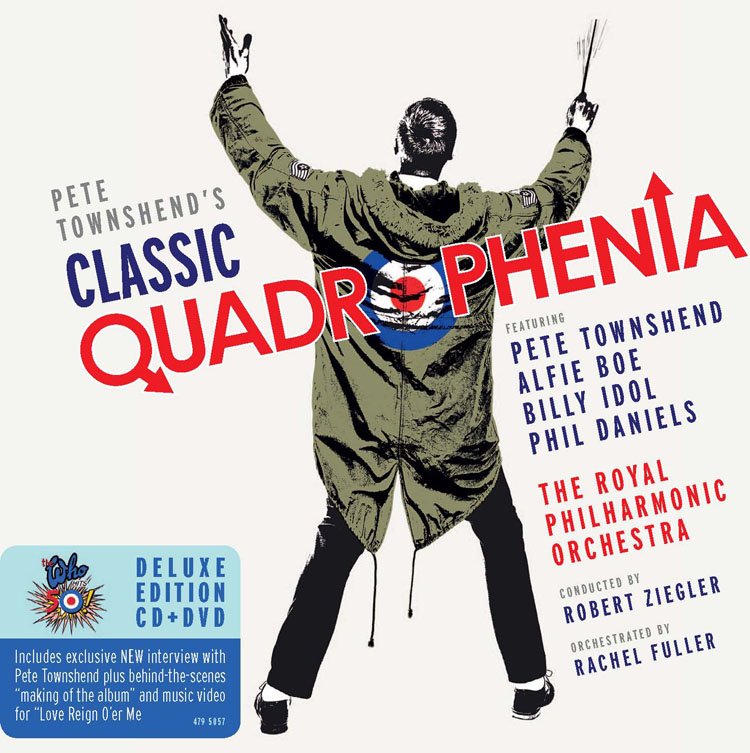

Pete Townshend released Classic Quadrophenia on Deutsche Grammaphon this week. The deluxe edition includes the complete CD and a 44 minute DVD featuring an exclusive on-camera interview with Pete Townshend and Rachel Fuller, a behind-the-scenes look at the making of the album, and the new music video for the song Love Reign O’er Me shot on-location at the infamous Brighton Beach Pier in England, site of the Mods and Rockers riots of 1964.

Recorded with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in October 2014 at London’s legendary Air Studios, conducted by Robert Ziegler, and featuring popular Decca-signed British tenor Alfie Boe on vocals, with Townshend himself on electric guitar and performing cameo vocal roles along with special guest vocals from Billy Idol and Phil Daniels.

Pete will reprise his roles at the live world premiere at the Royal Albert Hall in London on the 5th of July 2015, alongside the RPO, Ziegler, Boe and other star guests.

The new symphonised version of Quadrophenia, an album originally released by The Who in 1973, was orchestrated by Rachel Fuller, a professional composer, orchestrator and singer-songwriter in her own right and also the partner of Pete Townshend.

This project is the latest chapter in Pete Townshend’s lifelong mission to break the three-minute mold of the traditional pop song and take rock music to a higher artistic level. In the 1960s he defined the concept of the rock opera with Tommy, taking it a stage further with Quadrophenia.

Pete began work on the project as part of his plan to leave a legacy of all his work arranged for orchestra as sheet music, for future generations to enjoy. Pete hopes the new work will go on to become a regular part of the orchestral repertoire and boost attendance at classical concerts.

Alfie Boe, who sings the parts originally sung by Roger Daltrey, was also born in 1973 but has been listening to Quadrophenia for years. “Its in my blood. I grew up on rock music and always had that fantasy of being a rock singer before I trained as an opera singer. Ive always thought the classical voice can lend itself to this type of repertoire. Its harder than opera, but thrilling to sing. The music is so full of excitement, positivity and strength I wouldnt separate it from a symphony by Beethoven or Mozart” - Alfie Boe.

Alfie Boe Jimmy (vocals on tracks 2, 4-15, 17)

Pete Townshend Godfather (vocals on track 5, guitar on tracks 6, 13)

Billy Idol Ace Face/Bell Boy (vocals on tracks 4, 10, 12, 14)

Phil Daniels Dad (vocals on tracks 7, 8)

Order the Classic Quadrophenia Deluxe Edition today!

