roll. I grew up in neighbourhood bands. When I began to write songs I could better see my own problems by reflecting the problems of my neighbourhood audience, and that audience could better articulate their own problems by listening to my songs. So as I revisited my metaphorical neighbourhood, and looked down from my celebrity psychohelicopter at the younger Jimmy, and explored the resentment, anger, fantasy and harsh realities I could see in him, I found several characters who were all facets of a single mind that was not entirely my own. Clear reflections happened in two directions. The courage to face these faces, and listen to what they each had to say, became the single driving motive for me to make the film. Many of the songs needed images, many of the images needed poetry.

So there were several strands to bring together. One was the idea that the failing of Empire was what had defined and forewarned the desolation and decadence of my generation - rather than some ungrateful and sullen resentment towards those selfless and heroic souls who had fought or died in the war against Fascism. Another was that in a strongly Feminist climate of the '80s, men were increasingly being made conscious that without wars to fight they must struggle ever harder for some kind of male validity - and had to learn to face that their inbred machismo and violence were unacceptable and abhorrent. Another was that in my experience it had been women who had apparently caused most of my childhood suffering - the men involved were culpable of course but visibly absent. Another was that male sexual identity problems and gender distortions were manifesting powerfully during the late '70s and early '80s - and in some way I experienced triggered identification with those young men who wanted to defy macho conventions of the post-military epoch and dressed and acted effeminately.

Lowenstein incorporated into his own script many of the stronger conventional elements of my own, and honed together a solid story that - with more money and more screen time - would have made an impressive and moving major feature film with substantial music sequences. With a bigger budget I believe Lowenstein would have made a film for me that provided a British complement to Purple Rain. As it was, we shot on 35mm rather than the first proposed Super 16 and ran out of money and movie stock with about twenty minutes of film for music video still to shoot. (He had been charged by the record company part of the investors to produce three usable music videos within the story, and I think this too distracted from his ability to produce what would otherwise have been a far more conventional and satisfying full-length movie).

My daily involvement in the film as an actor meant that several pieces of music intended to be in the sound-track weren't even completed in the recording studio prior to filming. Two quite important songs, After The Fire and All Shall Be Well, emerged from the White City song-writing demo sessions but were never completed at the time. The first I gave later to Roger Daltrey to use on one of his solo albums, the second I adapted as a pivotal closing celebration in my next project The Iron Man.

I remember working on White City with great pleasure. I had never heard of Frances Barber (who played ALICE) when Lowenstein said he wished to cast her, but I now know what an important and versatile actress she is. It was the first time I ever had to sit with an actress and pretend to have feelings for her; I just felt - and looked - shy. Andrew Wylde really immersed himself in the role and worked hard to find the character of JIM. There is a scene in the film where he and I tell each other stories, and I found that much easier to negotiate. The rest of my 'acting' was confined to wandering around the White City Estate in a Metropolis-label overcoat. Lowenstein was really wonderful to work with once filming started, and we have remained friends.

I have to now admit full responsibility for being a little off my head at the time. When I am involved in a creative project of this nature I obviously tend to delve deeply into my private psyche for images and ideas. This project was no different. I had just finished working on a book of short stories called Horse's Neck using a similar process. It is one that is perhaps more familiar to the songwriter than the writer of fiction or screenplay.

So this teleplay of White City could not be made into a movie. My intention is not to present my collaboration with Lowenstein as reductive. I badly needed help from Lowenstein. In the U.K. in 1984 no one knew whether I was a distinguished publisher, a reformed junkie, a writer of short stories or a rock star. I was trying to do too many things at once, possibly in a confused battle for some meaning in my post-Who life. In any case, what should have been a deep and resonant 'musical teleplay' to rival Purple Rain became instead an anachronism - too short for cinema release, too long for music video TV, and too insubstantial for my more intelligent and incisive fans.

Pete Townshend, Who I Am autobiography, 2012

A few months earlier Eric Clapton and I attended a screening of Prince’s film Purple Rain. I was inspired by the way Prince had folded autobiographical references so elegantly into his film. I decided to create a film of my own, combining street scenes from a London district north of Shepherds Bush and music sequences. Walter Donahue, an editor at Faber working on the film list, recommended that we also screen a film called Strikebound, directed by a young Australian called Richard Lowenstein, whom I would eventually approach to direct my next project, White City. I imagined the narrative would be carried by images, and the words would be lyrical, almost an inner dialogue. The story I wrote worked for me, but not for Richard Lowenstein. He read my script, interviewed me and then presented me with a revised treatment that incorporated my answers.

