Tommy musicals

Over the years, Pete Townshend’s rock opera Tommy has enjoyed a variety of stage incarnations, beginning with the 1971 Seattle Opera production that featured Bette Midler as the Acid Queen. In 1972, Lou Reizner presented an all star orchestral production at the Rainbow Theatre in London that included Steve Winwood, Rod Stewart, Sandy Denny, Richie Havens, and Ringo Starr. The Reizner production was repeated in 1973 with a different cast that included David Essex, Vivian Stanshall, Marsha Hunt, and Jon Pertwee. The Who have toured their own concert versions of Tommy since the release of the album in 1969, including a twentieth anniversary reunion tour in 1989 that was highlighted by a special presentation in Los Angeles that featured a stellar cast of special guests such as Elton John, Phil Collins, Steve Winwood, Patti LaBelle, and Billy Idol.

In 1991, Pete Townshend collaborated with theatrical director Des McAnuff to write and produce a musical adaptation of Tommy, which opened at the La Jolla Playhouse in 1992, moved to the Saint James Theatre on Broadway in 1993, and had a revival at the Shaftsbury Theatre in the West End of London in 1996. The production has continued to flourish in regional tours throughout North America and Europe over the last 20 years. Des McAnuff is currently reuniting with the original 1993 production team to bring Tommy back to the stage at the Stratford Festival in Ontario, which is scheduled to run from May 4 to October 19, 2013. The following is the history of this ground breaking musical stage production of Tommy.

Written by: Pete Townshend

Directed by: Des McAnuff

Development: November 1991 – June 1992

Stage debut: July 9, 1992, Mandell Weiss Theatre, La Jolla Playhouse, San Diego, California

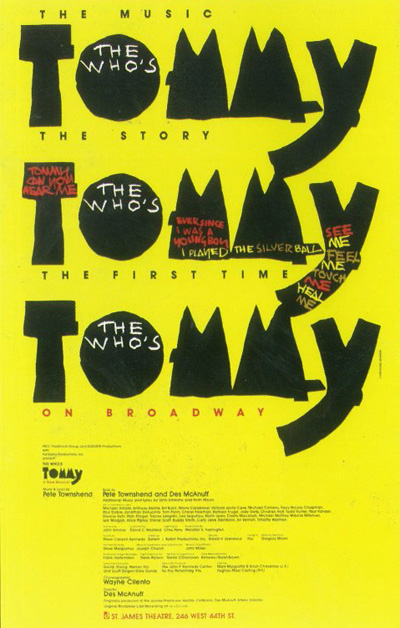

Broadway: Debuted on April 22, 1993, St James Theatre. Closed on June 17, 1995 after 899 performances.

West End: Debuted on March 5, 1996, Shaftesbury Theatre. Closed on February 8, 1997.

Awards

1993 Tony Award – Best Original Score - Pete Townshend

1993 Tony Award – Best Direction of a Musical - Des McAnuff

1993 Tony Award – Best Scenic Design - John Arnone

1993 Tony Award – Best Lighting Design - Chris Parry

1993 Tony Award – Best Choreography - Wayne Cilento

1993 Drama Desk Award - Outstanding Director of a Musical - Des McAnuff

1993 Drama Desk Award - Outstanding Lighting Design - Chris Parry

1993 Drama Desk Award - Outstanding Sound Design - Steve Canyon Kennedy

1997 Lawrence Olivier Award – Best Musical Revival

1997 Lawrence Olivier Award – Best Director - Des McAnuff

1997 Lawrence Olivier Award – Best Lighting Design - Chris Parry

Articles

Plot Synopsis

Interview with Pete Townshend in Los Angeles Times

Reviews

Musical Numbers

Overture - Ensemble

It's A Boy - First Officer, Second Officer, Nurses, Mrs. Walker

We've Won - Allied Soldiers, Walker

Twenty-One - Mrs. Walker, Lover, Walker

Amazing Journey - Narrator

Do You Think It's All Right? - Walker, Mrs. Walker

See Me, Feel Me - Narrator

Fiddle About - Uncle Ernie

Cousin Kevin - Cousin Kevin, Lads, Lasses

Sensation - Tommy

Eyesight to the Blind - Hawker

Acid Queen - Gypsy

Pinball Wizard - Cousin Kevin, First Local Lad, Second Local Lad, Lads, Lasses

There's A Doctor I've Found - Walker, Mrs. Walker

Go to the Mirror Boy - Specialist, Assistant, Ten-Year-Old Tommy, Mrs. Walker, Walker, Four-Year-Old Tommy, Tommy