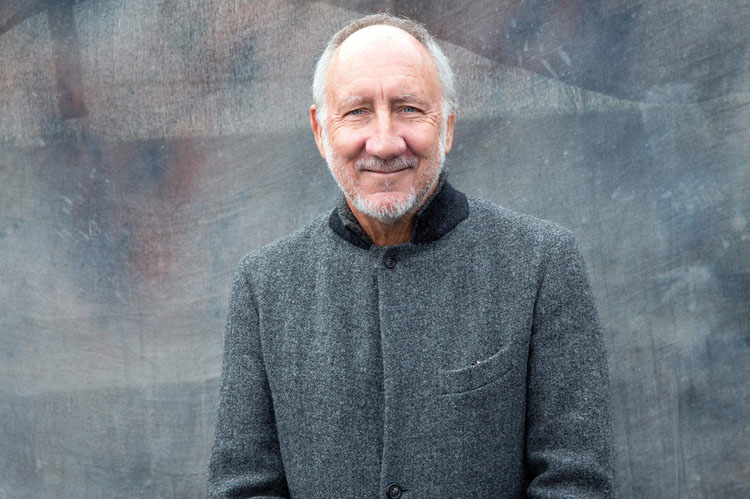

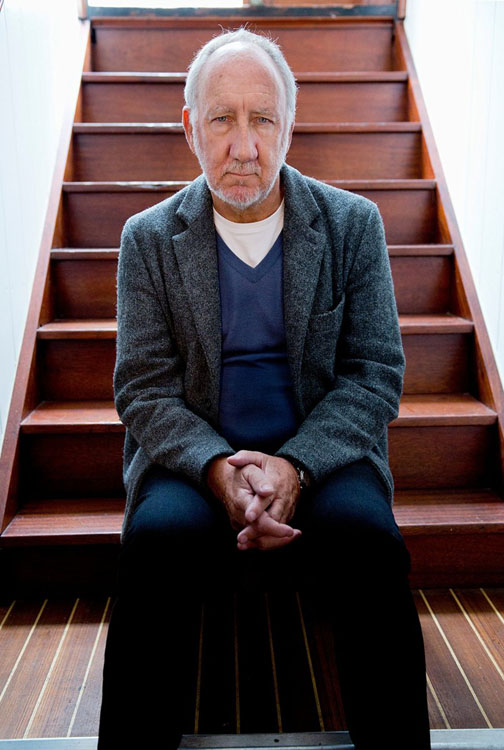

Photo © Jill Furmanovsky

Pete was interviewed by Tim Cooper, and video clips are included in the deluxe edition. An extended audio version will be included as a bonus track for the album up on Spotify. Here is the complete transcript of that interview.

Interview by Tim Cooper

So I guess the initial question is: Why turn a classic rock album into a classical rock album?

I wouldn’t call it a classical rock album, I think it’s just you know taking a rock opera or an oratorio or whatever you wanna call it and just moving it into a different genre and I think it deserves it. You know I always felt that Quadrophenia is one of the best and most cohesive theme based and thematic, you know it has themes that run all the way through, probably superior to Tommy in that respect, so I think it is totally appropriate to do it, but it is not something I set out to do. I just wanted a folio of an orchestral version so that when I die an orchestra somewhere might one day perform it. Rachel who did the orchestration – my partner Rachel – was creating demos and it was quite clear that this music you know was taking a life of its own.

Why is it important to you to make an orchestral version and does doing so suggest that someone who made their name as a rebellious rock’n’roll figure has finally become a part of the establishment?

I fully expected that kind of question from you [Tim laughs], in fact you asked me it before I think. In what way does doing an orchestral version of Quadrophenia make me part of the establishment? You know I’ll throw the question back at you. I think your thinking is archaic, insulting, extraordinarily kind of just dumb. I think that music always suffered from being tied to any kind of political or even social or even spiritual or religious connection and as a musician I have always really wriggled [?] with that. So, you know, brought up with my dad, who was in a swing band in the war, and my wife’s father Ted Astley was orchestral composer who did film scores, and both of them always said to me: ‘snobbery in music, whether it is up or down, is bad.’

