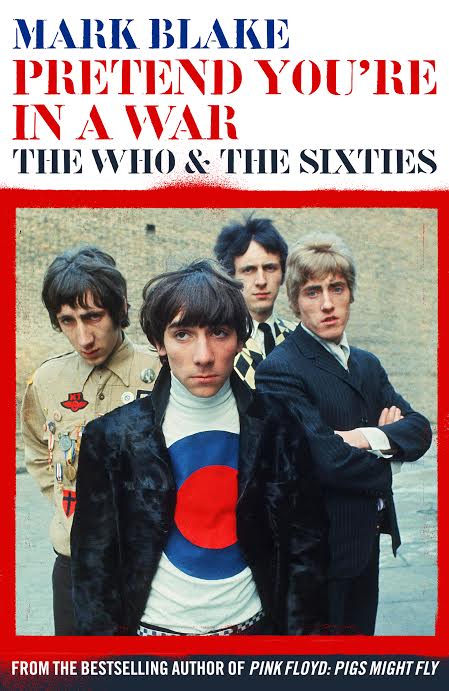

To research his excellent new book PRETEND YOU’RE IN A WAR: THE WHO & THE SIXTIES, author Mark Blake interviewed nearly 100 key characters from Who history, including ex-bandmates, schoolmates, producers, girlfriends, roadies, and friends of the band and their management team. Mark left no stone unturned, and the result is an impressively detailed account of the formative years of The Who leading up to the end of the sixties, including the history of the bands families and their managers Lambert and Stamp.

This is a MUST READ book for any fan of Pete Townshend, as well as anyone interested in one of the most important periods of music and culture in history. It is available now in the UK, with a US release set for the new year.

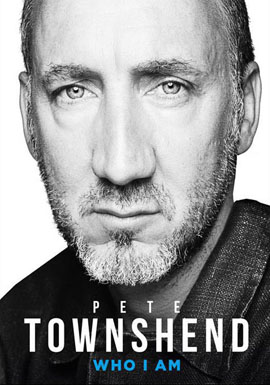

Mark Blake has started a new blog at markrblake.com, where he plans to post a few of his interviews in the upcoming months. To start with, he has posted an extended interview with Pete Townshend that he did for Mojo magazine in 2012. Pete was plugging his excellent autobiography, Who I Am, which is covered thoroughly in this interview.

Mark was kind enough to let us repost Pete's interview here. Be sure to read the interview we did with Mark back in Sept too. Enjoy!

Pete Townshend won’t shut up

By Mark Blake

In September 2012, Pete Townshend talked to me about his post-war childhood, Shepherd’s Bush villains, punching his ex-manager, how The Who helped invent the Sex Pistols, gay British Rail guards, Mick Jagger’s penis… and much more.

This is a much longer version of an interview that ran in Mojo magazine in December 2012. It took place at Pete Townshend’s offices in Richmond, Southwest London, just before publication of his autobiography, Who I Am. There’s a lot here about Townshend’s arrest, his book and the Who’s plans to tour Quadrophenia, which happened the following year. But there’s also a lot about the Who’s early years that I used in my book, Pretend You’re In A War: The Who And The Sixties.

Pete was on good form. He talked and talked and talked… Even when I hit the ‘pause’ button and we had a quick tea break, he carried on talking (about Phil Collins, freemasonry and the police force, if I recall). In fact, Townshend was still talking when his PR started waving his hands and telling us the writer from The Guardian was due in ten minutes and it was time to finish.

It’s always good when you can’t get an interviewee to shut up…

Is it true you first wanted to write an autobiography when you were twenty?

Yes. But the book I talk about wanting to write when I was twenty would have been a very different book to this one. I wanted to write about what was happening to when The Who were very young. What happened when The Who first started and around the time of [first single] I Can’t Explain was that I realised the need to talk about the function of the song and pop music. Pop hadn’t become rock yet – it was still fairly simple stuff. But I knew because of my background with my dad who was in a dance band [The Squadronaires] that something had changed in quite a dramatic way. What was interesting to me was to look back and imagine what that book would have been about. Because a lot of it was going to be about The Who’s fans, the way they perceived us. I also wanted to write about the readers of [defunct music mag] Disc & Music Echo fans, and the journalist Penny Valentine.

Penny Valentine was a big advocate of The Who’s music in the early days.

Yes, a word about Penny – she started off writing in that fan way but then became an incredibly serious music journalist, and became the first person to write a confessional about suffering from depression. In that, she talked about a night getting drunk in my flat in Wardour Street, not with me but with her then boyfriend Ray Tolliday who shared a flat with me. So I wanted to write about Penny and fans, particularly female fans and how they would get so upset if they found out you had a girlfriend.

But you didn’t revisit the book idea again until the mid-‘90s?

The Who finished – in my eyes, at least – in 1982 when I left. We didn’t tour for a time. But then I started to think about my solo career, which didn’t so much run out of steam as disperse. I got into a thing – which I have seen happen with very few other artists, perhaps Brian Eno – of my solo career dispersing into loads and loads of other projects. So my energies were dispersed.

So I thought the thing to do was to write a book about art, music, and the post-war scene – almost a sociological thing. So I started in earnest in 1993, and about a third of what’s in the book now came from that. Not much survived, and when I came back to it again, it was in 2005, and I did a whole batch of writing, and then I put it down again, and then this time I decided I just had to do it.

And then you started for the final time…

Yes. This time I decided I just had to do it. It was nothing to do with my arrest. Because I could have just done a piece about that with a newspaper and controlled the facts, but the thing about the arrest was that was what made me want to draw my story right up to the present day – which meant there was a bit of groundhog day going on. I’m like a cracked vinyl record – post-war post-war post-war. Younger people must wonder what the fuck I’m talking about [laughing].

I’ve heard that the book was originally much bigger than the published version. How much was lost?