Tommy, Can You Hear Me? - Cousin Kevin, Lads

I Believe My Own Eyes - Walker, Mrs. Walker

Smash the Mirror - Mrs. Walker

I'm Free - Tommy

Miracle Cure - Four Lads

Sensation (reprise) - Tommy, Reporters

I'm Free/ Pinball Wizard (reprise) - Tommy, Cousin Kevin, Guards

Tommy's Holiday Camp - Uncle Ernie

Sally Simpson - Cousin Kevin, Sally, Mr. Simpson, Mrs. Simpson, Guards, D.J., Tommy

Welcome - Tommy, Cousin Kevin, Guards, Company

We're Not Gonna Take It - Tommy, Guards, Reporters, Crowd

Finale - Tommy, Ten-Year-Old Tommy, Walker, Mrs. Walker, Uncle Ernie, Cousin Kevin, Company

Background Notes

In late 1991, Pete Townshend made an agreement with the PACE Theatrical Group to stage Tommy, in partnership with a group of theatrical producers known as Dodger Productions, one of whom was Des McAnuff, Tony award-winning director of California’s La Jolla Playhouse who ended up producing the work. “I wanted to be able to work with Pete,” McAnuff commented in the 1993 book The Who’s Tommy, co-authored by Townshend.

"Of course, I didn’t really expect him to say yes, but I immediately began to prepare. I listened to the original album, and the only decision I made firmly at that point was that I wanted to maintain real respect for the original recording. I wouldn’t want to update it or make it sound like a nineties version. I wanted to capture the sound and spirit of the original and treat it as a classical piece of rock-and-roll…"

McAnuff also wanted a more realistic Tommy than Russell’s rendition. “…we were not interested in exploring Tommy as a fantasy,” he wrote in American Theatre in 1993.

"We believed that the “Amazing Journey” described in the lyric was best achieved by grounding the members of Tommy’s family, the Walkers, on some kind of recognizable landscape. …Ken Russell… had in his 1974 motion picture already given us the fantasy extravaganza (which lives on as a prime example of that particular genre of filmmaking from the ‘70s) and we were more interested in exploring Tommy as a dramatic theatre piece."

Development began in November 1991. “From the moment I met Des in London,” Pete recalled in 1993, “I felt he was absolutely right. What struck me was that he understood the rock’n’roll ethic that underlays Tommy. He never let go of it. He’s always held on to the fact that the original songs are all a very important part of the spiritual quality of the piece.”

“We just talked and talked and talked and talked about the outline,” McAnuff said in 1993. “Pete had a lot of comments, and we switched some things around, and we talked philosophically about the piece. I think quite quickly in that five hours we also made the biggest decisions—the decision about having more than one Tommy [1]; the critical decision to keep Tommy a local hero for as long as possible, to keep that rise to power very brief; and the decision to create a story about a West London family and to ground it in some way—not to make it a fantasy or go in the direction that I think it’s gone in other versions.”

McAnuff explained the play’s timeline to American Theatre in 1993: “…Pete and I agreed that what we were dealing with was, in essence, a postwar story set against the background of historical events that led up to the 1960s, so the blitzkrieg of 1940 and the rock-and-roll British invasion of 1963 became the bookends for our timeline.”

“By Christmas we’d really made most of our decisions,” McAnuff wrote in The Who’s Tommy. “We’d pitched the song order back and forth by fax… What we did was tell each other the story, more or less. We would walk through each act, scene by scene, and I would describe some of the visual work that I thought we could do, and Pete would talk about philosophy and then we would discuss themes and characters.”

“…there were substantial gaps in the story line that needed to be addressed in order to realize a full theatrical presentation of the piece,” McAnuff wrote in American Theatre.