The weird thing about being in The Who, which is the…, yeah I suppose we were rebellious, and I suppose we were for a while or seemed to be anti-establishment, but that wasn’t us really. I think we were truly reflecting what was going on around us, you know the schism that is at the heart of the Who is not the schism that is at the heart of the difficulties that Jimmy, who’s the hero of Quadrophenia, is going through. The Who were a post-war band who were part of that post war group of people who included the mods who seemed to have no function, and it wasn’t true in America, I don’t think it was true for some of the other countries in post-war Europe, but it was very profound in the UK and nobody has ever been able to properly explain why. You know we felt that we had no, we could never be as good as our fathers and our grandfathers who had fought in these magnificent and absurd wars and had both validation and valediction and that what we actually had was to prove ourselves at street level, and I happened to be in a band doing that.

I suppose I could have ended up playing the clarinet like my father and if I had I probably would have ended up playing in an orchestra, I don’t know, but as you know I went to an art school, so my journey was slightly different, but I remember watching - I was an observer – as a composer, as an artist, as a fashionista, I was watching my audience very very carefully observing them and trying to have a function for myself, but also in a way trying to create as an artist a way that they could speak through us. And in the early days of The Who, maybe the first four five records, I think I achieved that very well and so did the band. I think “My Generation” is the best example.

Quadrophenia became necessary later on to remind us that that was what we were supposed to be doing, not Keith Moon dressing up as Adolf Hitler and getting on the front page of the Daily Mirror, but Keith Moon playing the drums in such a way that the people in the audience felt elevated and lifted and freed from the drudgery of their day, but also filled with a sense of possibility. Being a young man in the sixties and the early seventies, just pre-punk Quadrophenia was as well, the possibilities were good and there was the cause for optimism mainly to reconnect The Who with their audience.

I must tell you that this question was sent over by your American label. It was not my question.

Well, there you go. You did ask it. [laughs]

When did you decide to do this orchestrated version and how did you set about making that?

Well interestingly enough, hopefully you’ll meet her later on, Rachel who came into my life, Rachel Fuller who did the orchestration, came into my life, I had decided like twenty years ago that one of the things I wanted to do was to make folios of all of the story based collections that I’ve done and it started with one which is called A Quick One, While He’s Away which is on The Who’s second album, so that was 1966. I did another one in 1967 called Rael, I then did Tommy, I then did one called Life House which was a failed concept album, I then did Quadrophenia, and as a solo artist I did White City, Ironman, Psychoderelict, and then for The Who last time another mini opera short form collection of songs called Wire and Glass. I wanted to see each of these pieces in a book for orchestra and that was what I wanted. And I started on that and met Rachel at a rehearsal room in London and it turned out she was an orchestrator and she was pretty, but she was an orchestrator. So I managed to track her down and asked her to do some work for me, and the first thing she worked on was Lifehouse Chronicles which was performed with a small chamber orchestra and a band at Sadler’s Wells. So I started just really wanting these books, you know I imagined myself as an old man: I’m in my country mansion, you know I’ve got a couple of dogs, and I go into my study and I’ve got this A Quick One, While He’s Away that was a good one, and then Rael that was a good one, and then right the way through and somebody would ask me the daft question: ‘why would you bother to do this.’ And I would say: ‘Because I think this is fabulous work and one day perhaps an orchestra like, you know, the London Philharmonic will perform it.’ So that’s how it came about. That’s really something that I wanted and I started to want it quite early in my career.

It’s weird though, but when we were working on Tommy, Kit Lambert who was the producer was the son of Constant Lambert who was, he was one of the people who started Royal Festival Ballet and the Covent Garden Opera House, he was the Director there for a long time. Kit Lambert really wanted Tommy to be a proper opera. If you listen to the recording, there is hardly any electric guitar on it, and that was because he always wanted to add an orchestra to it. And I fought, I really fought against that. Subsequently a classical or orchestral version of it was done by a guy called Lou Reizner, and I remember sitting and listening to it and thinking, this isn’t perfect, it is not precise to the music that I have written, which I think Rachel’s version of Quadrophenia is, but it made me realize that music is music. And actual fact what a rock band was, as my father once said, with a couple of guitars and amplifiers you are replacing an old fourteen piece band. You can make more noise, you’ve got less people in the band and of course the distortion was what created the harmonics the distortion of rock music was what created the richness of the sound, a couple of guys with a couple of distorted guitars are equal to a huge church organ.

Speaking of that, can you describe the contrast between recording this album in three days in a studio with x number of musicians and choirs, and however many days it took and however many musicians were involved back in 1973?