The narrator was Pete Townshend the rock star, who has returned to his home town and is talking about his young friend Jimmy. Almost every traumatic moment in my childhood was included, although I’d originally wanted a musical play about my neighborhood, my family, my friends and the people I was coming into contact with in my new life in the mid-Eighties. Richard hadn’t followed all of my suggestions, but he put together a very tight shooting script, and I finally approved it. I was used to this happening. With every conceptual music project I’d ever worked on I allowed the ideas to come into focus by osmosis rather than through advance preparation. In most cases (Lifehouse being the exception) it had worked. This time the artwork, paintings, drawings and long tracts of writing I’d done were all subsumed in the film.

I wanted White City to be entertaining and colourful as well as real, and although Purple Rain indicated how that might be achieved it offered no clear blueprint. Prince, as an artist, was deliberately romantic and distant – he offered a pathway to his inner self only through his music. In White City the swimming-pool scene with its synchronised swimming sequences, and the fundraising show for the local women’s refuge, were intended to be entertaining while contributing to the central themes.

Pete Townshend interview, French TV, 1985

My work on projects like Tommy and Quadrophenia, which had began as records and then became films later on, have been quite frustrating for me. I wanted to work on a project where the idea for film or video and the music grew at the same time and same speed. I think music video right now is in transitionary form. Right now I feel I have to have a film and a record. One day, perhaps for my next project, it would be wonderful just to put out a video only. I think the cinema is finished, I think that rock concerts are finished. I think they will go on for a little bit longer, but I think as valuable art forms for a creative musician and writer, I think they are archaic, anachronistic, they’re tiresome, and they are doomed. And I think the real excitement for me lies in the abstract symbiosis, like a synergy between music and images, which can between them somehow create poetry, and that’s what I’m really excited about. But right now it’s really hard to do that because if I just release my music on the video tape, not many people would hear it. There isn’t a proper established market place for it. But I do think in the next 5 years, the market place will explode. And I think you’ll see musicians both using the format for selections of rock promos or cameo songs in the way that we’re used to already on television. But I think you’ll see a lot of musicians suddenly seeing that they can go a bit further, their song writing technique can be challenged and expanded, and increased in scope.

Pete Townshend interview, October 2005 (published in petetownshend.com Diaries, 2006)

I had hoped for a full length feature film rather than the long-form video we ended up with. I am pleased with what we achieved, but the original story was less about me as a rock star than a group of people I’d met in connection with the work of Erin Pizzey who founded the first Women’s Refuge (from male domestic violence) in London, and who The Who had started their charity Double-O to help. As the script changes evolved I became more the subject of the movie rather than simply the writer-composer. I think Ray Davies had more success with this kind of crossing over, partly because he had the courage to direct his own films.

This album is based on a story that I would very much like to novelise at some point. It touches on so many areas of the kind of world in which I grew up that it seems a shame to have it fail to properly flower. But in all these projects, in which I attempt to make a series of songs do more than usual, are experimental in nature and can fail for all kinds of reasons. The film may not have landed properly but many fans of my solo work cite White City as their favourite of mine.

The White City album

Songs

Give Blood

Brilliant Blues

Face the Face

Hiding Out

Secondhand Love

Crashing By Design

I Am Secure

White City Fighting

Come to Mama

Musicians

Pete Townshend (vocals, guitar)

David Gilmour (guitar on Give Blood and White City Fighting)

John "Rabbit" Bundrick (keyboards)

Steve Barnacle, Tony Butler, Phil Chen, Chucho Merchan, Pino Palladino (bass guitar)

Mark Brzezicki, Simon Phillips, Clem Burke (drums)

Peter Hope-Evans (harmonica)

Kick Horns: Simon Clarke, Roddy Lorimer, Dave Sanders, Tim Sanders, Peter Thoms (brass instruments)

Emma Townshend, Jackie Challenor, Mae McKenna, Lorenza Johnson (backing vocals)

Ewan Stewart (recitation)