The book was brutally edited. Oh, it was bigger. It’s big now, almost too big. The last editing job we did we cut a thousand pages to five hundred, and you can see that because there are these strange conjunctures. Before I wrote it like a story, a narrative, no jumps. It just flowed. But what happened was my editors, particularly at my American publishers, kept saying to me, “This is not fiction. People are not sitting back reading a book. They want to be carried through. You need to pick up the pace.” I think the book is better for it. But there is quite a lot missing.

The book was brutally edited. Oh, it was bigger. It’s big now, almost too big. The last editing job we did we cut a thousand pages to five hundred, and you can see that because there are these strange conjunctures. Before I wrote it like a story, a narrative, no jumps. It just flowed. But what happened was my editors, particularly at my American publishers, kept saying to me, “This is not fiction. People are not sitting back reading a book. They want to be carried through. You need to pick up the pace.” I think the book is better for it. But there is quite a lot missing.

How did Roger Daltrey and your ex-wife, Karen [Astley] feel about the book?

Both those two people you have mentioned didn’t want me to write the book. I think they had copies before it was published. But neither of them had read it, I don’t think. It might be they came out of it well simply because they are still alive, and what I don’t want to do is cause them pain. But I also think that I am honest about them.

There might have been a few things I could have said about my ex wife and about Roger that would have made things a lot worse [laughing]. But that’s not the purpose of it. It was handy that a few people like Kit Lambert and Keith Moon and John Entwistle are dead because I just felt I could write freely.

How do you think Kit, Keith and John come across?

I think what happens with Keith is you get a good sense that he drove me barmy, but that I loved him to bits at the same time. And the same with Kit Lambert. He drove me to distraction but even as I am punching him in the face during the making of Quadrophenia, I loved him. Of course John was much easier to love, as he was no trouble. In a sense, being able to write about people honestly, does lead you to getting a better fix on them.

How about your relationship with Roger?

With Roger what I have been trying to deal with is that our relationship has been mythologised a bit. There is only one thing that has been wrong with my relationship with Roger Daltrey, and that is that I’m not very good at co-writing with anyone and Roger is not very good at writing songs period. But that’s not to say that he doesn’t have tremendously good ideas. So for years and years he’s been carrying all these ideas and doesn’t have anywhere to put them, but instead he’s always having to deliver my sometimes quite tricky, audacious and sometimes very pretentious and silly ideas. And it has created tension.

Has the relationship between the two of you been portrayed as more violent than it was?

Yes. The only time it came to a physical head was around the time of Quadrophenia. Which for both of us was a triumph. The time when he knocked me out was while we were rehearsing for Quadrophenia. It was my fault, not his. But it came from exhaustion not from anger.

When you’re writing about your childhood, it seems that you were a little kid sometimes adrift in a very adult environment.

Yes, one of the thing’s that affected me about being on my dad’s band bus at that young age was the celebration of alcohol. There were also a couple of guys on the bus in latter years and you would smell the funny Jamaican weed coming down the bus.

It does seem like a glamorous world, though: travelling with your dad’s band and watching them play?

Yes, and the other thing that suggests glamour is that there were Americans everywhere. It’s not that we’ve forgotten that but we have mythologised that. There was this scenario where my mum and dad would take me round to see one of their fabulous American officer mates and we would sit in their fabulous house with their fabulous car outside, and there would be loads of money and food about, and they’d have food we didn’t have – like sugar.

There’s violence as well, though.

As I got a bit older, eight, nine, ten and eleven I had this sense of being in these romantic ballrooms where beautiful young women were dancing. But where men who would be, like “Can I have the pleasure of this dance?” one minute and then the next pulling out this blade and trying to hack someone to death. When I got a bit older, nine or ten at the Palace Ballroom in the Isle Of Man, a policeman was murdered in front of me. He was a motorcycle rider and a fight had broken out. He didn’t die on the spot. He died subsequently after being kicked to death. This was in 1950-something.

There would be Scottish week, Northern Irish week, Liverpool week and Welsh week at the Palace Ballroom and it was when they intercepted that the trouble would start: “We’re talking over now Jimmy!” – and it would kick off. The girls would run away screaming, and the Palace Ballroom was massive with a bouncing floor, which would bounce as the fighting started, but the band wouldn’t stop. They kept playing. And later The Who wouldn’t stop either when it kicked off. Roger would jump in to the crowd, kick off, and then get back on the stage and finish the song.

The book also addresses the possibly sexual abuse you experienced as a child. How difficult was it to write about that?

I think for one of the things that has been so strange is to have such extraordinarily vivid early memories of my childhood which stop within a few weeks of being sent to stay with my [maternal] grandmother Denny [Emma Dennis]. When I first went to stay with her I was about four and a half, and I quite enjoyed it, which is why I thought my mother [Betty] thought it would be OK to send me to live with her later when she was going nuts. It does seem extraordinary.

The thing was I was still very young. Between five-and-a-half and a month I turned seven [May 1952] because in June I was back in school in Acton, I completely blacked out. But I know a lot of what went on. What happened in the 80s was I went into therapy for no other reason that I had stopped drinking and using drugs, and I just wanted to stay on my own case. I didn’t want to hang out in groups with people telling me how wonderful I was for staying sober, but I thought it would be good for me as an artist. And I did it for three years, and at the end I sat down and wrote. I remembered a lot but I couldn’t put the bits together. But then I went and worked in groups [for survivors of childhood abuse] and sometimes guys in the groups would take me aside and say, “I was abused. I am older than you. But I was shipped out in the middle of the war to Wales and the guy that ran the farm was a Nazi, who believed the Germans were going to take over and he just had his way with all of us – boys and girls. And after the war we were shipped home and I said, ‘Dad, Dad, that farmer…’ And he said, ‘Shut it! He saved your fucking life! That’s what he did – so shut it! You didn’t hear it. You didn’t see it.” So that’s where the words ‘See Me, Feel Me, Touch Me’ [on The Who’s Tommy] come from. Listen, I’m not trying to ring a tear out of people’s hearts, but that’s where the writing came from.