Well recording The Who’s album brought up a lot of other problems. There were technical issues. I wanted a quadrophonic album so we had to build a quadrophonic studio, there wasn’t one in London at the time, so we built one. That took about three months. I think the guy that built it for us used an out of work circus, a troop of circus workers to build it. The session went quite quickly. I’d spent a long time working on the music before, so I had demos, I had recorded demos and I had a studio in the country which had a quadrophonic mixing system. So I took the band there and started to work with them. I had synthesizer backing tracks which I already developed for some other pseudo orchestral elements, violins and horns and oboe and John Entwistle could could play almost any brass instrument with valves and he put on trumpets baroque trumpets, tubas, sousaphones all kinds of things to complement what I’d done. At the time we finished we did have elements where we had a massive pseudo orchestral sound anyway, in places. The album was mixed fairly quickly and we went to my studio in the country and a guy called Ron Nevison went on to become a quite big record producer in the USA with Jefferson Airplane, Heart and various sort of other Heavy-Rock bands. He and I just together went into a room, mixed it, took it to rehearsal.

The band never ever managed to play it live very well because we were so rushed in the release but that process went from August of ’72 on and off, we were touring during that period mainly in the UK, some shows in America and Europe, and we finished, I think, in about December, something like that, and the album came out at Christmas. So it was a relatively long process but it also felt very intensive and it was great fun, It really was fun. It was one of the nicest times for me, working with The Who. It was the only record apart from Substitute that I produced. So I was able to get exactly what I wanted. I think Roger did an amazing vocal performance, and he and I were at terrible odds through the recording. We weren't on very well but his performance is what is fabulous none the less. The band were playing very well, Keith Moon, I wouldn’t say he was at the height of his powers but he had not yet gone into physical decline which he has soon after. He was thick and strong and funny and wicked.

Compared to the classical version, the orchestral version, which was, you know I asked Rachel to start working on it like two years ago, but probably two and a half years ago. I waited. The music came out in drips and drabs and finally it was done and she produced a score, she got an assistant, she started to produce demos. Next thing I know we did a test at Air studios, it sounded fantastic, the test was luckily with the Royal Philharmonic, they agreed to do it. We hired the Royal Philharmonic, they loved what they did and they said, they would like to become associated with it and then we did that session, and as you say, you were there, it was three days of work.

Compared to the classical version, the orchestral version, which was, you know I asked Rachel to start working on it like two years ago, but probably two and a half years ago. I waited. The music came out in drips and drabs and finally it was done and she produced a score, she got an assistant, she started to produce demos. Next thing I know we did a test at Air studios, it sounded fantastic, the test was luckily with the Royal Philharmonic, they agreed to do it. We hired the Royal Philharmonic, they loved what they did and they said, they would like to become associated with it and then we did that session, and as you say, you were there, it was three days of work.

What was amazing about Royal Philharmonic, a particular surprise to me I’d always found that classical performers didn’t get the inferred syncopated rhythmic nature of Rock and Roll. They just didn’t get it, or R’n’B or pop music. You know they couldn’t get that … [Pete performs rhythm] knocking a beat out of the window. These guys do! It’s partly I think because they had been asked to perform an extraordinary work for composers in film particularly blockbuster Hollywood movies. But also because they are young [laughs], they’ve grown up with this music. So they understand it. And what was amazing was going in and putting these sheets of music in front of these guys and they start to play and it is… they were like a band. They were like a well-rehearsed band. We did five songs and we could have taken the first takes. We really could have taken the first takes. They are so excellent.

So we had a good conductor with Robert Ziegler, the scores speak for themselves. What was interesting was their sense of rhythmic sensibilities. There were bits when I had a little tear in my eye when I heard how beautiful a song like Love Reign O’er Me sounds with full orchestra, but the main thing was that I was sitting there thinking ‘This fucking rocks!’ It rocks, you know it is different, you know there is no drummer there’s no one going [Pete makes drum sounds] there is no loop going round going [makes a beat with beatboxing], it is just an orchestra and somewhere in there there is a heart beat, there is no click, film scores, they’re going to click, you know a ‘tick, tick, tick’ which may speed up or slow down. The conductor hears it. Some of the principles in the orchestra hear it. This was just: ‘Play this guys, play it without a drummer, play it at your own speed.’ And back it came. It was a revelation.

Your own personal musical involvement is limited to playing guitar on two tracks and sing…

Which I really didn’t need to do, play the guitar but I... you know…

And you’re singing on three or four, I think.