Pete Townshend interview, Rockline radio, 1985

Everything I write has got something to do with me. When you write, you just draw from your own experience. I think Crashing By Design is very autobiographical, but not Give Blood. Give Blood is much more of a global song. It’s an appeal, in a way, that we shouldn’t be over ready to throw ourselves either into war or into street fights or any kind of violent confrontation, because it’s worthless and it’s futile. I think it’s something that obviously we men folk suffer from. That’s why in the song I close it by saying “Give love and keep blood between brothers”. I think traditionally in America, one of the wonderful things we inherited from the American Indian was the idea that blood was something that only passed between brothers. And in fact blood was something that cemented brotherhood. The song is really just an appeal really. Crashing By Design is actually quite clear I think. It’s about how I feel that you really do make your own destiny.

Pete Townshend interview, NBC Entertainment, White City album party, 1985

Give Blood has nothing to do with my career in rock and roll. It’s got nothing to do with playing the guitar, or the fact that my hands used to bleed. You ask anybody, it’s two days away now from Remembrance Day. You ask a few of the guys who fought in Viet Nam. They’ll tell you what the lyrics are about. The song is not anti-war, I don’t think the prospect of war is much of a problem these days. The idea behind the thing was actually to both honour the old values, the idea that somebody would be prepared to fight for something that they believed in. But to face the fact that that won’t work anymore, and that we have to find a new way of giving blood, of proving that we are capable of self sacrifice. It seems to me that the way that we’re confronted with now is just to make some kind of sacrifice for the people that we live along side. We can’t really hope to gain heroism through acts of valor abroad anymore. It just doesn’t seem to work that way. I think really the idea was also to keep blood between brothers. You can still shed blood, but do it [makes slit noise] wrist to wrist.

Pete Townshend liner notes, The Best of Pete Townshend, 1996

A lot of the White City tracks were done in very simple form. Give Blood was one of the tracks I didn’t even play on. I brought in Simon Phillips, Pino Palladino and Dave Gilmour simply because I wanted to see my three favourite musicians of the time playing on something, and in fact, I didn’t have a song for them to work on, and sat down very, very quickly and rifled through a box of stuff, said to Dave, “Do one of those kind of ricky-ticky-ricky-ticky things, and I’ll shout ‘Give blood!’ in the microphone every five minutes and let’s see what happens.” And that’s what happened. Then I constructed the song around what they did.

Brilliant Blues is a song I wrote dedicated to a Liverpudlian performer called Pete Wylie, who I like a lot. I particularly like Liverpudlian performers because when they get big in England, they stay in Liverpool. They don’t leave, and I kind of admire that, sticking to your ground. There was a picture of him on the front of one of the English newspapers, the NME I think, and he used to wear a sailors hat, and I just had this idea that the whole statement that the Liverpudlian performers were making by staying in Liverpool was renouncing this true blue British way, which was ok, the government in power and all that. We have two colours in Britain. Blue for the right, and red for the left. So it was quite simply just to say that the brilliant blue doesn’t flow in Merseyside. The Mersey is a gray neglected river, with a run down port, and a lot of problems in the area. When you go to Liverpool, they still got this incredible kind of Merseyside spirit.

Face the Face is a song about running, or people who have stopped running. It’s interesting, because after I had written it I discovered that T.S. Eliot, in a poem called Prufrock, had written a line which went, “We must prepare a face to meet the faces that we meet.” And in that line what he’s talking about is a kind of contrast to Dylan Thomas’s line, that thing of fighting death, rage against the dying of the light. He’s talking about preparing a certain dignity to meet your destiny. That’s really what this song is about. It’s both about preparing to meet whatever’s going to hit you, but also seeking it out. Seeking out, if not your, certainly not death, but certainly seeking your destiny.

Hiding Out is coming from the view point of one of the residents of White City. In fact, all the lyrics in a way are sort of monologues from different points of view. I feel that when people live in these tiny apartments with a TV set, which is their real window to the world. Because it’s like being in cells, the way people almost choose to live in very confined and personal private places. If you look at a place like Tokyo where there’s an enormous population, the spacing which people live get smaller, but there’s always the fact that you can always look out the window and see the stars. In fact, for somebody’s who’s in jail, just a tiny window, so you can see the sky, is all you need to keep you sane. It’s one of the great important things. That’s really what the song is about. I tried to get a kind of African feel to it, but I used a music computer, and it ended up feeling slightly more bouncy.