There’s also the fact that a woman was involved in this abuse, which will surprise people.

The abuse I suffered from my grandmother that I do remember was the physical brutality. The punishments, being shut away in the metaphorical cupboard under the stairs – that kind of thing. But also the lascivious underlying sense of bizarre smutty eroticism there was around her life. The fact that she would pursue handsome US serviceman trying to get something from them. I could never work out what we got.

She was horrible to me, she would punish me by not giving me food, she tried to drown me in the bath, she had these weird blokes to stay who would bounce me on their fucking knee. Let’s get this in perspective. I am not that much of a little boy. I am six years old. You don’t bounce a six-year-old on your knee if you are a ‘distant uncle’ – in inverted commas. The whole thing was so strange. I was terrified. I lived in constant fear. She did this other thing of these unbelievable forced marches. She would wake up at four o’clock in the morning and then get me up and at five we would start to walk all the way from Westgate to Manston Airport just to meet some fucking US officer.

Can you tell us more about how you came to remember some of this abuse?

When I finally did the thing of trying to regress myself, the body chemistry gave it away, because I just started shaking. That’s the indicator. You start to realise that your head can say one thing, your heart can tell you another, but when you start to shake it’s a clear sign of anxiety that something happened.

That’s when people who’d experienced abuse, took me aside and said, “Pete, I think, it’s clear that you’re one of us.” And the term used for survivors of childhood sexual abuse is we call ourselves brothers and sisters. So that if I ever meet that guy, It’s “Hey, brother.” So you know. But we don’t have to talk about the details [of the abuse]. I don’t remember, but if I did I might pretend not to remember. I am not trying to do a double bluff here. I promise. But I don’t want to excite other people – I don’t want to create fires I couldn’t put out.

What does it matter in a sense? The detail. Esther Rantzen has recently published a book for Childline with adults talking about the abuse they suffered as kids. But I just think, Fuck. Why do that? I think she’s got a good heart, and OK it is done now. But I don’t know that I want to know the details. I feel like I’m lucky that I don’t remember, because it has allowed me to approach this issue, though not consciously, but through my work, but to be able to own it.

Listen, this is not a good thing that happened to me but it was relatively brief, it didn’t last my whole life. But it has perfumed by work and allowed me to express something in my work that has resonated with Who fans, and continues to resonate. I went away and wrote a song called I’m A Boy, where I am a boy who is surrounded by girls and my mum dressed me up as a girl. A couple of blokes have come up and said, “That song saved my life.” They’re not saying, “Oh you used to dress up as a girl, didn’t you?” Because I didn’t. But that song came from somewhere in me that had an empathy with that viewpoint.

A Quick One While He’s Away [on The Who’s second album, A Quick One] actually touches on the subject of abuse. Was that really subconscious?

I was completely unaware of it at the time. My friend, Barney [Richard Barnes, Who biographer] would say A Quick One… was “the first mini opera and a silly story.” It is a load of rubbish and a silly story. But when I looked at it again it is a story that many of us post-war kids share of being sent away, of losing a precious loved one and being greatly changed when they returned.

A Quick One While He’s Away features a predatory train driver. In a BBC interview in 2011, you talked about kicking a train driver in the balls after he tried to abuse you on the train to Westgate?

[Laughing] Yes, I was put in the care of the guard. There was this tradition that a lot of the guys that worked for British Rail at this time were gay. It was a safe place to talk about being gay and you got to wear a uniform.

Going back to your mother’s response to what happened to you as a child, you said that her explanation for sending you away was “satisfactory”. Can you explain more?

I interviewed my mother about this for three days running, and she wouldn’t talk. And then she started to talk, but only about herself. And she talked about her mother leaving her father [for another man] and how she was left to look after her little brother, and how angry she was with her. What happened after a while was I said, “Your mother left you and then you sent me to live with her?” But then she would go to another place, “Oh yes, yes, yes, but your father was letting me down. He was away on the road so much…”

She didn’t go as far as to say, he was off shagging chorus girls but that could have been happening. I don’t get the sense that my dad would have done that. I did know that he had a girlfriend when my parents had split up for a bit. But prior to that I think my mother was screwed up. She found this man who was very rich. I think he was the head of the oil division in Aden, which would have been BP. He had shares in BP. Had a car, bizarrely a VW Beetle. I was about five or six at the time and he said to my mother, “I want you to divorce Cliff and I want you and Pete to come and join me in Aden.” But in the end she decided not to do that, she and my father got back together. But for a long time, all this stuff was going on which is how she justified me going to live with her mother.

You’ve talked about wanting to write a book about The Who’s fans as far back as the early 60s; you’ve talked about having a certain empathy with The Who’s fans. Do you think Who fans are different from other band’s fans?

There’s no point pretending that any of us are perfect. We all have a little bit that is vulnerable, a little bit that is shy, a little bit that is arrogant, a little bit that is a complete arsehole, and the rest that is just what we call human. We all have chunks of that stuff in different degrees. Some of us have one percent that is vulnerable; with some it’s twenty per cent. What has become clear to me is that The Who’s audience, the people that are really serious Who fans have a big chunk of a fucked-up personality – equal to my own.

Their response to things might not to be the same as mine. But what they like about us is that there’s wimpy little Townshend writing these vulnerable songs, but the guy who sings them, if you argue with him he’ll beat your brains out.

Is this something you learned from doing the book?

It made me think about our strange chemistry. In the early days of The Who, there’s the sense that we were also a gang, and we were cool. John had this profound stoicism and musicianship; Moon was a clown but very sought after by girls; Roger was very powerful, and I wrote the songs. I wouldn’t say they were songs from the heart but they were songs from the psyche. That’s the thing about doing this book; I’m kinda on my own. I am on my own with it. It feels weird not to have Roger there going [growling] “Don’t ask him a question about that.” That’s the thing, we do agree more then we ever did. With the other two guys not being there anymore, we now find the dynamic of the two of us easier to manage.