Pete: No, I am singing. I play the role of the godfather. Which is entirely appropriate, I think… [laughs]

Did you have to rein yourself in? Just to stopping yourself contributing more and more and more?

Pete: No, no- I didn’t want to be involved at all. I saw myself doing a Beethoven, deaf listening to my ninth symphony and not hearing a bloody note in a box with coca cola and some nuts. Unfortunately I will have to be back stage and have to go on. I won’t hear it, so that’s a pity [laughs].

How did you choose the collaborators and you might perhaps tell us who they are?

The first choice was obviously very very critical which is who is gonna orchestrate and Rachel was of course right under my nose but as I said earlier, I always had an intuitive feeling and as I’ver got to know her better I had an absolute conviction that she would be able to do a wonderful job on this kind of work. And I thought that actually Quadrophenia might be the hardest challenge for Rachel. Rachel then through Hans Zimmer... I asked Hans Zimmer the film composer who I knew, he’s an old friend to help Rachel to put together a studio for making demos. He let her use his Soho-studio and a couple of his assistants and through them she found her assistant Martin Bachelor who did a lot of the percussion writing, ‘cause he is a drummer but he is also in a choir so he helped us fix the choir.

Paul Curran, a guy who has been working for me for about three or four years, he is the creative manager of the whole project. I brought Paul in to do everything in my career and in my life that is not The Who. But not necessarily only looking forward. He is involved with me in all my creative projects and everything new that I wanna do, but he is also after all the stuff that looks backwards as well. We then decided to do these recordings and luckily I had an interview with a guy, with Robert Ziegler, he interviewed me and I told him about this project and how it was then unfolding. He turned out to be not only a radio journalist in the music field but also a conductor for the BBC Concert Orchestra, and he arranged for Rachel and I to get involved in a performance of two of the pieces which were ready to perform in a concert at Queen Elizabeth Hall.

Jeff Beck came along and we both played guitar. Instead of having voices, we played guitar. So that was the first step to kind of realizing the whole thing. For a while it looked like it could be a thing that we would do with the BBC Orchestra but then we decided to do a couple of demos because it was clear that this piece did have a life. So we did these demos at Air Studios, Rachel suggested that she wanted the RPO and we managed to get them on a day off. Simon Rhodes is the engineer at Air. It all just came together, as I said earlier. They are the principles.

Pete with Rachel Fuller, Alfie Boe, Phil Daniels. Photo © Jill Furmanovsky

And what about the singers?

The singers… we had it finished pretty much, we knew where we were going with it. Rachel and I were both confused in the sense as to where this might go. I have to say that I don’t think either of us ever imagined that we would use regular operatic voices. Although at one point we thought about Il Divo; you know there are four of them and there are four facets of Jimmy. But that was more about being four of them than the fact that they were operatic tenors. We had a meeting with Deutsche Grammophon and Mark Wilkinson, who is the president of the company, [and he] suggested Alfie Boe.

By chance my daughter's first boyfriend James Morgan is an organ scholar, was doing some other work or me on another project and he’d done some work with Alfie Boe. I happened to be meeting him a couple of days later and he said “Alfie is really great!”. Rachel did some research and we did a test with him and he was just wonderful. That was the “it”. It was done.

I was doing the godfather, we only needed two other roles. One was the Ace-face who becomes the Bell Boy so it is a dark role that turns into a comedy role and the other was the role of the father. There was a possibility at one point that we might use a female voice but we decided not to. We did it a little bit here and there; we asked all kinds of people to do it and all kinds of people considered it. We wanted whoever worked on the album to appear at the Albert Hall, so that was a constraint. Billy Idol had done such a good job as Ace Face and Bell Boy when we toured it with The Who in 1997 that I invited him and I was quite surprised when he agreed. He is ten years older than he was then, but he has done a great job, and I mean, natural for the dad was Phil Daniels who plays Jimmy in the Movie, and that’s our cast.

Did you consider asking Roger Daltrey to sing it?

Absolutely not. [laughs]

Has he heard the finished result?