[I Am Secure contains the lyrics, “I am secure in this world of apartheid, this is my cell but it’s connected to starlight.”] The word apartheid is a Dutch word meaning literally living apart. I’ve always been very interested in the poignancy of the situation in South Africa, where black and white are not even allowed to make love. I wanted to use it in a poetic way to look at the way people in modern urban areas are sort of kept apart by the conditions in which they live.

White City Fighting was written for David Gilmour. I did two songs for his solo album. We co-wrote and I gave him lyrics. This was one of them. He didn’t feel that he could include it on About Face, because he said to me something like “I don’t know what goes on in the White City,” he came from Hampshire or something. So I’m glad he didn’t use it because it turned out to the be the central track for the album.

Pete Townshend interview, Rockline radio, 1985

I wrote some lyrics for David Gilmour’s solo album called About Face early this year. One of the songs was called Love On The Air, and another song was called All Lovers Are Deranged. One other song that I gave him was a song called White City Fighting. And that was when the idea for the White City story was still a seed. He sent it back to me a said “Listen, I like the lyric, but I can’t use it. And I said, “Why not? It’s good.” And he said that he felt he couldn’t relate to it, and that it was something a bit personal going on. It reminded me a lot of what Roger often used to say when there was a song that he felt was something, ah, Roger would more or less sing a lot of songs I thought he wouldn’t sing, and other songs he would kind of give back to me, not because he felt that they weren’t Who songs, but because he just felt they were very special to me. And Dave did exactly the same thing. He said, “Listen, I’ve got a funny feeling that this is more your song than my song.” And I’m really glad that he gave it back to me, because it became a central song for the album. But it was one I gave to him for his album, must have been January or February of this year. He wrote the music for that song. I very rarely co-write songs so it’s a kind of buzz for me to be working with Dave Gilmour. I started to get a hell of a lot out of our relationship in the studio too, because he worked on quite a few tracks. Particularly, he produces that characteristic syncopated echo sound on Give Blood. That tikatikatika noise that always makes me think of “We don’t need no education,” that kind of sound. It’s very characteristic Dave Gilmour sound.

Pete Townshend liner notes, The Best of Pete Townshend, 1996

Face the Face was done on a new keyboard, which was a form of DX7, and I was very keen to get something very, very fast and upbeat knocked out, and I knocked out a few sections that I couldn’t play all together. I could play bits of it, but try and do it all together and it confounded me, so I did a bunch of building blocks and said to Rabbit, “I want forty of them” – this is a Mozart technique – “five of those, six of these, seven of those,” and he wrote it all out and played it to a drum loop that we got from a box, and that became the beginning of the track. This was very much a new age type of recording, and that’s why it sounds pretty modern, I think. Simon Phillips overdubbed the drums, we later overdubbed the brass, we overdubbed backing vocals, we overdubbed everything. It was all overdubbed onto Rabbit’s synthesiser playing.

About the title White City: A Novel

Pete Townshend interview, Off The Record, 1985

As a joke, I don’t know if it will backfire or not, I said to the guy who was doing the artwork, at the very last minute I said, “Actually, on the album cover, let’s put White City: A Novel” as a joke! Anyway, he did it! He actually put it on, so I’m quite interested to see what critics make of that. Because that’s really where the rock opera tag came from for Tommy, it was half a joke, which people took quite seriously. But I thought it would be quite funny, knowing me and my editor’s chair at Faber and Faber. Writing and putting a record out which I actually called a novel.

Pete Townshend interview, Rockline radio, 1985

The word novel in the title is a joke. It’s partly related to the idea of me being an author and connected to publishing and all that kind of stuff. I thought I would call my new record a novel. I thought if I could get away with rock opera, I could get away with calling my album a novel.

Pete Townshend interview, NBC Entertainment, White City album party, 1985

I suppose [I called the album a novel] because I think it is new. It’s a bit of a gag to address the fact that I’ve been working as a publisher lately. And that if I was going to make a record, a video movie, that I should call it a novel.

Pete Townshend interview with Kristine McKenna, Spin, 1986

[I refer to White City as a novel] because I’m mischievous. I do think that long-form music video is the novel of the future and that all art will one day exist in a technological realm. That’s my prediction of the week.