Let’s go back to the whole post-war thing in the book. There’s a lot here about what it was like being at school just after the war, and how that influenced your writing.

It wasn’t just a theme for me. Other people over the years would come up to me and go, “Ah, yes, you’re talking about what happened to us.” Humiliation was a part of the education system when I was growing up. There’s the guy writing on the blackboard and he’s got a blackboard rubber – which is a lump of wood – and a boy’s messing around and he shouts, “Wilson! Quiet!” Bang – the lump of wood hits the boy on the head and knocks him out – and the boy is carried out of the classroom. That happened!

And a boy is running in the corridor and is stopped and caned on the spot. It wasn’t so bad until the second year when they brought in girls [Townshend’s school Acton County Grammar, had previously been an all-boys school]. So the old guard were still doing all that stuff – and giving you a thick ear that made you cry out of shock, with tears all over your face. But now there was a group of girls looking at you while it happened.

Then again, I can remember Roger swanning back into my school, the one he’d been expelled from a year before, quite capable of beating to death any teacher that hit him with a blackboard rubber.

The abolition of National Service in the late ‘50s changed everything for your generation, though, didn’t it?

Yes, those of us born after the war was over, were never called up or asked to go and kill Germans or Vietnamese or go and kill anybody. But I remember at the time, this attitude from parents or grandparents – We were the ones who were told, ‘You are no use to this country or to anyone, just go out and enjoy the sugar, you’re lucky to have it.’

There’s an element to your story of wanting to be a part of the gang, whether that was at school, at art college or even in The Who.

I needed that. Was I looking for an older brother?….. Both my younger brothers [Simon and Paul] who were separated from me in age by some distance would say that I was a good older brother. Because I learned from that. I think it might not be so necessary now with the middle classes. But I think that if you come from the Whitton Estate it’s good to have someone on your side who is big and strong and has some influence. And that’s what we had. And that’s what I wanted to be. My neighbourhood, Acton, was not a terrifying neighbourhood, but we were close to places like Shepherd’s Bush and the White City estate which was murderous. There was a gypsy encampment under where The Westway is now. Reason it’s under there is because they wouldn’t fucking move when they built The Westway on top of them over their fucking heads – proper Romany guys.

I knew that what I wanted to do [in The Who] I couldn’t do unless I had a gang. Because I was a little Hitler, wasn’t I? So I needed my army. Because I wanted to go out there and say, ‘They’re all cunts! Hey, Winston Churchill is a bastard!’

So what you have got to do is find is a good bloke. A strong bloke. And if you can find the top man and become his lieutenant… It worked for me tremendously well as a young kid. In negotiation with boys in the gang, humiliation was a very important part of that too. It was the way gang leaders ran the gang. What they would do is to subjugate junior members of the gang is beat them up in full view of everyone else and then might take you aside after and say, “Nuffin’ personal”. This might all sound a bit Reggie Kray but it was happening on the Crane River estate. When I write about my childhood it is not to get a tear but to explain the context. And where it ended up was being told that the world was gonna end, a nuclear bomb would drop on us – not might – but would, so that sense of disenfranchisement was absolute.

The book addresses the impact of the atomic bomb on your life in the ‘50s and 60s. It’s easy to forget how permanent that threat was, even into the 1970s.

Yes. I was really angry from the age of eleven or twelve, growing up, because I had been told by really smart intelligent men that I became very friendly with later, like Michael Foot that the bomb was going to kill us. Years later, I said to him, ‘Michael, I remember you telling us in Trafalgar Square that we weren’t gonna survive, and here we are now. You’re eighty-five, I’m nearly fifty – where was the bomb that you promised me?’ He used to say, ‘Maybe because we threatened it, it didn’t happen.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, but you blighted my teenage years.’

This is what my new piece, Floss, is about. I don’t like the fact that the middle classes today are so doom-struck that they can accept that the Olympics was a wonderful, poetic event. And I’m not taking the piss, but it was. We all thought it was going to be a disaster. But everyone is now, like, Right, let’s just concentrate on the Islamic man that is going to blow us up, or the fact that we’re going to be poisoned or someone is going to steal all our money.’ There is this misery that we have created. There is no vision, no hope, no optimism. And I understand that people are having a hard time and I’m not financially speaking… But I was angry with those men, Michael Foot, Bertrand Russell and Victor Gollancz. He spelled it out, as I said in the book, “You will walk into the sea with pus running from your eyes” – I was twelve when I heard that!

Going back to your original idea for a book about the changing function of pop music – you were well placed to observe that change up close.

Yes, because I was in this world where as a child I was on the bus with my dad and his dance band. But when I was twelve or thirteen, suddenly there was skiffle, Elvis and Bill Haley. The first guitar I ever played was the one my mate Jimpy – Graham Beard’s – dad had made for him just so he could pose in front of the mirror. It was barely functional, but I got a tune out of it. This was 1955, 1956. Suddenly I’ve got this mankey homemade guitar. My dad is handsome, well-dressed and he wakes up in the morning and plays Prokofiev, he’s sophisticated, he drinks and all the women love him but I’ve got my guitar and I know I can point it at him and go, “Bang! You’re dead!” And I couldn’t even play it at that point.

Let’s talk about the part in Who I Am where you talk about “hearing angels” as a child: “Violins, cellos, horns, harps and voices… countless threads of an angelic choir.”

It might be an admission of some kind of aspect of bipolar. But I am able to go to a place where I can hear sound – not music and I don’t hear voices – but just sound.

Does it still happen?