Ehm, no. And I think it was important to me to acknowledge, probably more for Rachel than for me, that this was really something that as much as possible should have a life and a track that would be not away from The Who, it is part of The Who and it is part of The Who’s history, but that would be pure. I will maybe take a little bit more time to explain exactly why we didn’t consider it for a second. The Who, while Rachel was working on the orchestration, did a tour of Quadrophenia. It was the first really seriously properly arranged, both music and the video presentation using modern techniques and Roger agreed to it. It was incredibly good, it was wonderful to work on and the reviews were fantastic. The crowd loved it. I felt that at that time Roger was spent by he was so immersed in it, but in an incredibly abstract way Roger had found a new way of being Jimmy, of singing Jimmy. He’d found a new way of telling the story, he ignored my story that I’d written for the sleeve and taken a new journey which was much more I thought like the journey that I tried to take the listener through in Tommy, the post-war journey. It just felt to me that to go to him and ask him then to sing in front of an orchestra – I am sure he would have done a wonderful job – but also of course the keys are all lower, when The Who do it these days he sings a bit lower. Alfie Boe and Roger Daltrey have had a conversation and according to Roger it went like this: “Oh Alfie Boe, he is a good lad, he is a lovely boy he’s a good lad.” and he said “God this is hard to sing, isn’t it Roger, I don’t know how you have done it”, and I [Roger] said to him “Alfie, you have no idea. Pete writes these bloody songs and they’re so bloody hard to sing…” and that was the singer’s conversation. [laughs] So fuck both of ‘em! [laughs]

Could you content, like a film pitch the story and themes of Quadrophenia, people might be unfamiliar with the work.

Yeah. This is like a journalists story, the newspapers job is to tell us that Lord Jones is dead… who is Lord Jones… [laughs]

For those of you who don’t know what Quadrophenia is about. The story about a young man who is in the mod period, so it’s 1961, ’62, ’63, living in London and he’s having a bit of a breakdown, a nervous breakdown. He’s lost a very good job, he is in love with a girl who doesn’t reciprocate his feelings, he feels he’s a misfit, he doesn’t fit in and it is about how his journey becomes transmogrified, transformed, he’s actually more like into a spiritual quest. I didn’t conclude that what happened at the end of the story but that was the idea of it. That’s the story, he’s a young mod boy Jimmy. The whole story is told from inside his head. He is a fan of The Who, but what’s interesting about that is, in Quadrophenia he disowns The Who [laughs]. In the fifth or sixth song, Punk and the Godfather, he says: “Listen, you've sold out!” I have to fight [from] my corner on stage at the Royal Albert Hall as the Godfather saying: “Listen, I sold out because you bloody well wanted me to!” So, we shall see. [laughs]

Were there any other operas or works of art that inspired you in any way, not specifically but inspired you or that you used as template or inspiration for the project? Or simply that you just love, perhaps contribute?

Photo © Jill Furmanovsky

I have always felt that in Rock music and even Jazz, you know Duke Ellington did some wonderful story based compositions that, they were instrumentals but, he did a couple based on Shakespeare plays. I always felt that I was capable of providing the musical base for an opera particularly, but for a particularly, for an oratorical, a collection of songs that may tell a story or celebrate something. But if you go back to the canon that exists pre the evolution of popular music as we know it, you know, musical, jazz, blues, early jazz, what you see is that music was expressing one thing and one thing only and that was the glory of god. So rock music was actually celebrating the glory of this and that, what’s going on in here, but the struggle for us that we all understand is that we all carry that questions. Is there a god? Do I have a relationship with god, rock was very good at that.

For me, when I started on Tommy, particularly and then subsequently on Lifehouse, which is looking into a dystopian future of advanced and destructive and invasive and dangerous technology, finally Quadrophenia which was really just about a young man having a few bad days, I started to realize that I had an incredibly good foundation and Kit Lambert who introduced me to the work of Purcell and William Walton and his dad had a box at the Royal Opera House, which I could pop into at any time and in so doing I saw a lot of operas that I loved. I saw a few that I didn’t like. I like Boris Godunov now, but I didn’t like it when I first heard it. I wasn’t keen on very much Verdi, I didn’t like very much Mozart, but which I do now, but I didn’t then. I found it very hard to get past.

The sound in the Royal Opera House is pretty crap, it sounds very dry and dead but it was one opera that I saw which I think lies at the very very heart of Quadrophenia and that’s a Benjamin Britten opera called Billy Budd. It really seemed to me… in a sense that was a post First World War story. A Suffolk fisherman takes a boy out to the sea and one day the boy dies and there is the influence also in between Benjamin Britten and his singer Peter Pears. At the time they were lovers I think briefly. I think this was a play and a story about some kind of homosexual or homophobic themes. There was the idea that the village rises up against the fisherman because they feel he’s a pedophile or something.