The delicacy of the original story – about a traumatized youngster who rises to pop stardom as a deaf, dumb and blind pinball virtuoso – was one of the concept album’s great strengths. It inspired a willing audience to fill in its own personal detail, and the ambiguities and puzzles that the album served up were consistent with Pete’s ambitions to create a spiritual journey. We wanted very badly to preserve the strength of the original recording. At the same time, in order to produce a viable theatre piece, we needed to flesh out and expand the original.

A key piece of Tommy which needed attention was the ending. “…I have learned there is a vital difference between the simple rock song and the conventional music theatre play – that it’s necessary to bring a story to a conclusion, something you never have to do in rock-and-roll,” Pete wrote in The Who’s Tommy. “When I originally created Tommy, I did it with the understanding that people of the time were exploring the limits of their imaginations,” Pete told the San Jose Mercury News in July 1994.

"They were in pursuit of spiritual awakening. When they sat down to listen to Tommy with a joint in hand or whatever, they were saying to themselves – and probably to me – ‘We want to go somewhere.’ And I specifically left parts of the story open to allow them to reflect and review.

But with this version of Tommy I approached it from the point of view of the dramatist. Onstage, you have to tie things up in a sense. And I did tie it up at the end. But I didn’t add anything that wasn’t there to begin with."

Pete was referring to the rewritten ending during which Tommy reunites with his family, embracing each of them, including Cousin Kevin and Uncle Ernie. Together, Tommy and family sing Listening To You. Many observers were critical of this ending due to its ‘happily ever after’ implication. “We’ve had people come away thinking it’s a Nancy Reagan ‘family values’ message,” Pete told the New York Daily News in July, 1993. “We’d like to make it clear that it’s not.” Indeed, Pete told the L.A. Daily News in 1994 that Tommy’s return to his family could be for other than benign reasons. He suggested that the reunion may have initially occurred for Tommy “to wreak vengeance. Tommy’s embrace of Uncle Ernie is immensely cruel. …You think, ‘What’s he up to? He’s obviously about to embark on retribution.” But he snaps out of it. “He ends up accepting who he is, what he is, what he’s been through. And (he accepts) the people around him.”

Other adjustments drew additional criticism, including the insertion of the line freedom tastes of normality (as opposed to the original freedom tastes of reality) in I’m Free, and the removal of many religious references. For example, the ‘kids’ rather than ‘disciples’ lead Tommy in in Pinball Wizard, and the revised Amazing Journey disposes of the mysticism of the original. The ‘tall stranger’ with ‘silver sparkled glittering gown whose golden beard flows nearly down to the ground’ is removed, replaced with a description of Tommy himself. Another target for those who complained that the Broadway Tommy was too soft was the Acid Queen sequence: Tommy’s father whisks him away before she has a chance to begin her peculiar brand of therapy.

“It was clear I couldn’t compete with the acid trip someone had when they first listened to the album,” McAnuff told the Washington Post’s Lisa Leff in December, 1994. “All I could do was carry out Pete’s vision and my own vision of the piece. There was really no other choice. I knew we would take some lumps from people who had a very strong personal relationship with Tommy. But as it turns out there has been far less of that than I ever would have expected.”

To facilitate the parental decision-making which must have taken place between Tommy Can You Hear Me and Smash The Mirror, Pete wrote a new song, I Believe My Own Eyes. The song was “…a conventional music-theatre number in many respects,” Pete wrote in 1993.

"…It has a job to do. It has to suggest the passing of time and patience and must strengthen the audience’s feeling that the parents are exhausted but still young enough at heart to hope for their relationship. It also must keep the audience’s focus on the mirror, about to be smashed by the mother. And it has to attend to the idea that when there are no answers we have to look inside.

There was one other, less specific, part of the brief – and that was that we wanted a ballad, something like Behind Blue Eyes from the Who. I trawled all these elements together and came up with the song. By doing so, I surprised myself and everyone else. It is not as popular a song in the show as I had hoped, but it is vital and it works. It is the one piece of new writing I have done for the show that makes me feel I can really write music drama in the future."