Not as much, and I miss it. It subsided with age. I am certainly happier in my skin than when I was younger. When I was working on Baba O Riley I found this old organ and tried to make the same sound. I just about approached it. But it was nothing like as beautiful. I have never heard a piece of orchestral music that comes close.

When I worked on Iron Man later [in 1989] with Ted Hughes – he was the Poet Laureate at the time – I told him about it, and he called it ‘celestial music’. He told me, “Yes, it exists, it’s the music of the spheres.” And I said, “Well, I don’t want to call it that.”

You also mentioned trying to hear the same sound when you were singing in the church choir.

Yes, I became a bit religious, but my parents weren’t. I don’t know how that happened. They sent me to Sunday school probably so they could go to the pub or have sex. Then I graduated from Sunday School to the choir and I sang in the choir every weekend when I was at Acton. I don’t know if that made me religious. But I had this sense – I might be revising this because of my later discovery of Meher Baba and how he talks about every great spiritual messenger – that maybe because I had heard this stuff, that if I sang in church I might hear it again.

But later on, listening to all this, ‘Oh Jesus Christ, our lord’, there was something about all this ritual that made think its time had come. I had this sense that everything had become worn out, we needed new values, and much as loved that ‘Oh Jesus Christ our lord’ had come to save our souls and I loved being part of the flock, it felt to me like it was over. Like I was looking at the end of the show. The celestial music thing was important, because as much as I loved this choral music I was hearing in church, compared to what I heard in my head it came up wanting. I thought, What I hear is much better than this crap. That’s what made me want to start to compose.

Your father, Cliff, was a musician, but it doesn’t sound as if he encouraged you very much.

I probably took a pop at him with my crap guitar. It’s easy to say in hindsight. But the guitar replaced the sax as the sexy instrument of the late 20th century. I think the problem was that I didn’t play music in the way that he understood it. He was a classically trained clarinetist who played sax in a dance band and was over qualified for the job. He didn’t see any point in having a piano in the house because I showed no musical aptitude. He tried to teach me how to read music. I would kinda get it. I can do it now but as long as its simple. Rachel [Fuller, Townshend’s partner] can see a score and hear the brass parts. It’s not that my dad didn’t support me, just that he used to encourage me to be a writer, instead: ‘Be a journalist. That’s a good idea.’ Then when it was clear that I was good at painting he encouraged me to go to art school. I could have gone in any of those ways. I would have been happier I think – and people don’t believe me – as a painter-type artist than in a rock band, but that wasn’t my journey.

You also reveal that when you auditioned for The Detours (the group that became The Who) in Roger Daltrey’s bedroom, one of Roger’s criminal acquaintances was hiding under the bed.

Yes, Roger only told me that a couple of years ago. There were two brothers [names withheld to protect the innocent – or guilty] that we knew. XXXXXXX was totally crooked, a villain, but always really good to me. I used to see him at Acton baths a lot, and he had the most beautiful girlfriend. The other one, XXXXXX was awful, an awful man. They would have been a year or so older than us, which makes a big difference. Roger knew them both and liked XXXXXXX. But XXXXXX had got into trouble and rushed round to Roger’s place and was staying under his bed. So he’s there while Roger’s going, “Can you do [The Shadows hit] Apache?” I was sat there doing my [Shadows rhythm guitarist] Bruce Welch bit and playing the rhythm. Then he says, ‘Can you play [Buddy Holly’s] Peggy Sue? And then can you do the Shadows steps?’ So I practiced the footwork. Then he said, “OK, see you Tuesday.” But that audition came almost six months after he had walked up to me at school in my GCE period and said, “Do you wanna join my band?” I was like ‘Yeah’. But I didn’t get the call until much later. So I was sat there drumming my fingers waiting. And I didn’t get the call to audition until I was at art school

You also write about only discovering that John Entwisle was a freemason when you went to his funeral.

It was because he was so disparaging about his stepfather who was a mason. He hated his stepfather until he grew up and then he loved him. John’s stepfather was a good guy. John’s dad was a Welshman who we all liked, as he used to come to gigs and he was in a big proper mining choir. John brought that choir to our studio a few times, and got them all pissed and he would produce. But, John was a mason, yeah. We knew that John’s first job was at the Acton Inland Revenue and we used to think at that time the masons had infiltrated the Revenue. Nowadays they’re less mysterious, more like the rotary club.

The differences between yours and Roger’s teenage years are very apparent, though. He’s an apprentice steelworker; you’re basically a lazy art student…

Yes, I had it a lot easier. It was a very liberal time at art college – even more than at university. You were supposed to start at ten, but if you showed up at eleven, the lecturer would just so, ‘Oh, Ok you’re here.’ Nobody gave a fuck. My son [Joseph] is now at St Martin’s and part of what they do is train you to have the initiative to work on your own. At the time, I just thought it was just a case of, Great, I don’t have to get up.

In the past when Roger has talked about getting me out of bed to go to a gig, it was a rare occasion when we had a gig in somewhere like Blackpool, and we had to leave at seven o’clock in the morning because he’d bought a truck that would only go at 45mph. So it would take us all day. But there were days when he arrived at our flat [in Ealing] and me and Barney would have spent the day with a couple of gorgeous girls. There were some fantastic looking girls at the art college, one of whom I was lucky enough to marry. Beautiful smart women, and we’d be sat there smoking grass and listening to Jimmy Reed, and at half six, you’d hear this knock on the door. And I’d think, “Oh shit! Now I’ve got to play at the Peckham whatever it is…” And in walks Roger. “Alright then, come on!’ I would be like, “Urrrgh.” “Come on, get your gear, you got your suit?” And of course I didn’t want to get the crimson suit I wore for gigs out in front of the girls. And I’d always look back as I was leaving, and Barney would say, “Don’t worry Pete, I’ll look after them.” Fucking awful. Roger did get me out there, though, and I think if he hadn’t I would have stayed there. I know people my age from school still sat there smoking grass and frozen in time.