That was all there and what was so interesting to me when saw it and I am sure it flavored and charged Quadrophenia when I came to write the story on the sleeve … That was ... That’s how mod started, you know it started in this world where young working men were trying to rise, in a sense, up through the establishment, almost through a back door. One big mod venue called the Sane Club was a mod venue where we would hear great music and see new artists, but it was also a pick-up joint for rent boys. Many of whom were the most pretty and most effeminate mod men. And this was going on in Soho before the mods came of course. So there was this combination.

I remember seeing at the Marquee Club once one of The Who closest fans - I won’t say his name, ‘cause he is still around – coming up to me and saying “I went to Paris with Kit Lambert on the weekend”, Kit Lambert was gay, our manager, and I said “ What were you doing in Paris?” and he said “I thought I would see what it’s like to be homosexual” and I said “so, what did you think of it?” and he said “you know, it wasn’t bad. It wasn’t bad at all. It was alright.” And I said “so you’re gonna do this?” “I might, I might, why not, you know. Paris is lovely.” And there was this sense that nothing mattered. But my view at the time, you know is was thinking ‘Oh my god’. One day this is just all gonna be kind of lifted and lights are gonna be shun on it. It’s going to be like Billy Budd, people are gonna be saying ‘What was Lionel Budd doing at all those Who gigs’ Luckily for Lionel now he’s gone. You see what I am saying, there was this link, this sense and some of this is what is the word retrospective, looking back at Quadrophenia and making a link. I happened to listen to Billy Budd about three or four years ago and I thought ‘bloody hell, this is so similar’, you know the boy seems similar.

My final question in this segment I think is, whether you found it difficult to let go of your work when Rachel took over this version of it and what your, I mean, I know you were still involved but at the same time you’re letting her create in parallel with you. Perhaps explain that dynamic, what she’s brought to it and what you’ve relinquished and what you think of the finished result.

I think I was determined not to relinquish one aspect which was what I would call – it is very vague – is the modal harmonic mood. All the words mean the same thing as from a musical perspective. But what Rachel did not do was she didn’t add anything of her own, she shouldn’t add any notes that weren’t there. In the chords, in the harmony of the music and very very quickly after Rachel had done the two or three first song demos using a small computer I realized that that was something that she was already not doing. She was occasionally doing twiddly bits that I may like or not like but she never added, she never changed the chords. She went to great lengths to preserve the modality of the music. And then after that really I think I wanted her to have free reign and I think that right the way through the process Rachel would play me stuff and if there was anything that I particularly didn’t like, which was very rare, I would mention it and she would change it, literally right away on the computer.

We never really got into the kind of trouble that we might have got in if which if I had commissioned Rachel to do it and then come back and had an hour of music and a half to dissect and pick apart. It was done as we proceeded through the process. Martin Bachelor as her assistant took a couple of the base blockings that Rachel had done. She allowed Martin to or commissioned Martin as well to do orchestrations and his orchestrations are a little bit more romantic, I think that’s the right word, than Rachel’s orchestrations are but even there I felt that Martin was aware that, or maybe it was Rachel’s guidance of him.

People often say to me: ‘How do you play guitar to make you sound like Pete Townshend’. I remember some very very famous guitar player asking me that, that I was fans of and I said it is because I often only playing two notes. Very early on I realized that when you take two notes on a guitar and distorted it you’re actually producing three notes if not even four. There are sub harmonics by distortion. So my sound is very spare and my chord work is very spare and Rachel honored that and that was very important.

You’ve said I think, in the past, that Quadrophenia, The Who album, is the work you’re most proud of. Do you still feel that way and do you regard this as sort of a parallel; that this should be taken together now?

I think with respect for my work with The Who I do feel that it is the best work at least the best constructed, for me as a composer. Whether or not it is the best Who album is another story but it is one of my favorites because I produced it. I had complete control of it as I said earlier. You know, The Who didn’t do so many records compared to some other artists and had a long period of down time in the middle of our career, so Quadrophenia for me does stick out and it sticks out. It is the most mine, I think. It feels like it is the most mine of all Who records. Therefore this new version of it, this new interpretation of it, this new rendition of it, this new performance of it, reading of it, feels like something that I can do and that I am enjoying doing and I think it will hopefully bring what I feel is my best composition to a new audience perhaps. Who knows…