“Tommy is a spiritual journey,” Townshend said, explaining that Tommy’s disabilities are metaphors for the deafness, muteness and blindness “that we live in as far as spiritual matters are concerned…We’re super-efficient intellectually, super-efficient physically, super-efficient in all kinds of ways, but spiritually we’re driving blind. We don’t know when we’re making progress and when we’re not.”

Once Pete and Des had hashed out their onstage rendition of Tommy with “a fair bit of detail” according to McAnuff, the work began for the La Jolla Playhouse staff to bring the work to life. In addition to its 24 actors, the show would feature nine rear-projection screens to aid in visual presentation (this number increased to eighteen when the show went to Broadway), a nearly full-size airplane out of which actors ‘parachuted’, a huge pinball machine (one of nine custom-built machines used in the show), dozens of television monitors which showed footage filmed live from the stage, and eight tons of scenery. On average, costume changes took place every three minutes, as cast members donned one of over 1,000 costumes which were made for the show, one of which was a $3,000 white leather jacket.

Pete’s involvement with the adaptation of Tommy’s music to the stage show was seemingly not as extensive as one might imagine of the man who composed the original piece. He reportedly wasn’t involved in choosing the seven-member band (two guitarists, bass, French horn, drums, two keyboards), nor did he meet them until two weeks prior to the show’s premiere July 9th.

Tommy onstage proved a huge success, enjoying a Broadway run of more than two years.

“I wasn’t surprised, when I first saw it, as much as I was relieved,” Pete told the San Jose Mercury News in July 1994 of his reaction to the first show. “I thought, finally someone has done what they said they would do. I had worked with a number of people in the past… but Des made good on his promises.”

[1] “Considering his total isolation in most of the story, how were we to find an emotional throughline for the character of Tommy?”, McAnuff told the Washington Post’s Lisa Leff in 1994. “The basic conflict in the story , we agreed, was between Tommy and Tommy. This gave birth to the idea of the multiple Tommys (i.e., Tommy at 4, Tommy at 10 and the adult Tommy – our narrator). It was the interaction between these characters that created the magical layer which led to many of the most exotic visual elements in the production.”

Background Notes by Mark Wilkerson.

Merchandise

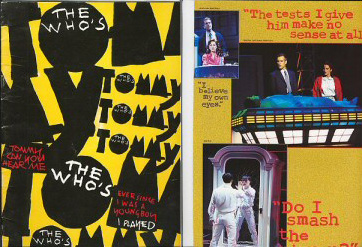

Program

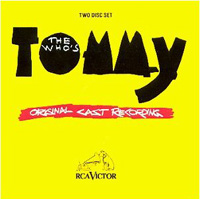

Original Cast Recording produced by George Martin

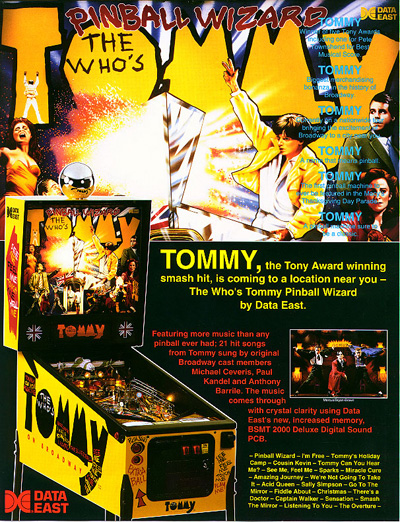

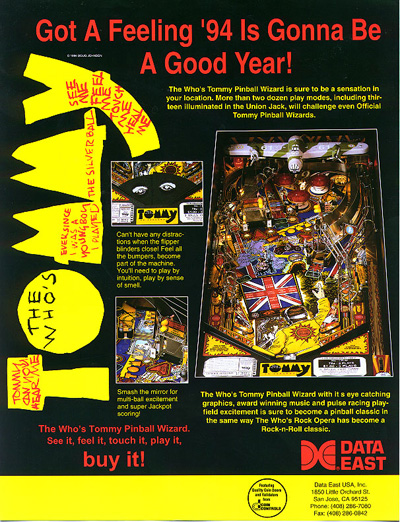

Pinball Machine

Poster