That was the trouble with my age group. We smoked a joint and thought, Ah that makes me feel nice. Then you put a record on and it was like, Aaaaahhh! Remember we had shitty little mono record players, but on dope you were hearing everything in stereo. When I first heard stereo, I thought, ‘Well, this is how it has always sounded to me.’

You also talk about being a late starter when it came sex.

I had mixed stuff about sex. Which was strange. If I hadn’t have gone to art school maybe I wouldn’t be looking back at in this way. I was quite happier to have been smaller than everyone else, younger than everyone else. They’re all sixteen. I am sixteen but I look like I’m fourteen and I am behaving like I’m fourteen. I’m a little boy, happy with that because they, the gang, like me. They hear me playing guitar and banjo and they are like, “Hey!” I can make them laugh, so as far as the gang goes, I’m alright.

But when it came to sex, I remember when I was at Acton County, me and my mate Phil would go to Hyde Park on a Saturday afternoon. It’s nice and sunny. He pulls a couple of girls, rolls over and starts snogging the really good-looking one. The other one’s left, and she’s looking over at me. While snogging his one, he’s waving his hand and saying, “Move in, move in.” But she’s looking at me with a look as if to say, “You move in on me I will fucking kill you.” And on the way back on the train I am saying to him, “Phil, for fuck’s sake, we were in the middle of Hyde Park with everybody around and you’re trying to fuck this girl, while we’re surrounded by… spaniels. Explain it to me.” And he goes, “Oh OK, you’ll understand one day.” And he was the same age as me, and he was always very kind to me, and we were mates, but he got it – and I didn’t.

Then what happened was suddenly at art school and in the first year, there were two girls that I can only describe as quantum nymphomaniacs. They shagged everybody. And there were occasions I would go round to my mate Tom Wright’s flat, and listen to some records with one of them, and he’d say, “Can you see ‘Sue’ home?” And I’d say, “Oh yeah yeah.” We’d be walking along the road and she’d say, “I only went to see Tom so I could have a fuck.” I’d go, “Oh really, you must be very disappointed.”’ And she’d say, “Yes, because I really wanted to have… a fuck.” “Oh, Ok, yes, you’re home here now. In you go.” The next day Tom would come up to me and say, “She fucking spelt it out for you Pete.”

And then you lost your virginity, and, according to Who I Am, while doing so accidentally stood in a bucket of wallpaper paste…

[Laughing] Yes. Yes. But when it happened it happened, and from then on I was equipped. It happened when it was meant to happen – when I was eighteen. Very late for some but fine for me.

You mentioned that a lot of people at art school thought you were gay, and that you were slightly disappointed that Kit Lambert didn’t fancy you.

I was quite happy with that, being thought of as gay. I was disappointed Kit didn’t fancy me, but only because I wanted his absolute approval. Kit didn’t like pretty boys, if I was a pretty boy in any sense of the word. He liked street urchins, so the boys he brought home shared a flat with him, in the morning over the scrambled eggs, I would try to chat with them to make them feel at ease. But they were rent boys really.

Kit was your mentor, but he also seems to have had a profound effect on Keith Moon as well…

He tried to. The posh stuff Keith got from Kit – finding out which champagne he should order, which was the best. So you’d be in a nightclub with Keith and he’d suddenly start shouting for “Dom Perignon, 1926!” He got that from Kit. Kit encouraged him, Apparently Keith would rock up to the Track Records office on Old Compton Street and say, “Give me £5000 and put it down to Townshend”, and they would do it. So a couple of weeks later, I’d see this thing that said, “£5000 – Pete.” And I’d say, “What the fuck’s this?”

Do you think Kit and Chris Stamp’s nurturing of you sometimes alienated Roger and John.

Kit nurtured me as a songwriter and thinker. That’s what he did. Chris gave some edge to that by coaching me to be strong and deliver my ideas powerfully and confidently. What they both did, coming from a film background [Lambert and Stamp had been director’s assistants] was to accentuate the importance of the creative team – that you have to be part of a team but there can only be one director. But that this role also shifts, sometimes it’s one person, sometimes it’s another. However, the way they coached Roger was by pushing him out. I don’t think they did it that consciously, but it was hard to watch. John was regarded as the most conventionally good looking in the band, so he was just encouraged to stand there and be cool.

At the same time, modern bands and their managers could learn what not to do from what happened with Kit and Chris in The Who.

When I started this fucking book, it could have been used as a manual. But in the last five or six years everything has changed so radically in the rock business and record industry. It is pointless. You couldn’t read my book and learn anything. All bets are off. But it was like the Wild West in the sixties and seventies. It was a frontier.

Is it true that Malcolm McLaren went to see Chris Stamp for advice on managing the Sex Pistols?

There’s a story that Chris told me. He was there the evening I met the Pistols for the first time. We were walking back from the Speakeasy where I had got into a few fights, and Chris said, “Do you want to know my part in the Sex Pistols story?” And he told me: “There was this guy Malcolm McLaren and he used to show up at Track Records and said, Can I talk to somebody? I said, I’m Chris Stamp. He said, Are you one of the Who’s managers? I wanna form a band that will be bigger than The Beatles.”’ Apparently Chris said, “OK, I reckon The Who could have done it, but they haven’t done it.” Malcolm said, “No they haven’t done it, but, yes, they coulda done it. I am not here to tell you what you did wrong. What I want to know is how you found them. What you did that made The Who.” So Chris said, “Well, we went out to this club and found the four ugliest guys we could find – they were idiots, they were cunts and they couldn’t play – and then we added our panache and gave them a decent name, dressed them up nicely, and that was it.” And Chris says that when he heard that McLaren went “‘Gotcha!” And that’s kind of what he did. That’s not necessarily the way that Steve [Jones] in the Pistols or John Lydon sees it but I don’t think they would argue with it. Chris Thomas who produced Never Mind The Bollocks and my solo albums said Malcolm said [of the Sex Pistols], “I want this to be bigger than the Beatles.” That was his pitch.

The reader gets a real sense in the book if you feeling a bit adrift in the early 1980s, but also how much you liked a lot of the new music around at this time.

I liked it. I liked the fashion thing as well. I was open to the synergy. I remember going to New York and seeing Adam And The Ants live – and they had two drummers! It was sad to see Adam struggling to get past what he did then. It was so exciting and so colourful and his make-up was extraordinary, and everyone in the audience was dressed as pirates. Stuff with Duran and Echo And The Bunnymen – there were some good music in there, occasionally extraordinary stuff like Teardrop Explodes, who were mind-blowing. But, yes, The Who were struggling at that time. I am at a critical point personally, because I was past thirty but I was still trying to dress the part – and getting away it just about [laughing].

But at the same time you were a musical hero to new songwriters such as Paul Weller.

The trouble with Weller was, because he was a huge fan of mine and had great respect for me, he would sit in a club somewhere with me and say, “Don’t look back, Pete, don’t look back.” And I would think, Actually, the whole mod thing was about looking back. But I also felt that I had a duty as a writer to serve our audience who were also ageing with us and experiencing the same difficulties.

Was that the thinking behind The Who By Numbers?

When we did The Who By Numbers, it was just pre-punk, the songs are about being older, feeling lost, losing your way, about changing fashions, being sentimental and looking at the sunrise. What’s that got to do with being a young man? You don’t start looking at the sunrise until you’re dying. But Roger picked those songs from my demos.

Roger’s an actor. I don’t think Roger Daltrey realised that – and I certainly didn’t until he started doing Tommy the movie. I don’t think he realised that what he was doing all the time with my work was interpreting, acting – and I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t be an actor and he could. And he has become incredibly good at it – at being the mouthpiece. Now he could take any of my songs and sing them. I hear that on his solo tour he’s been closing with that ukulele song, Blue Red And Gray [from The Who By Numbers], a very soft, sentimental song about family life and me living at the bottom of the hill and Ronnie Wood living at the top of the hill in the house that I now live in.

Talking of Ronnie Wood, critics are already having a field day with your description of Mick Jagger’s “long, plump penis” and how he’s the only man “I’ve ever seriously wanted to fuck”. Any word from Mick himself?

It’s just fun. We are good friends. Mick hasn’t come back to me, and he wouldn’t bother. We talk about much more serious things than that. I very much doubt that he had a five-second anxiety about what Keith [Richards] said about his dick either [in Richard’s autobiography, Life] – a man who has shagged some of the most beautiful women in the world isn’t going to worry about that. ‘Oh, wasn’t I big enough, dear?” I better ask the next 10,000 women.’

You also describe a couple of bi-sexual experiences.

I just thought it was the truth. So I might as well put it out there. But the trouble is when you tell these stories, people go ‘Oh, it’s just the thin edge of the wedge, where there’s smoke there’s fire…’ A lot of my mod friends from the Goldhawk [club, Shepherd’s Bush], younger than me, tried being gay, and they tried it out because it was fashionable and trendy thing to do. But also because in that little circle, we thought Rod Stewart was gay because he performed with Long John Baldry who was openly gay; we thought Marc Bolan was gay because Marc had said ‘I was a rent boy at The Scene club [in Soho], which was a radical thing to say.’ We thought David Bowie was gay because he hung out with Amanda Lear who was a transsexual. We thought all the cool people were gay. But, most importantly, because Kit Lambert was gay we thought Chris Stamp was gay and he was fucking gorgeous, handsome better looking than Terence, and a mod.

In Who I Am you talk about sometimes feeling “a few steps behind” some of your contemporaries. You’re unusual among rock musicians in that you admit that.

It might surprise people. But the only guy I know that doesn’t have any shade of self-doubt is Sting, and is therefore very difficult for us to deal with because of that. We all find him difficult – because he is so immensely talented and writes this beautiful stuff. But there is something about this man who is so self-assured he can leave The Police…. Others – Paul Simon, Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Ray Davies – and these are people I know pretty well, some better than others – they would have no difficulty with agreeing when I said there were times when I felt out of step, and very lost. They might not admit that in public, but I can, because I have nothing to lose. The truth will set you free.

But those days when I felt out of step and threatened by various other vogues – what happened every time was I would come out of that phase and do another Who gig, and it was exactly the same. We were still popular. Nothing had changed!

In a way I realised that what’s actually happening is the Who gig is like the Saturday football match. I’m on the pitch kicking the ball around, doing fine, but afterwards I am going to nightclubs and there are people there who look a bit cooler than me. What you want to do if you really want to bring yourself down is you pick the most fashionable nightclub in town, and go there and try to fit in. And I did that all the time to myself. And I still don’t know why. I never liked pubs. I didn’t like nightclubs. I had to stop because of the drugs and alcohol. A couple of my mates, ex-footballers, who run nightclubs tell me that they just have to walk around all night and pretend.

Discussing your arrest, you reiterate that the reason you used your credit card to access child pornography in 1999 was not for sexual gratification but “to run a story on my website illustrating that online banks, browser companies, and big-time pornographers were all complicit in taking money for indecent imagery of children.”

I deliberately chose a website that I thought was a ‘sting’, where child porn was being advertised but not necessarily delivered. When I was filmed at the police station [for the BBC documentary Police Protecting Children], I was in shock and making it up as I went along. At one point [the police] said to me, “Describe what you saw [on the site]”. I said, “I suppose, children in a state of undress… I dunno.” I didn’t see anything. But it was mea culpa because I admitted on the day the story came out in the Daily Mail [claiming that a rock star was on the list of names sent to the child porn investigation team Operation Ore] to having used my credit card. What I wish I had done is written about this in my essay A Different Bomb [about internet child pornography] which I’d published on my website in 2002. I should have explained it then. Now it turns out that [the investigative journalist] Duncan Campbell examined the hard drive of the website I visited, but couldn’t even find my details. He wrote about it in a computer magazine [PC Pro]. That was a revelation. It was amazing to hear that.

Do you think the police thought you were a paedophile?

I got a letter this weekend from a guy at Twickenham police station who was the head of the campaign. He wrote to say “at no point did we think you were guilty… and that the press hysteria actually undermined our operation to the extent that we lost track of people who we believe were active predators that we could have stopped”. But he mainly wrote to reassure me: we believe you and we still do. But he did also say, “but not everybody does”.

How do you feel about the doubters?

People will always look at me and say, “paedophile”, “innocent”, “guilty”, “must be a paedophile ‘cos he’s got a big nose”. But I know the word ‘paedophile’ will be in there somewhere. I can’t change the past. I describe what I suffer from as ‘White Knight Syndrome’ – this idea that I can help, but in an area that is irredeemably fucked up. Also NPSCC had this campaign called Stop It Now which was addressed at men using the internet for porn. Yes, easy enough to say [laughing]. But I think what they were trying to do was alert men to the possibility that you weren’t going to get what you thought you were going to get, and you could end up breaking the law and hurting children if you go on doing what you’re doing. But in the end I didn’t go there with that campaign. I still support Rescue which is a women’s aid charity, and another which helps the children of domestic violence have holidays and so on. But my main thrust is with NAPAC. It’s a helpline with adults that might have suffered. You wont get me on the phone but you will get someone that will listen and help. It’s about removing the stigma. I still support NAPAC [National Association for People Abused in Childhood]. They have a helpline, and I still believe that what I’m doing comes from a good place. It’s all about trying to remove the stigma of abuse. I would have liked to have written more about this in the book. But there are a few bumps in the book, because of the editing. I would have liked to have included this guy’s letter in the book.

What’s next?

We are touring Quadrophenia, and Roger and I agreed to diverge a bit. He wanted more control of his band, and he wanted to do Who music, but do it his way. He enjoyed touring with his band, but what he enjoyed most was being able to control the sound and being the only one on the stage that the audience looked at, and not be distracted by me up there as well making comments. He had an affirmation, I think, close to an epiphany. Roger has changed. He is a different man. So much happier. So much more fulfilled. So much more confident. So much more a musician. It’s been a wonder to watch. I persuaded him to do the Superbowl. He said, “Nah, I don’t wanna do the Superbowl.” I said, “Come on, there’ll be eight million people”, so I persuaded him to do the Superbowl. And at the Superbowl I said to him, “Listen, this is my master plan – let’s do Quadrophenia at the Royal Albert Hall the following March, and we can tour it, if you like it and I like it.” And he said, “What d’ya wanna do that for?” I said, “It would be good for my ears. It’s quiet. It’s a piece.” And he said, “I will do it if you give me complete creative control.’ And I said, yes. And so we did it [in March 2010], and people rushed back after and said “Amazing! Social document! Quadrophenia…!’ and rushed back to Roger and said, “Wasn’t it amazing!” And he said, “Nah, didn’t like it.” But you had complete creative control Roger [sounding exasperated]!

The mistake we made is that [the Royal Albert Hall show] was in the week that Roger organises these ten days of concerts for Teenage Cancer Trust, and he’s all over the fucking place trying to get Florence And The Machine and the Stereophonics, and talking to kids in clinics and meeting the health secretary. He didn’t control it. He just did it. He said the problem was he couldn’t find himself in [the piece] anymore. There was a key moment where we decided that the godfather was going to be Eddie Vedder, the Who’s best friend. So Eddie comes over, an adorable guy, and he’s the godfather to Roger’s ‘Jimmy’. Of course, it should have been the other way round. But Roger found it impossible to process.

A couple of years pass, I write this fucking book, and this summer I persuaded Roger to do the Olympics in the same way I persuaded him to do the Superbowl. At one point neither of us wanted to do it – “Oh there’ll be a traffic jam!” – but slowly and surely we both started to get the intuition that it was going to be alright. And he said, “Can I have complete artistic control?” I said, “Yeah, as long as it doesn’t turn out like Quadrophenia.” And we did it and I think what we did was great. So immediately after, we start talking about can we nail down a Quadrophenia tour and he said, “Yes, if you give me complete creative control.” We are about to rehearse at the end of October. I have no idea what he is going to do. But I sense that even if what we do doesn’t work out brilliantly well, what’s wonderful is in a sense Roger has started a new life. We shall see.

What have you learned about yourself from writing the book?

What I am looking for with this book and with the next stage in my life is true creative freedom.

Could that lead to another Who album?

I don’t feel that I would have any problem rising to the challenge of doing something for The Who brand. Endless Wire helped me do that because what I did was writing a couple of what I thought were typical Who songs and the rest were just songs.

This summer and last year and the year before, I’ve been working on songs for this dramatic son et lumière scenario, Floss. It’s a very very ambitious project but I have been thinking it might be something I could do on the Internet – or maybe not. But I was very encouraged to see Roger Waters taking out The Wall. In a sense it’s like a big Cirque du Soleil meets The Wall in the open air, starting in the afternoon and carrying on until the stage is in complete darkness, because the final scene is a rock star on a stage.

Would it be a Who piece?

It could come out under the Who brand. I have written it in two parts. Roger could narrate the first part. But I did fly The Boy Who Heard Music book past Roger before we talked about it. And after a couple of weeks, I said, ‘You haven’t responded to my book – what do you think? He said ‘I flicked through it.’ I said, ‘Will you read it?’ This was in 2005. He said ‘I’ll read it tonight.’ So I called the next day and said, ‘Have you read it?’ He said, ‘Yup, but Pete it’s the same old shit isn’t it…’ [The Who’s PR gestures that our time is up] And on that note…

© Mark Blake, 2012

www.markrblake.com